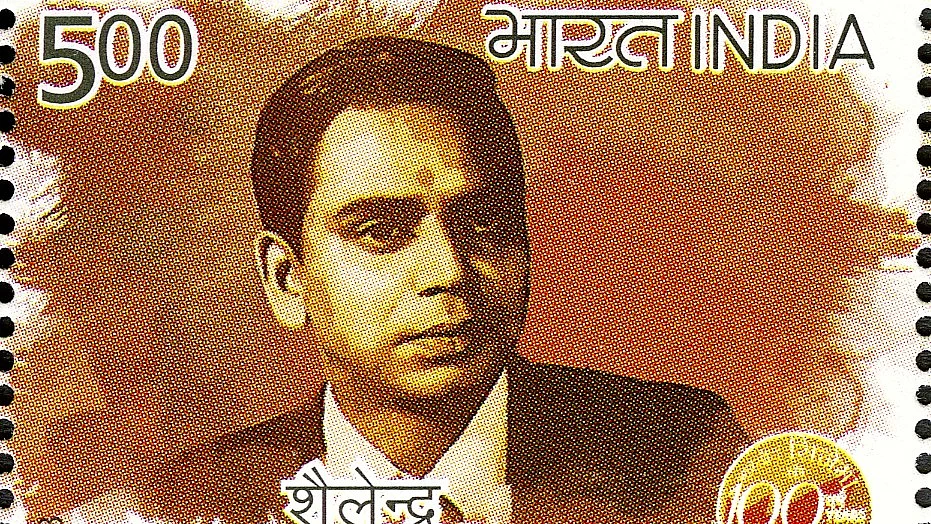

Shailendra: Raj Kapoor’s ‘Pushkin’ and Hindi cinema’s poet of the people

On his 102nd birth anniversary, remembering Shankardas Kesarilal Shailendra, whose verses gave Indian cinema some of its most immortal songs

In the grand history of Indian cinema, few names shine as luminously as that of Shankardas Kesarilal ‘Shailendra’ (30 August 1923–14 December 1966). To millions, he was simply Shailendra, the poet whose pen gave Hindi films their soul, their humanity, and their timeless melodies.

To Raj Kapoor, he was more — confidant, comrade, and muse — fondly christened as ‘Kaviraj’ and ‘Pushkin’, likening him to the great Russian poet. If Sahir Ludhianvi embodied fire and protest, and Kaifi Azmi wrote with the conviction of revolution, then Shailendra was the lyricist of everyman’s joys and sorrows — his words simple, direct, but touched with infinite depth.

In his songs, the Indian public found its voice: the laughter of love, the ache of loss, the certainty of struggle, and the quiet courage to live.

From Mathura’s by-lanes to Bombay’s dreams

Born in Rawalpindi and raised in Mathura, Shailendra belonged to no literary elite. His early life was marked by poverty and struggle, and his foray into verse came not from salons of privilege but the restlessness of a working-class heart.

After moving to Mumbai, he worked as an apprentice in the Matunga Railway Workshop in 1947. Poetry was his release, and at mushairas (poetry gatherings), his fiery verses — like 'Jalta hai Punjab' — attracted attention.

Among those who noticed was Raj Kapoor, who first approached Shailendra to buy his poem for his debut film Aag (1948). The idealistic young poet, then associated with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), declined, wary of commercial cinema. But fate soon intervened. With his wife pregnant and money scarce, Shailendra approached Kapoor himself. Kapoor gave him two pending songs in Barsaat (1949) to write.

For Rs 500, Shailendra wrote 'Patli kamar hai' and 'Barsaat mein humse mile tum'. With Shankar-Jaikishan’s compositions and Kapoor’s charisma, the songs clicked — and with them, a lifelong bond was born.

The Raj Kapoor–Shailendra–Shankar-Jaikishan trinity

From that point on, the holy trinity of Raj Kapoor, Shailendra, and Shankar-Jaikishan defined Hindi cinema’s golden musical era. Kapoor’s cinematic canvas, Shankar-Jaikishan’s sweeping music, and Shailendra’s evocative words created songs that resonated across continents.

Who can forget 'Awara hoon' from Awara (1951)? The anthem of the vagabond became not only a symbol of post-Independence Indian angst but also a cultural bridge — echoing from Moscow to Cairo, turning Raj Kapoor into an international icon. Similarly, 'Mera joota hai Japani' from Shree 420 (1955) distilled the contradictions of a young nation — clothed in borrowed modernity but carrying an unmistakably Indian heart.

Shailendra’s gift lay in simplicity with profundity. His words were never ornate, but always human and real. When Mukesh sang 'Dost dost na raha, pyaar pyaar na raha' in Sangam (1964), it was not just a filmi lament but an articulation of life’s inevitable betrayals. When Lata Mangeshkar sang 'Aaja re, main to kab se khadi is paar' in Madhumati (1958), it was longing in its purest, aching form.

Beyond Raj Kapoor: The versatile collaborator

Though forever linked with Raj Kapoor, Shailendra’s brilliance extended far beyond. With Bimal Roy, he created gems like 'Dharti kahe pukar ke' (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) and the hauntingly beautiful Madhumati (1958), including 'Suhana safar aur yeh mausam haseen' and 'Dil tadap tadap ke keh raha hai'.

With S.D. Burman and Dev Anand, he penned the masterpieces of Guide (1965) — songs that remain philosophical milestones of Hindi cinema: 'Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai', 'Din dhal jaaye, haaye raat na jaye', 'Tere mere sapne ab ek rang hain'.

With Salil Chowdhury, he touched transcendence in Bandini (1963) with 'Mora gora ang lai le' and 'O jaanewale ho sake to laut ke aana'. With Ravi Shankar in Anuradha (1960), he showed his lyrical adaptability.

Each collaboration proved that Shailendra was not merely a lyricist for a star or a composer — he was a poet for cinema itself.

The story behind a song

A lesser-known anecdote captures Shailendra’s genius and wit. When disappointed that Shankar-Jaikishan failed to recommend him to producers as promised, he penned a note saying: 'Chhoti si yeh duniya, pehchaane raaste hain; kahin toh miloge, toh poochhenge haal.'

The duo instantly recognised his subtle reproach, apologised, and later set those very lines to music in Rangoli (1962). Shailendra’s pen was thus both sword and balm — gentle, but unignorable.

The tragedy of Teesri Kasam

Shailendra’s poetic heart sought expression beyond lyrics. He ventured into film production with Teesri Kasam (1966), based on Phanishwar Nath Renu’s short story, starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman, directed by Basu Bhattacharya.

Artistically, the film was a triumph, winning the National Award for Best Feature Film, but commercially it failed. Shailendra, already burdened by financial strain, was devastated. His health declined, worsened by anxiety and alcohol. On 14 December 1966, at just 43, the poet who gave our cinema some of its most immortal songs, passed away. Ironically, the film that hastened his end is today regarded as a classic of Indian parallel cinema.

Legacy that refuses to fade

Though Shailendra lived briefly, his songs remain timeless. Gulzar, himself a master poet, has often said: “Shailendra was the finest lyricist Hindi cinema has ever produced.”

His work won him three Filmfare Awards for Best Lyricist — for 'Yeh mera deewanapan hai' (Yahudi), 'Sab kuch seekha humne' (Anari), and posthumously for 'Main gaaoon tum so jao' (Brahmachari).

Even after his death, his legacy continued. His unfinished song 'Jeena yahan, marna yahan' for Mera Naam Joker (1970) was completed by his son Shaily Shailendra — fittingly, it became Raj Kapoor’s swansong anthem, encapsulating both Kapoor’s cinema and Shailendra’s life philosophy: life begins and ends here, in the embrace of art and humanity.

Why Shailendra still matters

In today’s Bollywood, where lyrics often fade into the background noise of beats, Shailendra’s work is a reminder of a time when words were as integral as melody, when songs were literature sung aloud. He spoke to India’s aspirations, sorrows, and moral dilemmas in language every rickshaw-wallah and professor could understand.

Songs like 'Nanhe munne bachhe teri mutthi mein kya hai' (Boot Polish) carried the optimism of Nehruvian India. Others like 'Duniya banane wale, kya tere mann mein samai' (Teesri Kasam) dared question existence itself. This rare spectrum — from lullaby to manifesto — was Shailendra’s gift.

As we mark his 102nd birth anniversary, Shailendra is not just remembered as a lyricist but as Bollywood’s poet laureate. Raj Kapoor’s affectionate title — Pushkin, the Kaviraj — was not hyperbole. Like Pushkin, Shailendra democratised poetry, bringing it from the high pedestals of academia to the lips of common people.

His songs were not written for stars or filmmakers; they were written for the Indian people, who continue to hum them decades later. Shailendra may have left this world young, but his verses ensure he never really left. To borrow his own immortal words: 'Jeena yahan, marna yahan, iske siwa jaana kahan?'

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines