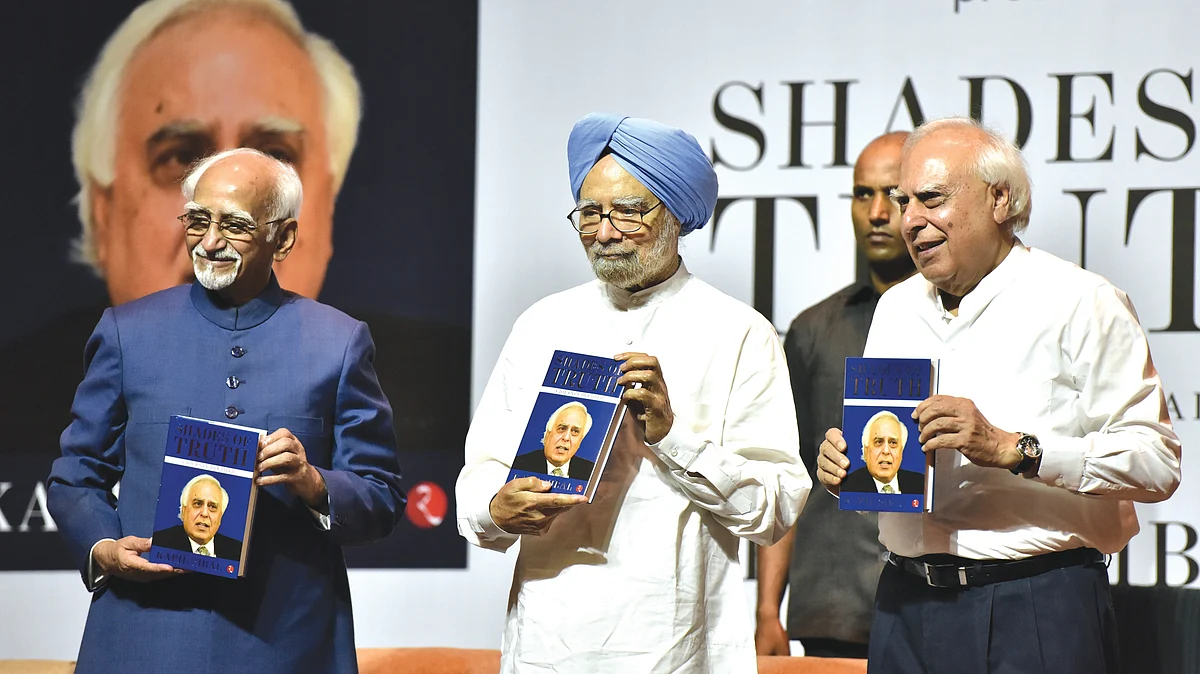

Kapil Sibal: The perilous wait for ‘Achhe Din’

The senior Congress leader’s book is a reality check for what Modi promised and delivered, and a lot more

Four years down the road, that dream has been shattered. The events that have unfolded during this period prove that Modi never meant what he promised. The much-debated issue of appointment of a Lokpal which would have ensured transparency in government, has still not seen the light of day. In 2011, the Lokpal Bill became a topic of conversation in almost every home in this country, especially amongst the middle class. This legislation was to empower ordinary citizens to complain against corrupt public servants and prosecute them. The BJP, then in Opposition, pushed for it. However, since Modi came to power, the issue has been put in cold storage. No Lokpal has been appointed ( The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act 2013 was passed by the Congress-led UPA government and notified on 1 January 2014). While hearing a petition led by an NGO on the delay in appointment of the Lokpal on 23 November 2016, the then Chief Justice of India, Justice T.S. Thakur, pulled up the Modi government and said, ‘We can’t allow a situation where a law or an institution like Lokpal becomes redundant.’ Modi realized that an institution like Lokpal would jeopardize the functioning of his own government. He charged the UPA government with corruption but now seeks to protect his own from any form of investigation on charges of corruption.

The Lokpal was a sword to strike at the UPA, castigated for its lack of resolve to combat corruption. However, multiple legislations have not helped eradicate this menace. The Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA) of 1988, which deals with public servants and provides procedures to bring them to book, has had no real impact on the prevailing endemic levels of corruption. In fact, there is a general perception, also shared by Members of Parliament (MPs), that if such sweeping powers as provided in the Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013, vest in investigating agencies, it might lead to a regime where those who are themselves perceived to be corrupt will be given the absolute authority to deal with corruption. The scandals that have recently emerged—and many more which may never see the light of day—have shown the investigating agencies to be guided by biased agendas and selective in dealing with corruption. Some of them holding the reins of power are, in fact, perceived to be protecting the corrupt. I suspect that before the end of the term of this government, if Modi perceives that he may lose power in 2019, he will be inclined to pass an amended Lokpal Bill.

As for black money, in the run-up to his campaign for prime ministership, the vulgar extravaganza displayed on television channels suggested that the BJP was flush with funds. Media planners placed the tab on Modi’s media campaign at Rs 5,000 crore. Any party with such enormous resources cannot possibly be serious about its commitment to eradicate black money. But most modern day politicians pay scant respect to principles. Double standards are the norm. In the February– March 2017 Assembly elections, soon after demonetization, enormous flow of funds was visible wherever the BJP campaigned. The legitimate earnings of ordinary folk were frozen during demonetization while the Uttar Pradesh election witnessed rampant use of cash.

‘There is no immediate prescription like instant Maggi noodles by which inflation can be brought down.’ This double standard is also reflected in Modi’s statements on this issue as Gujarat Chief Minister. He insisted that controlling inflation was the sole responsibility of the Centre and that its failure could not be passed on to state governments. However, after becoming the prime minister, he did an about-turn and said that it was the joint responsibility of the Centre and the states to curb inflation

After he became the prime minister, Modi not only failed but also completely forgot that he had promised to bring back black money stashed abroad. Nearly five months after assuming office, the government told the Supreme Court on 17 October 2014 that it could not reveal the names of Indians having accounts in foreign banks due to the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), a position that was earlier taken by the UPA. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley defended the government’s stand by saying, ‘Is the present NDA government led by Modi in any way reluctant to make some names public? Certainly not. But they can be made public only in accordance with the due process of law.’

This government now says that any such accounts opened after 2017 will be made public, pursuant to an agreement between India and foreign powers under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) on the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) portal. But why can’t the names of account holders prior to 2017 be revealed—a demand made on the floor of the Lok Sabha by the then BJP in Opposition? Sushma Swaraj, erstwhile Leader of the Opposition, in her spirited interventions, accused the UPA of protecting the corrupt despite the Finance Minister’s statement that the names could not be revealed. When the Congress reminded the BJP of the promise Modi had made, there was no response. Modi realized that his promise was only a ‘jumla’ meant to convince the public that the UPA was corrupt and protecting the corrupt.

Modi has failed miserably in his developmental agenda, which has bedevilled the Indian economy in the last four years with rising unemployment, lack of growth, a stagnant agricultural sector, inflation in essential commodities (especially food items), failure to protect the farmers and inability to give an impetus to manufacturing.

Addressing the deeper malaise

India’s exports had been robust during the tenure of the UPA; but falling exports are a drag on the growth story of the NDA. The average growth rate of exports during the 10 years of UPA rule (2004–14) stood at 18.1 per cent, while during the first three years of NDA rule (2014–17), the average growth rate was negative. Perhaps the reason was that export earnings were largely based on oil imports converted into petrochemicals and other plastic-based commodities. With the fall in the price of crude oil during 2015–16, the consequent price of crude-based products fell substantially. But the differential between the price of imported crude and the sale of petrol and diesel at the gas stations went into the kitty of the treasury with increased excise. The consumer did not benefit and exports suffered. We, of course, cannot lose sight of the fact that global slowdown also reduced global demand for consumer products. China’s rate of growth had come down from 10 per cent to a mere 6.5 per cent. The third element in declining exports was the appreciation of the rupee against the dollar.

Some experts attribute declining exports to a malaise deeper than the reasons set out above. The reality is that Indian merchandise exports are very narrow-based—we export low-value commodities such as cotton yarn or apparel rather than technical textiles. The poor logistics infrastructure along with a weak trade facilitation regime is also the cause of our poor performance. Our cost of logistics as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is anywhere between 13 and 14 per cent compared with 7 to 8 per cent in developed countries. Besides, India has failed to negotiate improved market access for the country’s exports. We face prohibitive tariff and non-tariff barriers in both developing and emerging markets. In Europe and other developed markets, Indian exports face non-tariff barriers. While we are somewhat generous in providing unilaterally, duty-free market access to Bangladesh and other countries, we do not get the same treatment from other nations. Japan is an example where, through the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), India’s pharmaceutical products have benefited from tariff reductions.

Another reason for our poor export performance is the high import duties we impose on raw materials and intermediates while keeping the duties on finished products low, which discourage production and export of value-added items. For instance, apparel can be imported duty-free but its raw material attracts a 10 per cent duty.

The NDA, in the last four years, has not focussed on the consistent decline of our exports. Of course, the saving grace is that exports of services have shown only a moderate decline. The NDA should have entered into trade pacts and persuaded nations to lower their tariffs, easing the flow of exports from India. Reducing cost of finance and logistics would have enabled exporters to be competitive in the global market.

If one compares the prices of essential food items on 1 January 2014 with those prevailing on 1 January 2017, the percentage of upward variation is between 3.37 per cent and 75 per cent. Pulses, tea, milk, sugar, mustard oil, vanaspati, salt, wheat, rice and atta all cost dearer today. And this is when the price of crude oil came down from $108 a barrel to $53 a barrel during the same period. Despite this global downward trend in crude oil prices, diesel was sold at ₹53.78 per litre in January 2014, as against ₹57.82 per litre three years later. Similarly, an LPG cylinder, which was subsidized, was sold at ₹414 on 1 January 2014 against ₹434.71 three years later. So, while the government got an enormous cushion because of the reduction in crude prices, the benefit was not passed on to the consumer.

Since the beginning of 2018, international crude oil prices have firmed up. As of June 2018, the price of the Indian crude basket was hovering around the $75 a barrel mark, still below the $100 a barrel average of the first five months of 2014. However, petrol and diesel prices have gone up exponentially and, as on 25 June 2018, they are being sold at ₹75.69 and ₹67.48, respectively, in Delhi.

In the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections in 2014, Modi attacked the Congress for the high rate of inflation during the UPA years. He assured that if the governments of Morarji Desai and Atal Bihari Vajpayee could arrest price rise, his government could do it too. However, after assuming power, when the inflation rate touched a five-month high in June 2014, the government changed tack. BJP spokesperson Siddharth Nath Singh maintained,

‘There is no immediate prescription like instant Maggi noodles by which inflation can be brought down.’ This double standard is also reflected in Modi’s statements on this issue as Gujarat Chief Minister. He insisted that controlling inflation was the sole responsibility of the Centre and that its failure could not be passed on to state governments. However, after becoming the prime minister, he did an about-turn and said that it was the joint responsibility of the Centre and the states to curb inflation.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines