Reel Life: The game of light and shadow

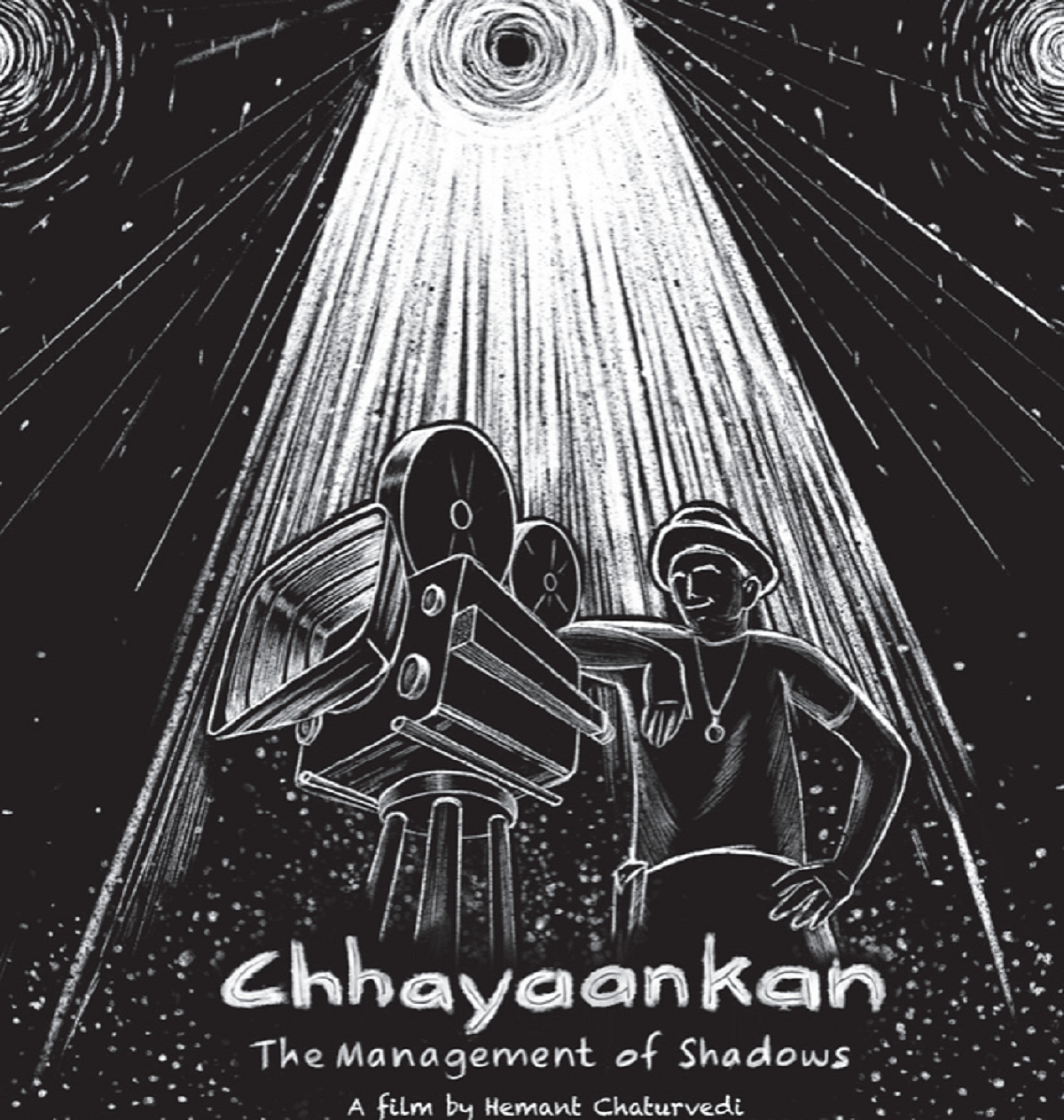

‘Chhayaankan’ explores how artistes challenged technology in the 20th century while now it’s technology challenging the artiste, and how the mind, philosophy of a cinematographer reflects in his work

There’s a scene in cinematographer Hemant Chaturvedi’s new documentary, Chhayaankan: The Management of Shadows, where cinematographer-filmmaker Govind Nihalani remembers talking to iconic lensman V.K. Murthy about legendary Guru Dutt’s death. “I cried more for myself than him,” Murthy told him. An expression of loss, not just of an individual, a friendship but, most so, of an extraordinary creative collaboration. A moment later actor Waheeda Rehman recollects the amount of time Dutt gave Murthy to perfect the light and shade effect in Kaagaz Ke Phool. It was all about striking a perfect rapport.

A kind of rare teamwork, based on trust, that cinematographer Nadeem Khan sensed with David Lean and Freddie Young and Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski. A kind of trust cinematographer Baba Azmi acknowledges having got from Rahul Rawail while shooting Arjun.

Nihalani has the last word in this segment of the film when he underscores that creativity in cinema is about the vision of the director, finding crystallization through the eye view of the cameraperson.

The cinematographer-director relationship is one of the many issues that Chaturvedi (Company, Maqbool, Makdee) touches upon in his sprawling film, which covers every possible aspect to do with cinematography— the practitioners and their life story, their body of work, the equipment, the Mitchells and Arriflexes, the art and craft and the mileposts in the evolution. It is a homage, a slice of nostalgia but more than anything else a piece of significant research, a vital record of history and an audiovisual archive of sorts of the people and the times.

He puts almost every colleague and member of the fraternity—14 veterans—in the spotlight. Besides Nihalani, Khan and Azmi, there are Peter Pereira, Jehangir Chaudhury, Pravin Bhatt, AK Bir, Barun Mukherjee, late Ishwar Bidri, Dilip Dutta, Kamlakar Rao, Sunil Sharma and RM Rao.

What is lacking is the voice of women cinematographers, perhaps because there were barely any in the Hindi film industry in the period that Chaturvedi zooms in on. B R Vijayalakshmi is regarded the first Indian woman cinematographer who worked in Tamil films of the 80s and the 90s. Fowzia Fathima, Savita Singh, Anjali Shukla, Deepti Gupta, Priya Seth, Archana Borhade have gained ground in filmdom more recently. It’s for actor Waheeda Rehman then, with a great deal of interest in photography herself, to provide a unique perspective from the front of the camera.

The 40 odd hours of footage has been structured in the film as a long, free flowing, stream of consciousness conversation with Chaturvedi moving back and forth with each of his dramatis personae. However, each of these discussions will be edited and uploaded as standalone interviews on YouTube.

There are interesting tales and delightful anecdotes about how cinematography came to some of them fortuitously. Khan, for instance, was studying nuclear physics when he moved on to his true vocation. He recalls how Muzaffar Ali’s Gaman came his way. He was supposed to assist Jacques Renoir but took charge independently when Renoir couldn’t commit to the venture.

SM Anwar used to clean sockets and cables for a company in Pune till he caught the eye of cinematographer Dwarak Divecha, who got him on board as the camera operator on Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay. Anwar went on to work as the cinematographer in Sippy’s Shaan, Shakti and Saagar.

Pereira worked for Homi Wadia in the late 50s and 60s for a royal salary of Rs 50, commuting all the way from Vasai to the studios. Rao marched on and took huge strides on the reputation that any girl he clicked would get married quickly. For Chaudhury it was a serendipitous coming together of his interests in meteorology, chemistry and architecture and interior design, besides the fact his family already had members in the film industry (cameramen Jal and Fali Mistry and actor Shyama) and his father ran a theatre in Indore.

There are conversations on the role of the cinematographer and his presence on the sets—commanding, dominating, controlling, most so about getting things organised and done, quietly and calmly.

Nihalani and Bir talk about how image was deployed to create an emotional response and dramatic realism, how it was all about creating illusion of reality and how significant changes were brought into cinematography by the parallel cinema movement. The insistence on naturalism had a major role to play, states Nihalani, as did the new crop of trained actors who wanted to create characters on camera than just look good. “It brought a different energy in to the image,” he says.

Nihalani also talks about how artistes challenged technology in the 20th century while now its technology challenging the artiste. Chaudhury dwells on it further—how the mind and philosophy of the cinematographer reflects in his work.

Then there are sweet sidelights. Pereira’s affection for Meena Kumari and how she used to drop him at Dadar station to have him catch the last train to Vasai. Simultaneously there is also the questioning of star system and how its misuse adversely affected the craft.

Interestingly, a graduate of the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia, Chaturvedi, decided to move on from a very successful career in the film industry and gave up on cinematography in 2015, and has since then focused on the documentary and still photography work. Texting from Madikeri in Coorg, he tells us about another passion project he is now on—profiling the single screen theatres across India. “In 2019/2020 and now again in 2022, I’ve driven over 30000 kilometres in my jeep and photodocumented almost 800 old single screen cinemas across 12 states. From Srinagar to Madikeri,” he writes.

If the two photos of theatres he shared with us—Rama Kanthi, Mangaluru, 1946 and Shakti, Bagalkote, 1948—are anything to go by, there are some beauties in his work ahead to feast our eyes on. But as he describes them to us, on a more sobering, severe and urgent note: “Such extraordinary spaces, and such a shaky future!” Turned worse by the onslaught of Covid-19. If only they could be conserved and restored for the ages, just as Chaturvedi has captured the cinematographers on camera for posterity.

(This was first published in National Herald on Sunday)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines