A Cage with a View: Under-trial life in an Indian jail

Human rights lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj’s account of her time in Yerawada Jail is also a poignant lesson in keeping hope alive in the teeth of absurd injustice

The jottings that make up this book were my way of coping with incarceration. Some prisoners pray, some weep, some just put their heads down and work themselves weary. Some fight defiantly every inch of the way, some are inveterate grumblers, some spew gossip. Some read the newspaper from cover to cover, some shower love on children, some laugh at themselves and at others.

I watched through the bars, and I wrote.

These notes were written during the first half of my incarceration; that is, during my time in the Yerawada Women’s Jail, Pune, between early November 2018 and late February 2020. I wrote them in my cell at night, in notebooks that I bought from the jail canteen. And when I was shifted to Byculla Jail, Mumbai, I took them with me. I typed them out after my release on bail in December 2021.

Except for the first week, I spent my entire time at Yerawada in the Phansi Yard (cells for death row convicts) of the women’s jail, where my co-accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, Professor Shoma Sen, and I were lodged in neighbouring single cells. We were never told why we were in this high-security unit for death-row prisoners, but it probably had something to do with our being arrested under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

I could take ten paces down the length of my cell and six paces across its width, and indeed I did a lot of pacing about. Our neighbours in the Yard were two highly strung sisters, lodged in similar separate cells, who had by then entered their twenty-fourth year in jail, of which nearly two decades had been spent on death row.

These four cells and a fifth vacant cell (used as a storeroom and bathroom by the Constables guarding us 24x7), and the narrow corridor into which they opened, were all enclosed in a cage-like structure, with bars all along the front. The cage lay along half the longer side of a rectangular grassy ground, overlooking it.

The other half of that side, to our left, was taken up by the Hospital Barrack. Barracks 1 and 2, housing mostly convicts, stood on the adjacent (shorter) side of the rectangle, to our right, and their windows overlooked the ground too.

Ours was a cage with a view. Through its bars we could see the sparse, well-worn lawn where women prisoners ate their lunch and played with their children, and could hear the sermons delivered by the visiting Brahma Kumaris (preachers from a spiritual organisation) on the raised cement Stage right in front of our cage.

We could observe the goings-on at the far end of the ground, such as women at the prison Gate leaving for courts or for the hospital, lining up at the Dispensary or waiting to enter the Mulakat (meeting) Room to meet their visitors.

We could watch the older children playing on the see-saw, swings and slide, and see women crossing over from our ‘Convict Compound’ to the adjoining ‘Undertrial Compound’. (These were not tightly sealed categories. There were undertrials—like us—in the Convict Compound, and the other way around.) The two compounds were separated by a high wall and a massive iron-sheeted gate towards the far end of the ground on the left.

[…]

We were not supposed to interact with other prisoners. In fact, Professor Sen and I usually spent sixteen and a half out of twenty-four hours in our adjoining individual cells. The wall separating us had a small window near the roof so one could shout to each other in an emergency.

For a few hours each day, we were let out into the narrow corridor outside our cells. In the winter we were let out of our cage for half an hour between 12 noon and 12.30 to ‘take the sun’, and later on this practice continued. This was a time when no other prisoners were out and about since everyone was locked up their barracks between 12 noon and 3 p.m.

So, how and when did I learn the stories of other women? When we huddled together in the police van en route to court, or spent hours cooped up in the paan-stained court lock-up waiting to be summoned to our respective courts. When we queued up outside the Mulakat Room, each anxious to meet her family and lawyers.

When we lined up outside the Dispensary and commiserated over each other’s aches and pains, or waited outside the Canteen to get our supplies for the fortnight. When we jostled at the common tap to fill bottles of drinking water and buckets for bathing and for washing clothes, under the eagle eye of our Constable on guard.

When we heard our Constable on duty chit-chat with other passing prisoners or a colleague. Sometimes our neighbours, the two sisters, would tell us stories too, when they were in a rare, pleasant mood. And there was no way we could be deaf to the fights in Barracks 1 or 2 or in the Hospital Barrack—the loud sounds of crying or cursing inevitably spilled out into the corridors and the ground.

[…]

[My] notes have no dates and no particular chronology. There are no dates also because jail life is like a grindstone, just turning and turning, with an unchanging routine. The passage of time is measured only by the changes of season and festivals. Besides, I had told myself that I should not expect to be released soon. I wanted to protect myself from the emotional rollercoaster of hope and despair every time a bail application was filed and rejected.

My prison notes are impressionistic snapshots, true to the moment, with no claim to being complete histories. I have omitted names to protect the privacy of these prisoners and avoid prejudice to their cases. Observing women, listening to them, writing about them, and about life in a women’s jail, helped me. This became my work. It gave me a sense of purpose. It calmed me. It helped me understand where I was and didn’t leave any scope for self-pity!

As a trade unionist for more than three decades and a human rights lawyer for nearly two, it is not as if I was unaware of the injustices prisoners were subjected to, and their sufferings.

I knew many laws were unreasonable, even draconian. I knew that the quality of legal aid was poor. I knew that the actions of courts were often prejudiced against the poor, the Dalits and the minorities. I knew that courts looked at crimes within the family through a patriarchal lens. But being in prison made one understand the enormity of it all, the serious implications of these things on real human lives. And above all, the urgency for reform.

This is not to say that all the women were ‘innocent’ or had not committed crimes. I did find, though, when I heard their stories, that a good number seemed to have been lured or forced or provoked into such crimes by their circumstances. In a more enlightened society than ours, the attitude towards crime would not be one of revenge or punishment, but of reform and rehabilitation.

So I have, in my sketches of them, tried to treat these women not as criminals but as human beings. I remember once in Byculla, when I was asked to sing—and I have a very loud singing voice—I sang ‘Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi’ (Someday, that morning will dawn), written by the poet Sahir Ludhianvi and sung in a Hindi film. When I came to the lines, 'Jailon ke bina is duniya ki, sarkar chalayi jayegi’ (One day the world will be governed without jails), not a single eye was dry.

---

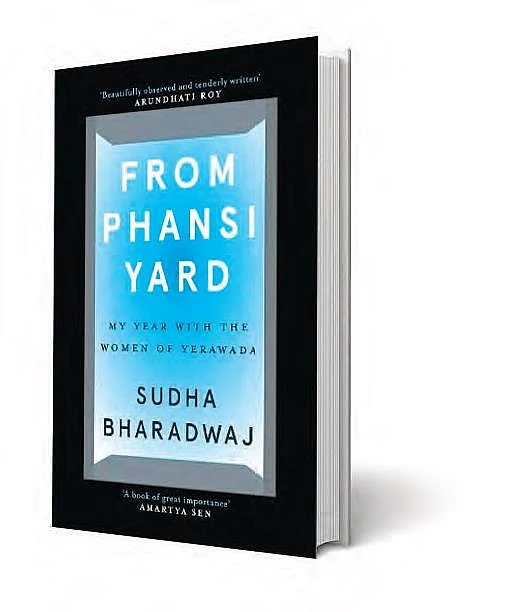

Title: From Phansi Yard: My Year with the Women of Yerawada

Author: Sudha Bharadwaj

Publisher: Juggernaut

Pages: 212 pp

Price: Rs 799 (hardcover)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines