Remembering Mir Taqi Mir, the Lord of Poetry, 215 years later

Mirza Ghalib overtook him in the popularity stakes, but Khuda-e-Sukhan came first — and many scholars consider him the greater poet, not just prior

Hasti apni habab ki si hai

My life is like a bubble, this world is like a mirage

On 20 September 1810, in the cultural heart of Lucknow, one of Urdu’s greatest voices fell silent. Yet, more than two centuries later, Mir Muhammad Taqi — better known to the world as Mir Taqi Mir — continues to breathe in the cadence of every ghazal, in the sigh of every verse, and in the melancholy of every lover who finds language too inadequate to his heartbreak.

Called Khuda-e-Sukhan (the lord of poetry), Mir’s genius was not simply in ornamenting the emerging language of Urdu; he gave it its soul. His words carried a universality of emotion, weaving love, loss, longing and metaphysical despair into verse so elemental that they seem to speak across centuries.

Dikhaai diye yun ki bekhud kiya

She appeared in such a way that I lost myself…

Mir was born on 28 May 1723 in Agra, into a family steeped in spirituality and learning. His father’s mystical leanings profoundly influenced him, shaping his poetic sensibility towards compassion, detachment and the inner world of love.

Orphaned early, Mir wandered to Delhi at the tender age of 11, where the city — then the cultural nerve centre of poetry and power — would leave an indelible imprint on him.

The Delhi of Mir’s youth was a paradox: dazzling in refinement, yet ravaged by repeated invasions. The sackings by Ahmad Shah Abdali from 1748 onward left the city bruised, its poets and courtiers disillusioned. Mir’s verses absorbed that collective trauma, mourning Delhi’s decline even as he immortalised its ethos.

When the city’s glory dimmed, Mir accepted the invitation of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula of Awadh and shifted to Lucknow. There, amidst Lucknow’s indulgent aesthetic of nafasat (refinement) and naazuk mizaj (delicate sensibility), Mir remained a misfit — carrying Delhi’s ruins in his heart.

Mir dariya hai, sune she’r zabaani uski

Mir is a river, hear his verses, and marvel at their flow!

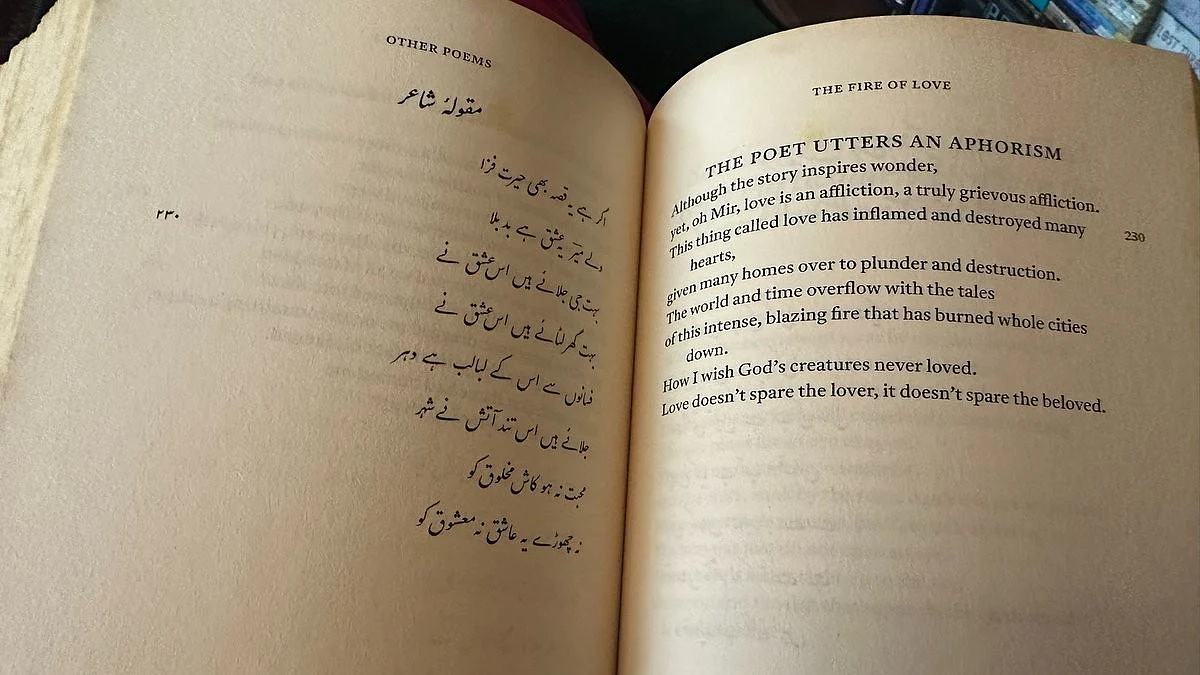

Mir’s legacy is monumental. His Kulliyat (Collected Works) spans six diwans, holding 13,585 couplets across genres: ghazals, masnavis, qasidas, rubaiyat, satires. But it is the ghazal where Mir reigns supreme.

His ghazals marry simplicity with profundity, carrying such intimacy that the reader feels addressed personally. His celebrated masnavi ‘Mu’amlat-e-Ishq (the Stages of Love)’ remains one of Urdu’s finest explorations of love’s ecstasies and devastations. His Zikr-e-Mir, an autobiography in Persian, reveals a man wounded deeply by fate, yet resilient enough to transmute anguish into verse. His Nukat-us-Shu‘ara, a pioneering biographical dictionary of poets, also reflects his keen awareness of literary tradition.

Mir did not invent Urdu poetry, but he gave it maturity, depth, and musicality. By fusing Hindustani idiom with Persian imagery, he birthed Rekhta — the supple form of Urdu that became the chosen medium for later giants like Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz.

Ashk aankhon mein kab nahin aata?

When does the tear not rise in my eyes?

Sorrow was Mir’s constant companion. He endured the deaths of close family members, the plunder of Delhi, the betrayal of friends, and the neglect of patrons. These wounds etched themselves into his poetry, earning him the reputation of the poet of pathos, of grief made eternal.

One cannot read Mir without feeling the press of melancholy: “Deedani hai shikastagi dil ki / Kya imaarat ghamon ne dhaai hai (Worth watching is my heart’s ruin; what a citadel sorrows have razed)”.

Yet, his sadness was never mere lament. It was transmuted into art, achieving that rare alchemy where private suffering acquires universal resonance.

Raah-e-door-e-ishq mein rootaa hai kyaa

On the long road of love, why do you wail?

At the core of Mir’s poetry lies love — not just the romantic pursuit of the beloved, but love as a philosophical, almost spiritual force. His verse captures both its intoxication and its inevitable wounds: “Bekhudi le gayi kahaan humko / Der se intezaar hai apna (Where has selflessness taken me? I’ve been waiting for myself for long)”.

Unlike Ghalib, who intellectualised love into abstraction, Mir made it visceral — concrete, earthy, throbbing with pain and ecstasy. His beloved is not a distant metaphor but a palpable presence whose absence burns like fire.

Mir ke deen-o-mazhab ka poonchte kyaa ho?

Why ask of Mir’s faith or belief?

Mir transcended the narrow boundaries of creed and orthodoxy. In a famous couplet, he declared: “Mir ke deen-o-mazhab ka poonchte kya ho un nay to / Kashka khaincha dair mein baitha, kab ka tark Islam kiya.”

To Mir, love itself was the highest faith. His verses inhabit both mosque and temple, both tavern and shrine, without contradiction. This fluidity not only defied dogma but also forged a language of pluralism — a quality that keeps his voice startlingly relevant in a fractured world.

Rekhta ke tum hi ustaad nahin ho, Ghalib

You are not the only master of Rekhta, Ghalib…

The question often posed — who is greater: Mir or Ghalib? — has never found a final answer. Even Mirza Ghalib himself acknowledged Mir’s genius, humbly reminding his admirers that “they say there used to be a Mir in the past”.

The literary critic Shamsur Rahman Faruqi has argued that Mir’s range, his ability to create mood along with meaning, gave him a stature even beyond Ghalib. If Ghalib was the mind of Urdu poetry, Mir was its heart. One abstract, the other earthy — together they embody Urdu’s richest inheritance.

Baad marne ke meri qabr pe aaya wo ‘Mir’

After I died, he came to my grave…

Mir’s end was as tragic as much of his poetry. Living in Lucknow, alien to its culture of excess, he remained melancholic and solitary. In 1810, an overdose of medicine claimed his life. He was buried quietly, with little of the grandeur his genius deserved.

Yet, his afterlife in poetry has been nothing short of monumental. Scholars like C.M. Naim, Ralph Russell, Frances Pritchett and Shamsur Rahman Faruqi have ensured his poetry remains studied and celebrated.

For readers, his verses remain balm and wound alike.

Ibtidaa-e-ishq hai, rootaa hai kyaa?

’Tis only just begun, this love, so why do you weep?

Now, 215 years after his passing, Mir Taqi Mir is still no relic of literary history. He is a living pulse.

His couplets echo in mushairas, his verses are sung in ghazals, his lines shared in quiet texts between lovers and friends. In every broken heart, in every sigh of love, in every seeker’s restlessness... Mir remains.

His ghazals remind us that even amidst ruin, there is beauty; that even in loss, there is art; that language, when touched by true genius, becomes eternal.

Patta patta boota boota haal hamaara jaane hai

Epilogue: Khuda-e-Sukhan

“Patta patta boota boota haal hamaara jaane hai, Jaane na jaane gul hi na jaane, bagh to saara jaane hai [Every leaf, every blade of grass knows Mir’s sorrow. The world knows. Only the beloved remains oblivious].”

That is Mir’s tragedy, and our gift — for from that neglect was born poetry that transcends time.

On this day, as we remember Mir Taqi Mir, we do not just mourn a poet who died in Lucknow in 1810.

We celebrate a voice that will never die, because as long as hearts love, break and yearn, Mir will always be read, recited and revered.

Views are personal

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines