Life in the caves of Nilambur

In the dense forests of Kerala’s Malappuram district, Asia’s last cave-dwelling tribe is fighting for survival. Yet their knowledge of local biodiversity may be critical to the Western Ghats

At dusk, a faint trail of smoke drifted from Kootanpara, a Cholanaikkan hamlet tucked deep inside the Karulai forests of Nilambur in North Kerala’s Malappuram district.

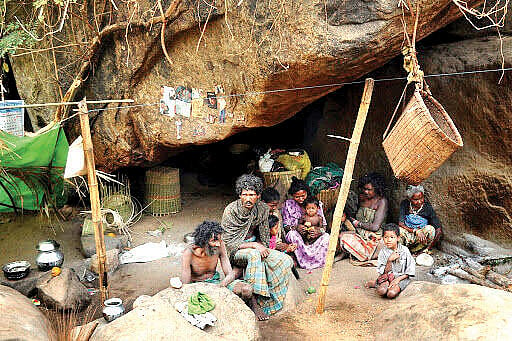

The scent of damp earth, fresh leaves and moss mingled in the air, blending with the faint smoke from cooking fires. Under a sky painted by the setting sun, tarpaulin sheets and shabby tents stretched across rock ledges, creating makeshift homes for families who once relied on sturdy caves.

The caves themselves, ancestral and once firm, are now caving in.

Rainwater leaks in, walls crumble and families huddle under fragile coverings, exposed to the cold, storms and the constant presence of wildlife.

This is the precarious world of the Cholanaikkans, Asia’s last cave dwellers, a community of just 249 individuals.

Their sustenance, once reliably gathered from the forest, is becoming scarcer. Wild animals, at a comfortable distance from habitation earlier, have become bolder. They invade settlements, overturn the balance of life, and have become a fearful presence in the daily life of this forest tribe.

Every day brings uncertainty, every night a quiet tension that never quite lifts.

There is only one slender lifeline connecting these hamlets to the outside world: the Manjeeri road, which stretches from the Nedumkayam check post of Nilambur forest division deep inside the forest. This narrow, treacherous path is the only route the Cholanaikkans take to access schools, medical care and rations.

Yet the road is fraught with danger, frequented by elephants, tigers and bears. At dusk, the forest closes in, and those who traverse it after dark are vulnerable in a world now almost not their own.

For generations, man–animal encounters were rare inside the biodiversity-rich Nilambur region, a crucial part of the Western Ghats that integrates the hills of Wayanad, Malappuram and Kozhikode in Kerala, with those of the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu. The Cholanaikkans’ rhythms and traditional knowledge kept them safe from wildlife ambushes.

But forest fragmentation, shifting wildlife corridors, the collapse of the forest food chain and increased human activity along this solitary path have escalated conflict. Animals, displaced or more desperate, now appear with alarming frequency.

The tribal community recounts multiple tragic encounters over the past 18 months. A woman returning from the distant ration depot recalls narrowly escaping an elephant charge: she had to abandon her basket of essentials as the animal passed through. A youth guiding children from a residential school had to leap into a ditch to avoid the sudden appearance of a tusker, the children screaming behind him. Tigers have been glimpsed prowling near the fringes of the hamlet. Bears have raided granaries, scattering the little food stock that families maintain.

These encounters are no longer isolated; they have become daily reminders of the precariousness of life in the forest for the last cave-dwelling community of Asia.

The tragic attack on Mani

The dangers of the Manjeeri road were made starkly clear on the evening of 5 January 2025.

Mani, a 37-year-old Cholanaikkan man, was returning home after dropping his daughter at a tribal hostel. In his arms, he carried his five-year-old son. Two young men, 18 and 19, accompanied him.

As shadows lengthened under the winter sun, a wild elephant emerged, catching the group unprepared.

In the chaos, Mani’s child fell to the ground, saved only by the quick-witted reflexes of those nearby. Mani himself was crushed beneath the charging elephant. He had to be carried more than a kilometre through difficult terrain to get to a vehicle that could rush him to Nilambur Taluk Hospital, but his injuries proved fatal.

The Kerala forest department announced compensation for the family, a gesture that hasn’t quite alleviated the pain that hangs like a shroud over the community.

The incident shattered the fragile sense of security the Cholanaikkans once held. Routine trips for school, rations or healthcare now carry the very real possibility of death.

Reflecting on the incident, Dr Vinod Mancheeri, the community’s first and only person with a doctoral degree, said, “Mani’s death is not an isolated tragedy. It is the result of years of neglect, a widening gap between the forest world and the promises of the [world] outside. Our people are not equipped to navigate the dangers that now surround them.”

A journey into the caves

On 17 September, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra became the first national political figure to enter these caves.

Nilambur forms part of her Lok Sabha constituency, Wayanad. No Kerala minister has ever before ventured into Kootanpara or any other nearby Cholanaikkan settlement, howerver —visiting a numerically insignificant community was not a political imperative.

But guided by Mancheeri, Gandhi Vadra walked the forest trail, through mud and rain and over rickety footbridges, to get to the settlement.

She sat among the villagers, the women and village elders, and took in their stories — of leaking shelters, ramshackle tents and caves that threaten to collapse. They spoke to her of nights filled with the rumbling of elephants, of children too scared to walk to school, and of clinics and medicines that remain out of reach.

In PGV, the villagers had an attentive listener, who left them with not just promises to take up their issues at the appropriate levels and to advocate for better physical infrastructure, but also to underline the need to accord dignity to a people whose existence is entwined with the forest itself.

In public remarks after her visit, she praised the Cholanaikkans’ resilience, their collective decision-making, and their profound understanding of the natural world. Their survival, she said, was inseparable from the preservation of forest ecosystems, water resources and the health of the Western Ghats.

The ARANYA project

The Kerala forest department, collaborating with Cochin College, Edakochi, and MES Mampad College, Nilambur, is now implementing the promising ARANYA (Animal Recognition and Alert Network for Yatra and Access) project.

This AI-driven early warning system is designed to alert Cholanaikkans to the presence of elephants, tigers and bears along the Manjeeri road.

Battery-powered wireless sensors, mounted at key points, will flash colour-coded signals — red for elephants, yellow for tigers, green for bears — alerting residents to danger. The goal is to provide early warnings, so that villagers can retreat to safety, avoiding deadly encounters.

K.S. Anoop Das, head of conservation ecology at MES Mampad, cautions against complacency, however: “Technology can save lives, but it must be paired with justice — reliable roads, health access, housing and acknowledgment of forest traditions.”

The story of Dr Vinod Mancheeri

Dr Vinod Mancheeri, born in the Cholanaikkan hamlet of Mancheeri, is a rare specimen, a bridge between the forest and the wider world.

His parents, forest-dependent and barely literate, raised him immersed in the rhythms and knowledge of the woods. Early schooling drew him out with small incentives — like fruits and new clothes — leading him to residential tribal schools, and eventually to higher education in town. He earned a PhD in applied economics, becoming the first person from his tribe to hold a doctoral degree.

Vinod’s work is a vital chronicle of the Cholanaikkans’ hardships, documenting how isolation, cultural alienation and lack of infrastructure imperil survival. He has been instrumental in focusing attention on the community’s plight and was responsible for drawing PGV’s attention too.

“Our people have always lived in harmony with the forest,” Vinod says. “But harmony requires safety, recognition and support.” Without these, he says, life is reduced to a battle for survival.

A history of silence and resilience

From the 1960s onward, when forest officials first formally recorded the Cholanaikkans, their story has been largely untold.

Census records miscounted them; their language and customs were often misunderstood or exoticised.

Schools were distant, roads barely navigable, healthcare facilities sparse. Promises of housing, welfare and better connectivity were routinely deferred or diluted into photo-ops and announcements.

Yet, the Cholanaikkans persisted.

They survived on tubers, honey, small game and fish. They rejected resettlement schemes that aimed to relocate them from their ancestral caves. Even as wildlife pressures, climate change and the threat of erosion of natural resources increased, they preserved what they could — local knowledge, language and an identity rooted in the forest.

Today, their caves leak. Tarpaulin roofs flail in high winds. The forest, once a safe cradle, has become a corridor of risk. Children fear not just legendary monsters but also elephants that brush against their fragile shelters, whose charges can be fatal and whose rumbles can wake the terrified.

Though they are forest dwellers, the Cholanaikkans are ill-equipped to contend with threats from the wildlife that surrounds them.

Yet the Cholanaikkans’ knowledge is irreplaceable. Their vocabulary is arcane but their understanding of the local flora, fauna, medicinal plants and seasonal cycles is vital, offering crucial insights into the biodiversity of the Western Ghats.

Their social structures, winter shelters and animal-tracking mechanisms inform conservation efforts and cultural heritage studies.

Losing them would erase a living archive of human ingenuity and adaptation.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines