The postman who always delivers

A day in the life of Renuka Prasad, a rural postal worker in Karnataka, who is not entitled to a pension and other benefits regular government employees enjoy

The windows of the local post office creak open, and the postman himself looks out through the window seeing us approach.

Renuka beckons us in with a smile into the post office, a single-room set up with a door leading to it from the foyer of the house. The smell of paper and ink greets us as we step into his small working space. He is stacking away what is the last post for the day. Smiling, he gestures for me to sit. “Come, come! Please make yourself comfortable.”

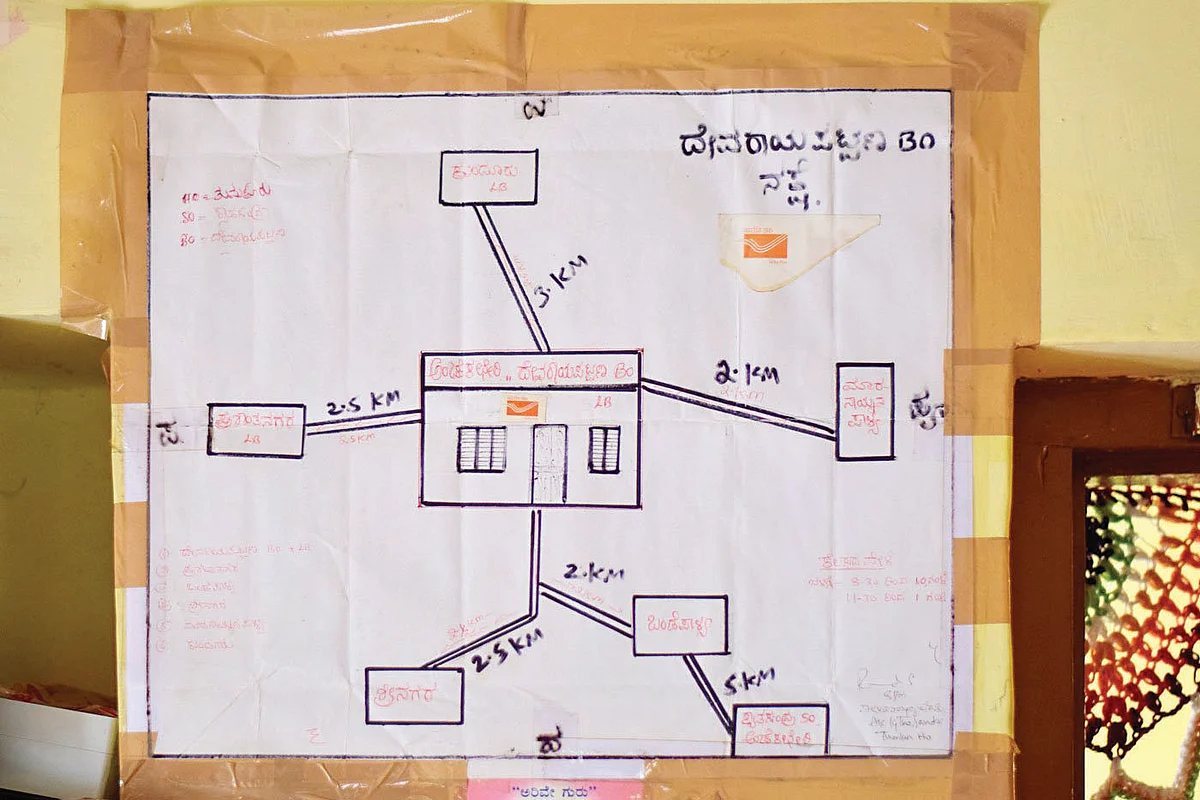

In contrast to the weather outside, the inside of the postman’s office and home is cool. The lone window is open to coax in the breeze. Multiple handmade posters, maps and lists hang on the whitewashed walls.

The small room is tidy and organised, as one would expect such an important place to be. A desk and some shelving area take up most of the room, but it doesn’t feel cramped.

Renukappa, 64, is a gramin dak sevak or rural postman in Devarayapatna town in Tumkur district. Six villages fall in his postal territory.

The official timings for this rural post office in Devarayapatna are 8.30 am to 1.00 pm, but Renuka Prasad, its only employee, often starts working at 7.00 am and continues until 5.00 in the evening. “Four-and-a-half hours is not enough to complete my work,” explains the postman.

The postman’s work starts with the postal bag of letters, magazines and documents that arrive in the morning from nearby Belagumba village in Tumkur taluk. He must first register all the mail after which he sets out to deliver them by around 2.00 pm every day.

The six villages he delivers to — Devarayapatna, Maranayakapalya, Prashantanagara, Kunduru, Bandepalya, Shreenagara — lie within a six-km radius. He lives with his wife Renukamba. His three grown-up daughters have moved out.

He shows us a small hand-drawn map hung above his desk with all the villages he needs to visit, how far they are, labelled with the four compass points in Kannada, and complete with a legend. The closest is Maranayakapalya, 2 km to the east. Prashantanagara is around 2.5 km to the west, Kunduru and Bandepalya 3 km to the north and south respectively, and Shreenagara 5 km away.

To traverse these long distances he has — like the stereotypical postman in stories — an ageing bicycle. Riding into each village on his bike and cheerfully greeting people who run to welcome him, Renukappa is the lone ranger out in the sun or pouring rain — the postman who always delivers.

“Renukappa, we have a puja at our house today. Do come!” a lady walking by in front of his house calls out to him. He beams at her and nods. Another passing villager waves to him and shouts a greeting. Renukappa smiles and waves in return. The warm relationship between the villagers and their postman is evident.

He covers 10 km on an average day, delivering the post. Before retiring for the day, he must note and account for everything he has delivered in a thick, worn-out notebook.

Renukappa says the development of online communication has led to a fall in the number of letters, “but magazines, bank documents etc. have doubled in the past few years, and so my work has only increased”.

Gramin dak sevaks like him are deemed ‘extra-departmental workers’ and hence not considered for emoluments, let alone a pension. They are involved in all functions, such as the sale of stamps and stationery, the transport and delivery of mail and any other postal duties.

Since they are not part of the regular civil service, they are not covered by Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules, 2021. Currently, the government has no proposal to grant any pensionary benefits to them, other than the Service Discharge Benefit Scheme, effective from April 2011.

After Renukappa retires, his monthly salary of Rs 20,000 will stop, and he will not receive a pension.

“Postmen like me have waited for so many years, hopeful that some change would happen. We waited for someone to acknowledge our hard work. Even if we receive just a small portion of what all those other pension recipients are given, say one or two thousand rupees, then that would be more than enough,” he says.

“I will have retired by the time this changes,” he adds wistfully.

His mood lifts when this reporter asks him about a poster with small cuttings, laminated and displayed on the wall. “That poster is a small joy for me. I call it the anchechiti poster,” he says. “This has become a hobby for me. A couple of years ago, the newspaper started releasing these stamps to honour famous poets, freedom fighters as well as other notable figures.”

So Renuka started collecting them as soon as they came out, cutting them out of the newspaper. “It felt nice to wait for the next one to come out.”

(Courtesy: People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines