Bringing Thangkas back to life

The local women in Ladakh are the first to restore centuries-old Tibetan Buddhist paintings

Restoring Thangkas—paintings on silk appliqué or cotton that usually depict a Buddhist deity—is not for the fainthearted. “If there is even a minor mistake in restoration, like if the shape of an ear gets a little twisted [and different] from what it originally looked like, people might take offence,” says Dorjay Angchok, a resident of Matho village. “It is a sensitive job.”

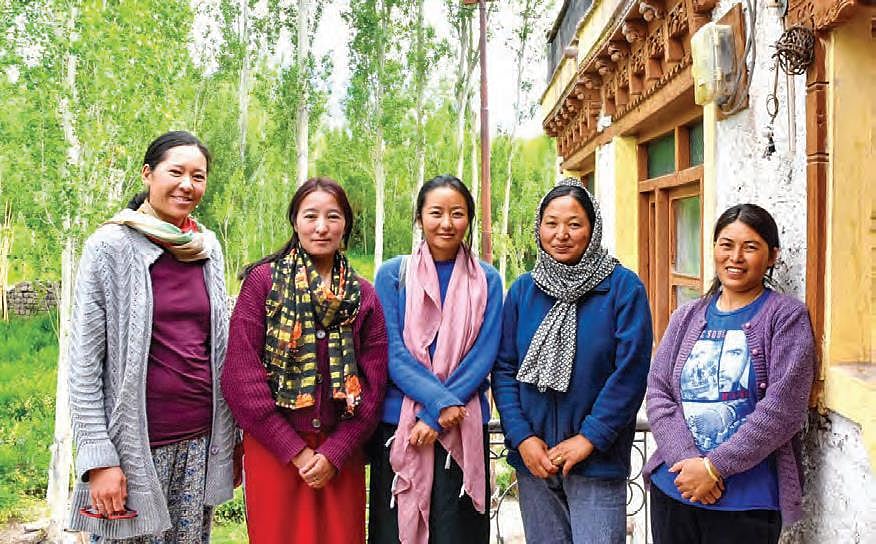

Located 26 kilometres from Leh, with a population of 1,165 people (Census 2011), Matho is almost entirely Buddhist. The fears of Angchok and others from her community have been put to rest by a team of nine skilled Thangka restorers who have travelled back in time to understand, recognise and discern the centuries-old painting patterns locked in these ancient works of art. Each century had its own elements, style and iconography.

The Thangkas that these women from Matho restore are all from the 15–18th century, says Nelly Rieuf, an art restoration expert from France who trained the women. “Thangkas are difficult to restore compared to other historical paintings since the silk cloth is rare and of extremely pure quality. Dissolving the dirt without harming the paint or the cloth is tricky,” says Nelly.

“Initially, the villagers were against women restoring Thangkas," says Tsering Spaldon. “But we knew that we were doing nothing wrong; we were doing something for our history”.

Buddhist nun Thukchey Dolma, from the Karsha nunnery in the remote Zanskar tehsil of Kargil district in the newly designated Union Territory of Ladakh says, “Thangkas are efficient teaching tools about the life of the Buddha and various other influential lamas and bodhisattvas.”

Tsering and other restorers, who are from farming families, are part of an organisation called the Himalayan Art Preservers (HAP). “We started learning preservation work at the Matho gompa [monastery] in 2010. It was better than sitting idle after finishing Class 10,” says Tsering.

That was the year the Matho Monastery Museum helped catalyse hope for the damaged Thangkas. “There was an urgent need to restore the Thangkas and other artefacts of religious significance. We started learning about this restoration work,” says Tsering. Joining her was Thinles Angmo, Urgain Chodol, Stanzin Ladol, Kunzang Angmo, Rinchen Dolma, Ishey Dolma, Stanzin Angmo and Chunzin Angmo.

They were offered Rs. 270 rupees a day. “A significant amount, especially considering our remote location and limited job opportunities,” says Tsering, adding that over time, “we realised the relevance of restoring these paintings. Then we started to appreciate art and history even more.”

The time taken to repair a Thangka depends on its size. It varies from a few days to a few months. I learn that “Thangka restoration rokna padta hai sardiyon mein kyuki fabric thand mein kharab ho jata hai [We stop the Thangka restoration work during the winters because the fabric gets spoiled in the cold].”

Stanzin Ladol opens a large register with work samples carefully catalogued. Two images are placed side by side on each page—one before restoration and the other showing the improvement afterwards.

“We are very happy we learned how to do this work; it has given us a different career to pursue,” says Thinles as she chops vegetables for dinner.

“All of us are married, we have children doing their [own] thing, so we spend a good amount of time occupied with restoration work. We wake up at 5 a.m. and try to finish all our housework and farm work.” Her colleague Tsering chimes in to say, “Kheti bahot zaroori hai, self-sufficient rehne ke liye [Farming is very important for us to stay self-sufficient].”

It’s a long day for the women. “We milk the cows, cook, send our kids to school, then we have to keep an eye on the cattle that have gone out to graze. After all this, we come to HAP and start work,” says Thinles.

A growing concern is the lack of restoration material, which is expensive, says Stanzin Ladol, adding, “This work is important to us not because we make a big profit out of it, but because by doing this, we get satisfaction.”

The restorers say that almost all funds go towards making new Thangkas. “Hardly any people nowadays understand the heritage value of these centuries-old Thangkas, and discard them instead of restoring them,” says Dr Sonam Wangchok, a Buddhist scholar, and founder of the Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation, based in Leh.

“Nobody says anything to us anymore because many years have passed and we have been doing it regularly,” says Tsering, speaking briefly about the initial resistance they met from people in the village. Noor Jahan, founder of Shesrig Ladakh, an art conservation atelier based in Leh, points out, “Hardly any men take up this job.

It is mostly women who are art restorers here in Ladakh.” And their work is not limited to the restoration of Thangkas—they have also moved into the restoration of monuments and wall paintings.

“We want more people to come here and see our work,” says Tsering. The sun is going down in the mountains, soon it will be time for them to go home. The job has given these women much more than the skill to restore these ancient paintings, it has equipped them with confidence.

“It has also gradually changed how we communicate—earlier, we would only speak in Ladakhi,” says Tsering with a smile. “But now we are also learning to be more fluent in English and Hindi.”

[Avidha Raha is a photojournalist interested in gender, history and sustainable ecologies. Courtesy: People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)]

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines