Indian philosophy beyond Vedanta: Meet the Charvakas, the realists and sceptics

BJP/RSS are keen to project Advaita Vedanta as the only version of Hinduism. But Charvakas held Vedic rituals couldn't deliver Moksha, that the world isn't an illusion but real, writes Sonali Ranade

"I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark”

- Stephen Hawking

The Holy Grail of all six Schools of Hindu Philosophy is the idea of liberation [Moksha] from the eternal cycle of birth and death. But here is Stephen Hawking saying that nothing survives death. You are liberated from the cycle of death and reincarnations once the lights are switched off in your brain. Liberation is yours by default.

Now that’s a very radical idea.

However, the Charvakas, the real philosophers of ancient India, said the very same thing at the beginning of the Common Era, in their foundational text called the Charvaka Sutra, written by a Sage called Brihaspati.

Nothing survives death, said Brihaspati. The endless cycle of reincarnation is a priestly invention. In reality, it doesn’t exist. No wonder the priesthood of every tradition, [including the Buddhists and the Jains, who themselves preached there is no self,] rose as one to try and stamp out the Charvakas.

Why then do religions such as Hinduism, [but also Jainism and Buddhism,] make such a big deal out of the idea of liberation?

Redemption & Reincarnation: Friedrich Nietzsche explains how the concept of redemption was sold to Christians. Before you can sell people the idea of redemption through religion, you have to convince them of the need for it.

The Church achieved this by simply postulating that we are all born in sin - literally and figuratively - and are thus fallen people, who need to seek God, to make amends for a multitude of sins, in order to be readmitted to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Once you are convinced you are a sinner - and who hasn’t sinned? - you need religion, the church, its priesthood and all that comes with it, as you desperately seek the promised redemption.

At one level, it is a good way to order and organise a society. The system works to the extent that you can sustain faith in such an arrangement. The device has served vast swathes of humanity as a way to order society, with varying degrees of success, over thousands of years.

The corresponding idea in Indian traditions is the concept of reincarnation. We don’t know how the idea arose. The concept finds mention in the earliest of our texts such as the Vedas, and later in the Upanishads. The truth of it is assumed as a matter of fact.

Reincarnation involves cycling through all kinds of life-forms, from insects to snakes, from cows to cats. The horror of such an imagined experience is enough to send all of us scurrying to find Moksha. This clamour for liberation not only provides the priesthood with a living, and control over a community, but also helps produce an orderly society, especially, when used in tandem with the theory of Karma.

The theory of reincarnation presupposes a self, atman or Brahman that lives on even after your death, accumulating good or bad karma, in every life-form you cycle through. Liberation occurs when the good karma so overwhelms the bad, that you become eligible for liberation by reverting to the universal Brahman forever. [But why you get separated from the universal Brahman to be born in this world, is an issue our philosophy has never addressed. But it is an issue fraught with interest. A future Charvaka might use it as the starting point of a new philosophy.]

How does one accumulate good karma?

Back in the good old days, circa 1000 BCE, before the Great Forest and the Chandogya Upanishads, this process was rather straight forward.

If your Brahman wanted wealth or a large healthy and happy family or even Moksha, you consulted your priest, and he consulted the Vedas, to select an appropriate ritual sacrifice for you to make. This could involve anything - from goats to cows to gold coins.

Once the sacrifice had been made via the prescribed rituals, you could rest in peace and wait for the desired outcome. It was as simple as that.

The problem with these Vedic rituals was that they often didn’t produce the desired results; which brought the authority of Vedas, and the priests, into question. As these doubts grew, there arose the Jains, Buddhists, and some Vedic people like the Charvakas, who questioned the Vedic theories of self/atman, and the efficacy of Vedic rituals, in achieving Moksha or anything else for that matter.

The Jains and Buddhists questioned the existence of self, the reality of this world, and the need for rituals. Their story is well known, as is the response of the Vedic people to these challenges, and the reforms they evoked in rituals and theories via the Upanishads.

Here I shall discuss the Charvakas, whose response to the challenge posed by the shramana traditions was, in 20/20 hindsight, the closest to what modern philosophy has to say on the subject.

“The latest reconstruction of the text has it starting more or less as follows (1.1–8): Next then we will examine the nature of the reals.

Earth, fire, air and water are the reals.

Their combination is called the “body,” “senses,” and “objects.” Consciousness (caitanya) [is formed] out of these [elements].

As the power to intoxicate [is formed] out of fermenting ingredients. A human being (puruṣa) is a body qualified by consciousness. [Thinking is] from the body alone. Because of its presence when there is a body.

The world is varied due to variations in origin (janma ).

As the eye in the peacock’s tail.

(Adamson, Peter, Ganeri, Jonardon. Classical Indian Philosophy (A History of Philosophy) (p. 225). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition)

The Charvakas do not deny the fact that we are conscious, in fact self-conscious; and that each one of us has a self. Nor, unlike the Buddhists and Jains, do they deny the reality of a conscious self, as also of this world. Both are held to be real.

What they do say, like modern neuroscientists [theory of Emergentism] is that the conscious self arises out of your body naturally. Using a famous metaphor, Brihaspati explains consciousness arises out of the body, much like the spirits that arise out of a juice left to ferment. Consciousness inheres in the body and emerges from it under the right conditions. And when you die, it ends with you.

“Emergentism forges a middle path, holding that consciousness and other features of the mind are generated by the body, but are not mere impotent by-products, with all the real causation happening strictly at the physical level. Once they emerge, mental phenomena have their own explanatory force.”

A nice metaphor found in discussions of Cārvāka makes the point beautifully. A spark of flame is produced by rubbing two sticks together, and then the resulting fire can be a genuine cause of heat and burning, with the help of other materials. Analogously the body’s composition gives rise to such things as thoughts and desires, which can then cause further thoughts and desires.”

(Adamson, Peter,Ganeri, Jonardon. Classical Indian Philosophy (A History of Philosophy) (pp. 222-223). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition)

This was an idea brought to modern philosophy by Douglas Hofstadter in his classic book “Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid” in 1979 CE. But as we can see, Hofstadter struggled to find a metaphor to explain emergentism the way Brihaspati, the Charvaka Sage, did.

Like Stephen Hawking, this simple assertion by the Charvakas implies that all the rituals prescribed in the Vedas and Upanishads can’t deliver Moksha because your consciousness doesn’t survive death. That you achieve it by default is besides the point. Whatever things these rituals do, or don’t do, achieving liberation is not one of them.

The Charvakas are also realists. The world out there is not an illusion. It is real. We don’t know why it exists, or why we are here, to serve what purpose. But so long as we are here, let us live a good, orderly life, and keep looking for answers to questions we have regarding this world or ourselves.

Contrary to the general notion put out about Charvakas, they were neither hedonists nor epicureans. They were for a modest life of learning and contemplation. It is just that they didn’t believe in any of the elaborate theories of the world, or the Brahman, put out by priests, which could never be verified by any known means.

What could be a more sensible and practical attitude to life than the following quote manifests:

“Yet it [Charvaka philosophy] was still known in India in the sixteenth century, when it was explained to the great Mughal emperor Akbar that the Cārvākas “regard paradise as a state in which man lives as he chooses, free from the control of another, and hell the state in which he lives subject to another’s rule. … They admit only of such disciplines as tend to the promotion of external order, that is a knowledge of just administration and benevolent government.”

(Adamson, Peter, Ganeri, Jonardon. Classical Indian Philosophy (A History of Philosophy) (p. 215). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition)

The Charvaka epistemology basically accepts direct perception and inference as valid means of gaining knowledge. In that it is very much like the Samkhya School. Unlike the other six schools of Hindu philosophy, it rejects the authority of Vedas, and such testimony as cannot be directly verified.

“One of these commentators, named Purandara, is reported as saying that the Cārvākas “accept inference, although they object to anyone employing inference beyond the limits of perceptual experience.”

(Adamson, Peter, Ganeri, Jonardon. Classical Indian Philosophy (A History of Philosophy) (p. 218). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition)

The Samkhya school of Philosophy

It is not just the Charvakas who stand out among the Indian philosophical schools. Each has its brilliant and amazingly lucid moments.

Take Samkhya. It starts off with a theory of self, that comprises of two parts - the Purusha, which is pure consciousness and a mind that functions as its internal sense organ. The world is represented by Prakriti, the second part, which is inanimate, but capable of evolution because in Prakriti, the effect inheres in the cause. Like, say, curd inheres in milk, or wine inheres in a fruit juice.

As an example, think of simple atoms, that combine to form molecules, which in turn concatenate in chains to form proteins and so on.

Evolution in Prakriti is possible because at each stage, the whole produced is greater than the sum of the parts, and as such, capable of more and more diversity at every stage of evolution.

The two key ideas here - [a] that an unintelligent Prakriti or nature is capable of evolution without any intelligence [and therefore needs no creator] because of the fact that effect inheres in the cause; and [b] that the whole can be greater than sum of the parts; - is sheer genius. The earliest ideas of Samkhya date back to 600 BCE.

It explains evolution in a much more general form than Darwin’s theory. It is not complete though, and we shall see why Indian philosophy in general shies away from pursuing such ideas to their logical conclusion.

ATOM, SPACE, UNIVERSE & TIME

The Vaisheshika school was also founded around the beginning of the Common Era, and is well known for its contribution to metaphysics, among them the idea atoms or anu.

However, even more intriguing is the idea of Brahman as space, the foundational principle of the Universe.

The notion arose naturally from considering a couple walking down a path, with a man on the right, and a woman on his left. Years later, the sage, Kanada considers the same couple, but with a child in between them, and asks if the woman is still to the left of the man.

In trying to answer the question from first principles, Kanada makes a humongous leap of intuition. He considers the idea of a space, that pervades everywhere and in everything, [like the Brahman] and we may define the position of the man in relation to this space, independently of the relative position to woman or child. [Think of it as a cartesian coordinate system].

In much the same fashion, the position of the woman, and the child, can also be specified in relation to this space. Once we have the idea of space, we have a general way of determining what is to the left of the said man, or any man, or thing. Here we have the idea of Euclidean space, that eventually came to us with Newton some 1600 years later. But unlike Newton, our Kanada never quantified the idea, nor pursued it to its logical conclusion. He is content to have won his point with his rival.

While our sage was contemplating the idea of space as Brahman, he also has a fantastic intuition about time.

In general, Indian philosophy has no time for time, going so far as to dismiss the notion of time as something unreal, or a waste of time.

But this sage, moniker unknown to us, realizes that while we have to assign a different or unique space to each different person or thing, time is the same for all people or things.

Now, it need not be so. As modern physics would say, even time should be assigned uniquely. It is just that the speed of light is so swift, that time appears the same for all. Else it would be very much like space. Again, philosophy comes so close to intuiting reality, but then inexplicably shies away from pursuing the thought.

I have tried to illustrate my point with examples from Physics. But these by no means exhaust the sharp intuitions the sages offer.

PHILOSOPHY, GRAMMAR & LINGUISTICS

Bhartrhari, the grammarian, in his analysis of Panini’s grammar and Sanskrit’s linguistics, lands on the intuition that once you make “action” or the verb, the key to a sentence, you have already embedded into the sentence an agent, who must perform that action, and as also a purpose, for she performs the action. In short, there is no action in our language itself, that is without an agent and her purpose.

It is then no surprise that every analysis, in any of the philosophical schools, necessarily yields the idea of an ever-present self who thinks, dreams, feels, or does. The notion comes from grammar itself. Brahman then is in the language itself.

That intuition of an imbedded agent, with a purpose, in the language itself, is pure Chomsky. With one stroke, it debunks all of philosophy as nothing but a linguistic artifact, since every school of Indian philosophy was using Sanskrit, and panini’s grammar, at the beginning of the Common Era, having switched from Pali and Prakrit.

Then again, the theory of self in Samkhya is about as close you get to Rene Descartes “Cognito ergo sum” (I think, therefore I am) as you can imagine.

But the sages don’t say “I think, therefore I am.” Instead, like all loyal Vedic people, they say, “I think, therefore the Vedas must be true and I must be part of Brahman.”

Why do our schools of philosophy so blind themselves, despite their technical brilliance, and soaring leaps of intuition?

SANKARA, INDIA’S FIRST FUNDAMENTALIST

For this you have to understand Sankara and the chronology following his forceful intervention in the history of Indian philosophy.

All the six schools of Hindu philosophy, as also Buddhist and Jain traditions, are firmly grounded in their respective theistic texts.

Buddhism and Jainism arose to question the rituals in the Vedas, and are therefore rebel traditions. But they too acquired their own theism over time, and their philosophical schools too forgot all about enquiry into the truth for its own sake, and turned to full time offense against the Hindu philosophical schools, and to the defence of their own.

The Vedic schools, having been forced to give up most of the rituals in the Vedas because of overwhelming evidence against them, had to reinvent them through the Upanishads and Shastras, circa 800 to 600 BCE.

Their philosophical schools in the Common Era were fully committed to defence of the Vedas as the eternal truth or Sruti. The fact that the Vedas by then had been redefined as the original four texts plus the 60 odd Upanishads, was rarely brought out into the open. Just as now.

This confrontation between rival schools, and acute competition for state favours, meant that philosophy was a means of earning a livelihood, by proving your rival wrong, rather than an enquiry into the truth. The game was vicious. You not only had to prove you were right, but also show your rival was wrong.

Into this toxic mix descended Sankara, in the 8th Century CE, with his idea of Advaita Vedanta, for reviving and restoring Hinduism to its original pristine form, discarding the impurities that Samkhya or Vaisheshika had imported from rivals like Buddhism.

Sankara was India’s first fundamentalist, and his Advaita admits of only one thing - the reality of the Brahman - and nothing else.

An intellectual purge began.

Sankara smashed the Purusha-Mind and Prakriti dualism of the Samkhya as exegetically incorrect exposition of the Vedas. There was nothing real in the world except the Brahman. The rest was an illusion.

He likewise dismissed the metaphysics of the Vaisheshika school as nihilism because it had no use for the theism of the Vedas anchored in Brahman. Sankara instead held the that only Brahman was real, the world as we see it was a creation of our mind, an illusion, that we must set aside to discover the Brahman in us, whereupon, we are liberated. There no atoms, space or time.

Having shut up rival schools in Hindu thought, he went after the Buddhists, denouncing them for being foolish and mistaken because the Brahman was a reality they could not deny.

Which in a way is true because to achieve liberation, something in you must be liberated, but the Buddhists tied themselves into knots trying to explain what exactly was liberated upon achieving Moksha. Besides it was foolish to deny the reality of the world around you, that you could see, touch, and feel etc.

Sankara’s self-contradiction while attacking the Buddhists for denying the reality of the world, and his own attack on rival Hindu schools for holding the same world as real, didn’t go unnoticed.

He was severely criticized later on by his successors at the Vedanta School, like Bhaskara. But while he was alive, he held sway over all terrain, demolishing rival arguments with his towering intellect and compelling demagoguery.

The Hindu Schools could not really fight back Sankara because they were equally committed to upholding the authority of Vedas as Sankara’s Advaita Vedanta. Sankara was able to shut them up by his more competent exegesis of the Vedas.

It is noteworthy that Sankara came up with no new philosophy of his own. In fact, he even denounced empirical facts to be inferior evidence compared to exegetical fact. He was fully committed to the Vedas, and his exposition of the Bahaman in Advaita Vedanta was purely exegetical, based on the early Upanishads & Vedas.

Of the rival traditions, Buddhism and Jainism, both were heavily invested in the theory of karma, reincarnation and Moksha or liberation. Having denied the reality of the world, and conceded the need for liberation, they had no choice but to accept that there must be something in us that needs liberating. And this could well be the Brahman. The decline of Buddhism dates back to this Era, and follows the Conquest of Sind by the Arabs circa 712 CE.

So Sankara in the 8th century CE, practically single handedly, demolished what remained of Mahayana Buddhism, Jainism, as well as his Hindu rival schools of philosophy, to firmly establish the authority of the Vedas, and his school of philosophy, the Advaita Vedanta. Fundamentalism had triumphed.

That Indian Philosophy never recovered its old elan after Sankara, is part of our history. It took a while for tradition to pick itself up after Sankara; even after he had been denounced for his double standards.

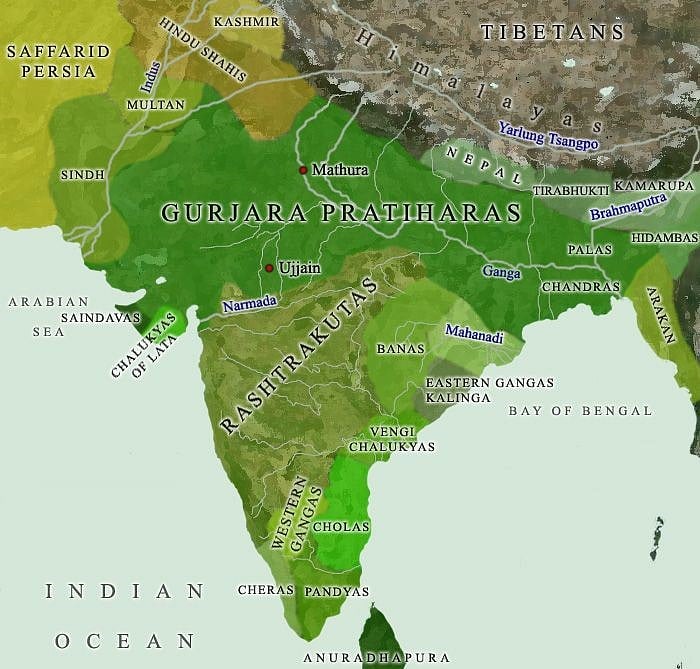

The post-Sankara period, especially after King Harsha [760 CE], is the really dark period of India history, spanning the late 8th to early 10th century of the Common Era.

It involved a long war of attrition for control of Kanauj, capital of the Middle Kingdom, between the Western Gurjaras and Pratiharas, on one hand, the Eastern Palas on the other, and both in turns, with the Rashtrakutas from the South. [See map.]

The three great powers left the land devastated by war and ripe for the taking by marauders from the North West, who came to loot, plunder, take slaves, starting with Muhammad of Ghazni in !001 CE. Ghazni raided the Indian plains 17 times. That should tell you something of the catastrophe that the Gurjaras-Pratiharas, the Palas, and the Rashtrakutas had wrought, by their fratricidal wars over 200 years.

It is noteworthy that none of the Indian schools of philosophy were able to stand up to the fiery demagoguery of Sankara’s exegetical extension of the Vedas because they had never done philosophy for an enquiry into truth for its own sake. Their philosophy has always been theistic, and within the framework of the theories of karma and reincarnation, never venturing to explore intellectual territory beyond the established paradigm.

The only ones to break free of the theistic texts, and pursue philosophy for its own sake, were the Charvakas, who earned the wrath and the enmity of all priests, and were stamped out at the earliest.

If their philosophy survives today, it is purely thanks to Jain syncretism, whose sages took pains to quote the Charvaka texts before refuting them. Else we would know nothing about them.

In our own tumultuous times, it might be worthwhile studying the phenomenon of Sankara of the 8th century, and his use of exegesis of the Vedas, to demolish practically all other traditions with the sheer force of his demagoguery.

The BJP/RSS are keen on establishing the Advaita Vedanta as more or less the only version of Hinduism there is. One cannot really predict where their idea of Indian philosophy and history will lead us to.

What they should note though is that you can’t have your cake and eat it too. So, if Advaita Vedanta stands, all else in Indian philosophy stands demolished. Like the Bhakts, you can’t take credit for the liberals’ liberalism, while denouncing them as Maculay-putras. Or like Modi, claim credit for Nehru’s liberal-secular credentials when abroad, and denounce him as a libtard at home, responsible for all our problems.

Coming back to the Modern day Charvaka, Stephen Hawking, and his theory of Big Bang, lets us see what he things about Cosmogony.

"The Euclidean space-time is a closed surface without end, like the surface of the Earth," he said. "One can regard imaginary and real time as beginning at the South Pole, which is a smooth point of space-time where the normal laws of physics hold. There is nothing south of the South Pole so there was nothing around before the Big Bang."

One of the key sutras in the Rig Veda says this world was born out of nothing. If any modern Charvaka is looking to a genuine exegetical origin for a new school of philosophy, rooted in the Rig Veda proper, she needn’t go far beyond Stephen Hawking, and this “Universe out of nothing” hypothesis, as the starting point of new Cosmogony.

The Charvaka spirit should never be allowed to perish. As Brihaspati would say, live your life in the present, and look out for answers to questions that interest you. That is the best life to live.

(The writer is an independent commentator. Views are personal)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 01 Oct 2021, 12:00 PM