Vishal Bhardwaj's films: Pygmies in and out of power

Vishal Bhardwaj’s films explored various aspects of ‘power’and seem even more relevant at a time when the State is exercising absolute power

Some filmmakers create cinema that changes the way we see the world around us and its politics.

Some of Vishal Bharadwaj’s cinematic takes were inspired by some of the greatest stories ever told (The Shakespeare Trilogy: Macbeth, Othello and Hamlet; Ruskin Bond’s Susanna’s seven husbands; Charan Singh Pathik’s Do Behnein), are contextualised in varied kinds of politics in India. Going beyond the arc of politics of power from the original texts, setting them in seats of political conflict specific to India, threw the realities of the times we live in in sharp focus.

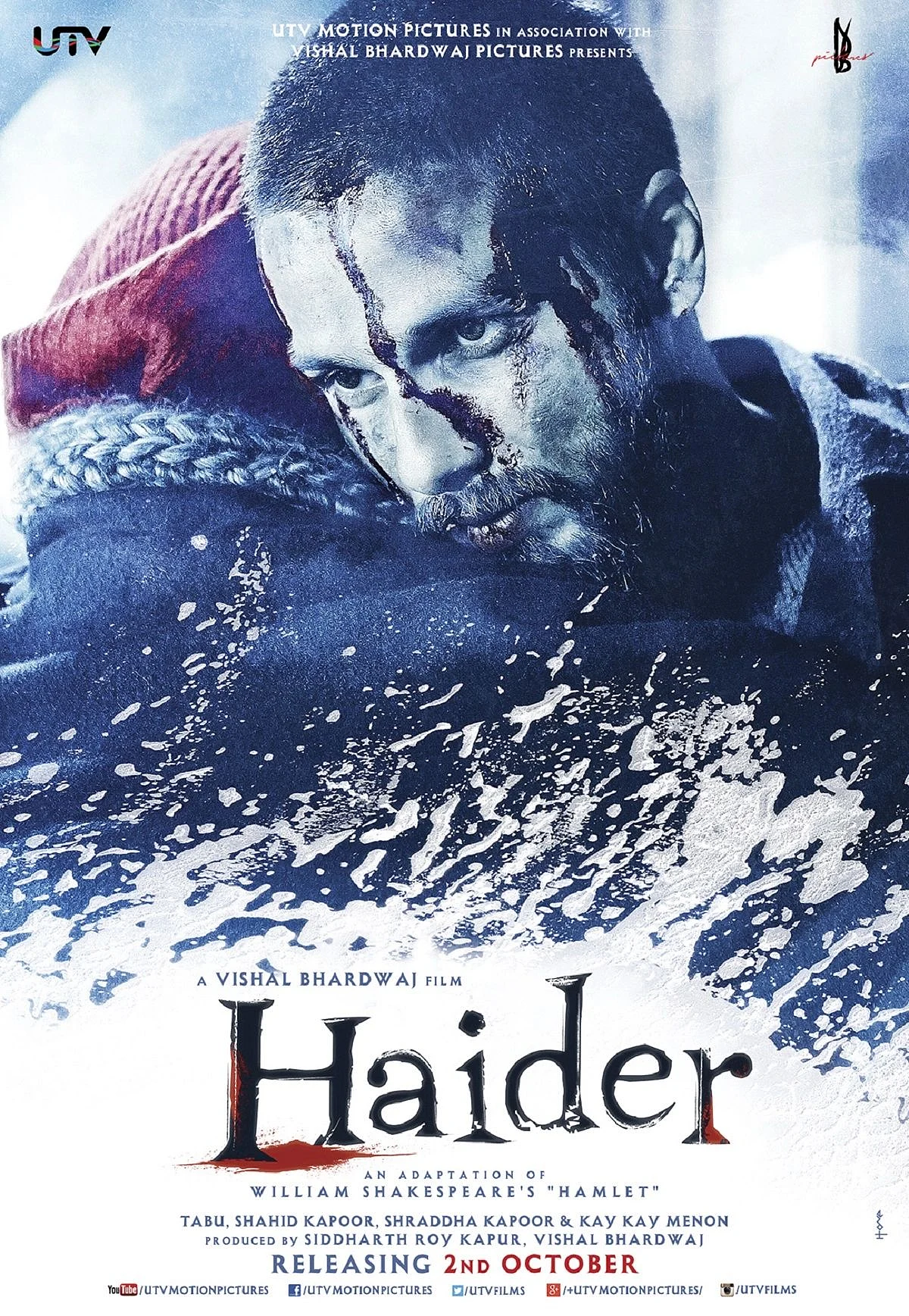

They reflect on politics of oppression, the need to resist, and the very human impact oppression has on the lives of citizens. His directorial ventures from the very beginningMakdee (2002), Maqbool (2003), Omkara (2006), Kaminey (2009), Saat Khoon Maaf (2011), Matru ki Bijlee ka Mandola (2013), Haider (2014), Pataakha (2018) -- all view politics and oppression through different lenses.

It has often been lamented by lovers of cinema that it would not be possible for a filmmaker to make and release Haider in today’s age of intolerance and censorship. Setting Hamlet within Kashmir, Basharat Peer and Vishal Bharadwaj’s sensitivity, deep understanding of politics and the conflict of Kashmir and their singular focus on showcasing the impact of oppression on human lives and minds, is unrelenting in its gaze.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) that gives sweeping power to the army for arresting those they suspect, sentencing families to nothing but an endless wait, inhuman torture, political nexus and little or no space for kindness beyond binaries-- asks questions in each frame and dialogue. Shahid Kapoor’s turn as Haider, his scene on what AFSPA means to the people of Kashmir, is testimony to trauma and fear that people of the state have lived in for decades.

There are two scenes in Haider, that stay with one long after the film is over. Haider going through the bodies of the dead to find his father and hoping he doesn’t, as one still alive escapes the mound of corpses, and the other when a civilian is afraid to enter his own home till he has been adequately frisked.

‘Inteqam se sirf inteqam paida hota hai, aur jab tak hum apne inteqam se azaad nahin honge, koi azaadi humein azaad nahin kar sakti’ in Tabu’s (career best as Gertrude or Ghazala) trembling voice reminds us of the power of individual kindness. And yet, with such consistent infliction of violence and trauma, how do we still find kindness within our own selves? Haider asks these pertinent questions.

Cinematically, the film is cast to perfection, with the characters living and breathing their own, going beyond the tale by the bard. Roohdar as the ghost of Hamlet’s father, with the inimitable Irrfan’s haunting voice reciting ‘Shia bhi mai, sunni bhi mai, mai hoon pandit…’ is a scene to be revered for all time-- both for its writing and its performance. That breaks down identities and unites them in oppression.

Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola looks at the oppression of farmers, and the nexus between industrialists and politicians that bleeds them dry. The politics of land, who toils versus who owns, whose profits versus whose survival, are the key and critical themes in the film.

The need for an educated person, who doesn’t appropriate the struggles of the farmers, but sees himself as one of them, gains the trust and finds economic solutions to liberate the farmers from oppression, indicates potential solutions to what seems like a systemic cycle too tight to break. The film does not shy away from looking at class struggles, what poverty induces, and the politics of the powerful ensuring the powerless remain powerless. With that, demonstrating what it can mean for the oppressed to recognize their own power and decide to fight. Shakespeare is visible again as protagonists read Macbeth.

The satire in the film is unmistakable, with artists of a different land being ‘bought’ without them even knowing it. Matru’s references to the bourgeoise sense of capitalism, the awareness of its own politics of the oppressed, the constant attempts to fight through ‘Mao’ and the desperate need to break the systemic cycle are important reflections for those benefiting by the systems and yet comfortably distant from them- - essentially the upper middle class of India that stays comfortably aloof, as long as food continues to reach their tables.

Gender based oppression also finds space, with a woman educated but still merely a means to a larger goal, of consolidation of power between the industrialists and politicianswhere her desires and dreams are to take a backseat in the larger scheme of things. Where the film falters though, is in its eclipsing of caste, and the agency of the woman still being robbed, as decisions are taken for her than with her.

Makdee and Pataakha (almost bookends to his filmography until now) are both set in villages. And while the politics is not overt, it is easily recognizable. In both, it is the women who are at the centre. One who fuels her image as the witch as she orchestrates a myth and in tandem with police officers (again collaboration with establishment), continues her plan as a con-woman.

And the latter two in Pataakha, who are driven by their need for liberation, the ability to see dreams and fight for them to be realised. And which each of these, the ability to fight for their love and companionship. Pataakha delves into how different the ambitions are for both protagonists, joined by the thread of going beyond being someone’s partners.

Satirical and outrageous, it is the negotiations that both women make to fulfil their dreams, that throw into relief, what fighting for their own dreams actually means. Their partners, and their father, are allies in the journey of these dreams finding fruition.

7 KhoonMaaf, possibly Bharadwaj’s most moody outing, looks at what desire can do. The film tethers itself on the refusal of oppression whether emotional or physical- with a woman at the centre, unapologetic about going through partners at her will, deciding their fate based on their behaviour towards her.

While Haider’s politics emerges from the setting of the story itself, Omkara comes alive in its context. The elections of Uttar Pradesh, the need for power, and deceit that follows is palpable in the narrative, both in Othello and in its adaptation. The orchestration of incidents as Langda Tyaagi (Saif Ali Khan in his career best as Iago) feels cheated of the power he felt he deserved, looks at oppression of a different kind. Of what universal power can do, not intercept personal ambition.

Caste finds a mention as Dolly (Kareena Kapoor as Desdemona), is denounced by her father for choosing to be with Omkara who is of a lower caste and a political goon. All three women protagonists are oppressed by their male partners. While only one fights back violently, the unforgettable Indu (Konkana Sen as Emilia).

Maqbool too looks at oppression. Set in the underworld of Bombay, there are many layers one witnesses in the Vishal Bharadwaj masterpiece, with distinct similarities with Omkara. Abbas Tyrewala’s script showcases the constant fight for power between the State, the underworld, the distinct nexuses each of these ensue to have one man stay in power, despite rivalry within the underworld-- replete with violence and gore. And the hegemony of a single source of power, and everything else it obliterates. The oppression here comes straight from power -- power of money, control and the need to oppress. Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah as the police officers and the witches of Macbeth show this turn of oppression as their loyalties, despite personal threat, stay with those they believe can protect them.

(This was first published in National Herald on Sunday)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines