Is the Spirit Gendered?

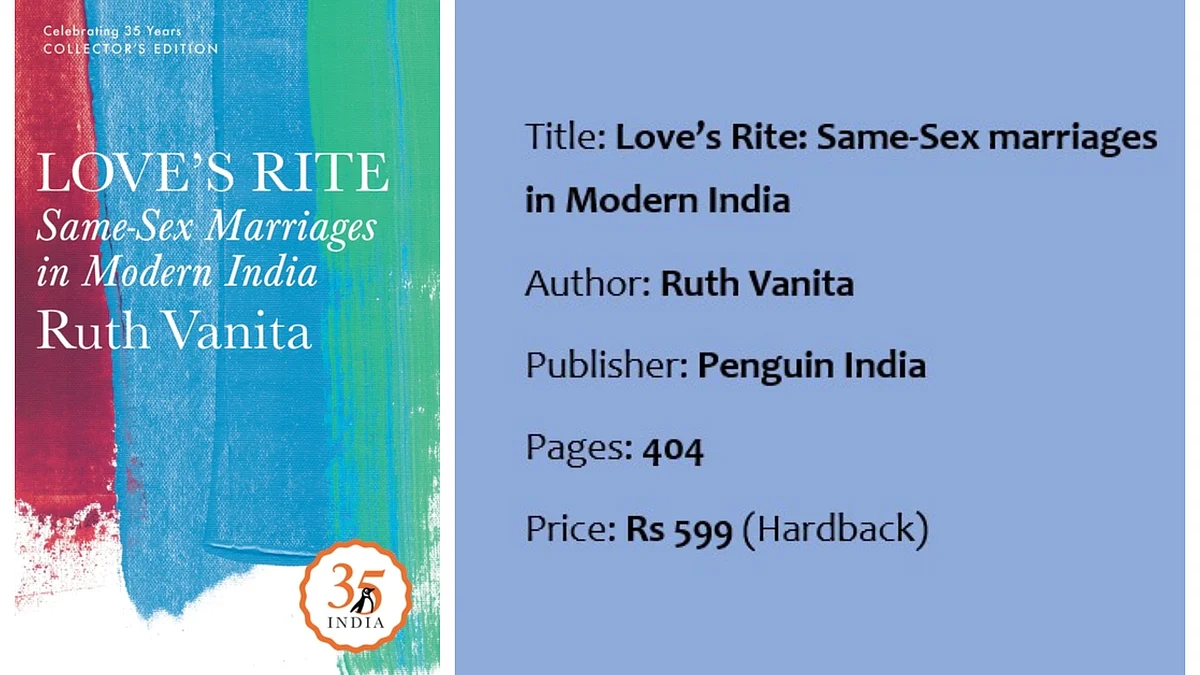

Excerpts from a luminous work of scholarship on the same-sex marriage debate by Ruth Vanita, a teacher and founding co-editor of 'Manushi'

The Wise One, who sees the same everywhere, sees no difference between happiness and sorrow, man and woman, fortune and misfortune.

–Ashtavakra Gita, XVII: 15

After all, what is marriage? It is a wedding of two souls. Where in the scriptures is it said that it has to be between a man and a woman?

–Sushila Bhawasar, a village school teacher, commenting on the marriage of her neighbours, policewomen Leela and Urmila

Many people would accept Sushila’s view of marriage as a union of two souls. However, not all would agree with her logical conclusion that since the soul is not gendered, a marriage between two men or two women is permissible.

In this chapter, I discuss the implications of the soul’s genderlessness for the possibility of same-sex marriage, and examine some traditional ideas of human-divine same-sex marriage. While these concepts refer to levels of reality beyond day-to-day embodiment, I argue that they are available to people who respond to the present-day phenomenon of same-sex marriage.

In Hinduism, as in Christianity and Islam, gender is often perceived simultaneously as very powerful and as irrelevant. This paradox makes possible the enforcement of gendered social roles along with the perception of spiritual non-difference.

Thus, although St. Paul declares that in Christ there is ‘neither male nor female’, he assigns different roles to women and men. How does this paradoxical understanding of gender affect an understanding of same-sex unions on the spiritual and social planes?

Original wholeness

In the Symposium, Plato’s fifth-century BC dialogue on love, Aristophanes recounts a myth about the origins of gender and sexual desire. He says that originally all human beings were of three sexes—male, female, and male-female or hermaphroditic. Each of these original beings was round. It had two faces, one in front, one at the back, and two sets of genitals. It also had four legs and four arms.

Aristophanes describes these original beings not as monstrosities but as stronger and more complete than present-day humans: ‘Terrible was their might and strength, and the thoughts of their hearts were great’. When they challenged the Gods to combat, Zeus decided to reduce their strength by cutting each one in half. Thus originated human beings with one face, one set of genitals, two arms and two legs.

Erotic love, Aristophanes says, is our search for our original other halves. Those men who were originally part of a round, all-male being, desire other men. Those women who were originally part of a round, all-female being, desire other women. But those who were originally parts of round, hermaphroditic (male-female) beings desire the opposite sex.

Aristophanes thus explains heterosexual and homosexual desire as originating in the same way, from human desire for an original state of wholeness. Same-sex desire is linked to being all-male or all-female, and cross-sex desire to androgyny. This is the opposite of modern stereotypes of homosexual men as effeminate, lesbians as masculine, heterosexual men as manly and heterosexual women as feminine.

Western commentators have generally viewed this remarkable narrative as anomalous, and even dismissed it as farce because comic dramatist Aristophanes narrates it. However, comparing it to stories in ancient Hindu texts reveals similarities that suggest a possible common Indo-European source for some elements of the narrative—original roundness and power; the creator's reduction of this power by splitting the round beings; original androgyny splitting into maleness and femaleness.

In the Kurma Purana, the creator God Brahma produces Rudra, who is ‘half-male and half-female and was too terrible to behold. “Divide yourself,” saying this, Brahma vanished out of fear’. Rudra splits into a male and a female. The male is Shiva and the female Parvati, who is then born as the daughter of the king of mountains. She longs to unite with her original other half, Shiva.

At her father’s request, Parvati reveals herself in her divine form: ‘It had hands and feet all round, had eyes, heads and faces in all directions’. On seeing this form, her father is ‘frightened and struck with awe’. He requests her to reveal another form, and she assumes a gentle female form with two eyes and arms. In this account, as in Plato’s narrative, original roundness and multiple limbs inspire terror in father Gods.

Gender resulting from a split

In Plato’s myth, one of the three types of original round beings is male-female. This type of being is absent from the creation story of Adam and Eve, accepted by Jews, Christians and Muslims. In Hinduism, there are many creation stories, and some incorporate ideas of androgyny and bisexuality.

Although Hindu gods and goddesses are male and female respectively, Hindus also think of every deity as simultaneously male and female, or neither male nor female. Thus, in the Kurma Purana, goddess Parvati tells her father that she is ‘non-different’ from Shiva. All the texts devoted to Goddesses stress this non-difference.

Shiva is often represented as half-male and half-female (ardhanarishwara). The common understanding of this icon is that Parvati is one with him and constitutes half of him. Here, as in Plato’s myth, heterosexual union is understood as congruent with androgyny. Both Plato’s myth and the Hindu texts associate heterosexual union with androgyny or the condition of being half-male, half-female.

Goddess texts show this androgyny originating from original all-female and all-male forms. Thus the Lalita Mahatmya, a goddess text embedded in the Brahmanda Purana, subordinates Shiva to an original female principle. It tells us that the male Shiva attained his androgynous form through devotion to the goddess: ‘By worshipping and propitiating her and also by means of the power of meditation and Yogic practice, Lord Siva became the leader of all Siddhas and also became the lord, half of whose body has the female Sakti form’.

Many-limbed beings

Plato’s narrative is one of very few texts in the Western canon that imagines an entity with more than two arms and two legs as a positive figure. Hindu Gods, Goddesses and other divine beings frequently have more limbs than humans—Brahma has four heads, Gayatri has five, and other deities are routinely represented with four or more arms.

This multiplicity of limbs is a sign of divine strength and versatility. In the Kurma Purana, the universe itself is many-limbed: ‘All round it (the universe) has hands and feet; it has eyes, heads and mouths on all sides; all round, it has ears; it exists enveloping the world’.

Apart from residual images like that of the six-winged holy beings ‘full of eyes before and behind’ in the Book of Revelation, Christian icons represent divine beings anthropocentrically as two-armed and two-legged. Yet, Christianity retains the older idea of circularity as perfection. The Christian wedding ring and the Hindu wedding garland inscribe this notion into marriage.

Dante imagines Paradise as a series of circles, and British poet Henry Vaughan (1622-1695), drawing on Ptolemaic cosmology, envisions eternity as circular: ‘I saw eternity the other night/ Like a great ring pure and endless light/ All calm as it was bright…'

(Excerpted with permission from Penguin Random House India)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines