Mrinal Sen’s Chinu: The absent protagonist

In his iconic film ‘Ek Din Pratidin’, Sen reveals through Chinu, a working girl, the insecurity of middle class life and the claustrophobia of middle-class morality

The “absent” protagonist in a film can be a very important character. She/he might remain almost entirely absent from screen yet makes her/his presence felt in different ways while keeping the suspense alive.

There are several memorable Indian films that come to mind. Shaji Karun’s Piravi defines a father’s journey to find his missing son who, in fact, has been killed and his body is never found. But the father does not know this and is confident that if searched properly, the boy would be found. We never see the son throughout the film.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Mathilukal, an autobiographical account of Vaikom Muhammad Bashir, a well-known writer in Malayalam, recreates his experience of being in prison where he fell in love with a woman prisoner, who he never saw as she was always on the other side of the huge prison wall. The day they planned to meet, India was declared independent and Vaikom was set free.

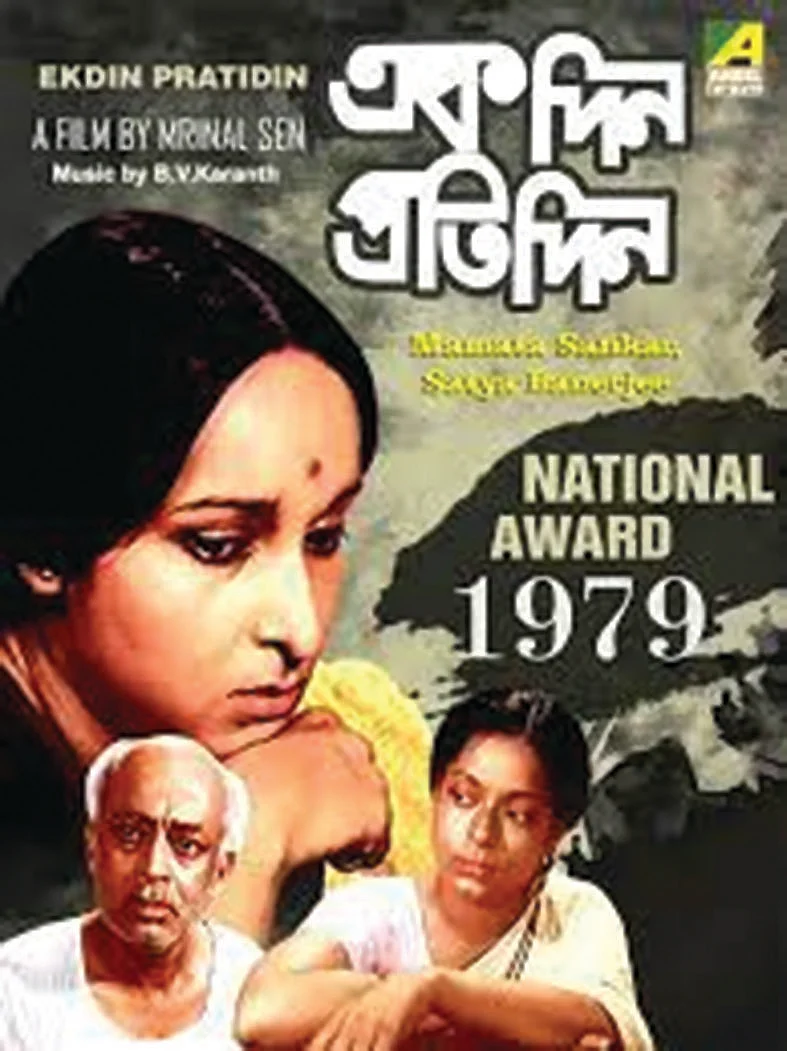

Mrinal Sen’s Ek Din Pratidin (1979) is another iconic film with the protagonist missing. The film reflects the filmmaker’s concern and anguish for the middle class, bound by narrow conventions and false moral values.

Ek Din Pratidin, based on Amalendu Chakravarty’s Abirata Chenamukh (Known faces, endlessly) describes the happenings of a day and night in a lower middle class complex of flats where everyone knows everyone else and there is little privacy. In one of these flats, Chinu, the elder of two daughters and the sole earning member in the family of six, fails to return home one evening.

As the family waits anxiously for Chinu’s return, the anxiety of her physical safety becomes secondary to the anxiety of what neighbours might say, think or do. Sen reveals the insecurity of middle class life and the claustrophobia of middle-class morality.

Underneath the actual events lie the unresolved attitude towards a working daughter who cannot be treated in the same manner as a working son. When she returns at dawn, the relief is so great that no questions are asked. But in that long night, values and shifting perspectives are examined and lay bare the anxiety for the future and possibility of survival.

Sen had told this writer about how Satyajit Ray asked him about where Chinu could have been that night. Sen had laughed and said, “I do not know myself where she had been. My concern is about the impact of her remaining away the whole night on her immediate family, on the landlord of the flat they live in and on their neighbours.”

Mrinal Sen’s 99th birth anniversary was on May 14 this year.

In Ek Din Pratidin, Sen sought to make the point that not all working women are economically independent. Chinu’s 'independence' is compromised by her responsibility towards each member of the family. Whether such responsibility is acquired, circumstantial or coerced become irrelevant.

Whether she wants to take the responsibility is questioned. For women like Chinu, the responsibility is thrust on them, whether they like it or not. Once she accepts the burden, she finds there is no escape or exit. Chinu’s status as a working woman does not give her freedom. Instead, it traps her. Her earnings are usurped to fulfil the needs of the family, for the good-for-nothing older brother's pocket money and for the younger sister's education.

The film ends with Chinu's mother emerging to light the earthen stove as she does every morning. She is distracted for a moment by an aeroplane flying above. The plane flying away is symbolic of modernity and freedom eluding the likes of Chinu and her mother.

Nothing has changed in their lives. The world may be speeding ahead but that does not affect these women in the least. The camera comes down to focus on Chinu's mother, trapped behind the bars on the window, beginning the drudgery of one more day.

Chinu’s absence is both metaphorical and real and when she returns, she understands her position in the family but she cannot opt out of it. Does she really even want to?

(Shoma Chatterji lives in Kolkata and writes on the arts)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines