Char Dham/Uttarakhand: High on Hindutva

Reckless ‘development’ work in the Char Dham pilgrimage circuit is threatening not just the fragile ecology of the region but entire villages and towns—and human lives. But is anyone listening?

Devout Hindus like to refer to Uttarakhand as Devbhoomi (land of the gods). The Char Dham (literally: four abodes) Yatra—of the shrines in Yamunotri, Gangotri, Badrinath and Kedarnath, in the upper reaches of the Himalayas—is tied up in their imagination with ideas of moksha (salvation) and spiritual bliss. For that very reason, the Char Dham destinations are also a crucible of the Hindutva dream, and the reason for the Modi government’s blinkered focus on developing it as tourist circuit.

Thousands of crores have been spent on constructing four-lane roads in the region, besides train and air connectivity, to facilitate the movement of millions of pilgrims to these hotspots every year. Sadly, though, all this money will likely go down the river because the grandiose Kedarnath and Badrinath Master Plans are being executed on moraines (unstable paraglacial sediment) in areas prone to natural disasters including landslides, flash floods and avalanches.

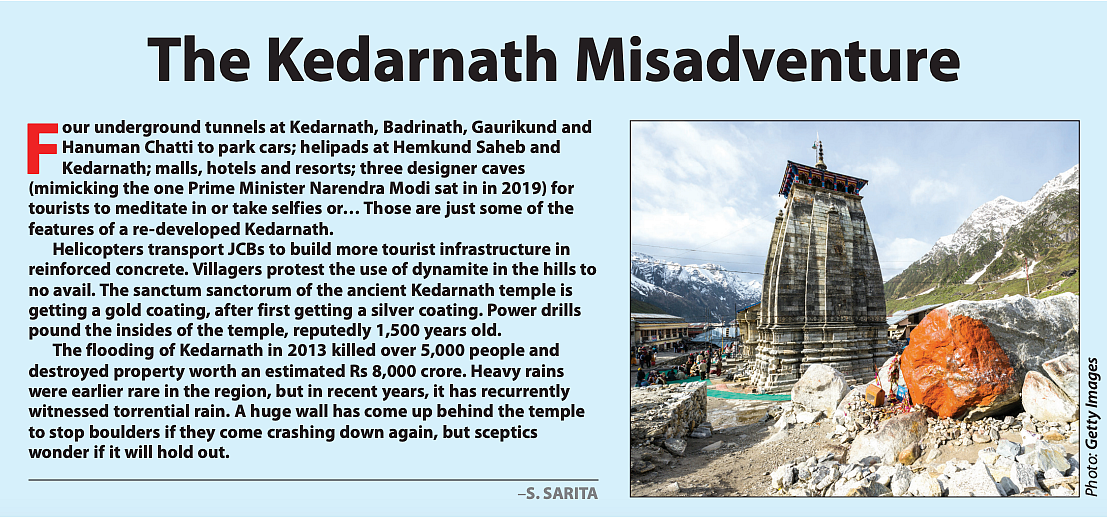

Kedarnath, a particular favourite of Prime Minister Narendra Modi (recall the cave shrine photo-op?), is witnessing a proliferation of fancy resorts and hotels, which can all be swept away in a matter of minutes—as happened in June 2013, when calamity struck this temple town in the form of an avalanche and the overflowing waters of the Chorabari Lake.

Three avalanches have already hit Kedarnath in a span of 10 days between end-September and the first week of October. These fell 3-4 km short of the famed Kedarnath temple, but the devastating avalanche that hit the higher reaches of the Uttarakashi hills on 1 October killed 27 mountaineers with some still missing.

The Himalayas are a young mountain chain, made mainly of shale, which is a weak sedimentary rock. Scientists have warned repeatedly against over-construction and the mindless commissioning of hydro projects (over 500 of them) in an eco-sensitive area, given also that global warming is causing erratic and heavy precipitation, resulting in more avalanches. Their warnings have fallen on deaf ears.

All these projects are being executed under PM Modi’s direct supervision and he remains impervious to the consequences; in the past four months, both Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh have witnessed an unprecedented number of landslides. According to NGOs active in these areas, the Garhwal hills are witnessing three landslides a day. Himachal reported at least 246 deaths in 2021 due to natural disasters.

In Himachal, 19,000 villages have been declared to be at risk from landslides. Uttarakhand has a higher number of unstable zones—the Bhagirathi Valley alone has 235 landslide zones, as per a Department of Science and Technology report submitted in Parliament. Sushila Bhandari, an environmental activist who was jailed for 54 days during the Tehri dam agitation, along with several women who live in villages around Kedarnath, complains about the frequent use of dynamite to build tunnels and widen roads.

Bhandari said in a phone conversation: “For the past three years, it has been scary to step out of my house because dynamite blasts have increased the frequency of landslides; we worry all the time.”

She even called on Union home minister Amit Shah when he visited Kedarnath, along with a group of activists, to draw his attention to the risks. Shah apparently assured the delegation that no dynamite would be used in these mountains but, of course, only to fob them off—there is no sign it will stop any time soon.

The 125 km Rishikesh-Karnaprayag railway line, being built at a cost of Rs 20,000 crore, to take pilgrims up to Badrinath and Kedarnath will have 35 bridges and 17 tunnels. The Devprayag-Lachmoli 15 km tunnel is claimed to be the longest in the country. The blasting that is going on in these stretches means more landslides. Cracks have developed in over 220 homes in Sweeth, Dhamak Nakrota and Dobripanth villages, and irate villagers have stepped out for protests; earlier this year, villagers blocked traffic on the Rishikesh-Srinagar road for five days. They complained to the Srinagar sub-divisional magistrate Ajay Veer Singh, who recommended the Railways compensate these villagers. But the Railways brushed aside even the paltry Rs 1.54 crore he’d recommended, insisting they had adhered to scientific norms of construction.

Dr Vikram Gupta, a scientist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, says scientific advice simply goes unheeded. First, roads in these areas cannot be that wide— scientists have repeatedly warned against building roads that are 10-plus metres. Hemant Dhyani, an activist with the NGO Ganga Avahan explains that the Himalayan terrain can support roads upto 5.5 metres wide—this was also the norm till 2018.

He says the government decided to widen the Char Dham roads to 10-plus metres to justify hefty tolls; this is being done in Himachal as well. The ministry of road transport and highways is spending Rs 12,000 crore to widen the 900 km Char Dham stretch, “which works out to more than Rs 8-10 crore per kilometre, whereas the typical budget for hill roads is around Rs 80 lakh per kilometre,” says Dhyani.

That apart, contractors engaged for these road construction projects in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh are not following standard operating procedures for cutting/ protecting mountain slopes, Gupta says. He and a group of scientists had identified 44 landslide-prone zones in Himachal, of which five were marked as extremely unstable, needing immediate attention.

Dr Ravi Chopra, a leading environmental scientist and founder of the People’s Science Institute, headed a high-powered committee constituted by the Supreme Court of India. The committee recommended an intermediate road size for the Char Dham project, but this was overruled by the roads and highways minister on grounds that the armed forces needed wider roads. Chopra resigned from the committee in disgust, after issuing a brief statement that his hope that the committee could protect the fragile ecology of the Himalayas had been “shattered”. ‘We are allowing our bureaucrats and engineers to get away with an increasing number of environmental disasters,’ Chopra said.

It is not even only the upper reaches of the Himalayas that are being affected by largescale deforestation, indiscriminate mining and mindless urbanisation. A 2011 IIT Roorkee study revealed that landslide-prone areas in the Doon valley had increased from 20 to 100 in the past decade.

The landslide inventory map of 2021 shows over 100 landslide zones in the Doon valley with two serious repercussions. Being an earthquake-prone zone, this could result in a shifting of the tectonic plates. Another even more serious problem is that such unprecedented construction is destroying the natural springs and aquifers around the capital city.

Both the Shivalik range and the Himalayas are key watershed areas, but the land mafia has been given a free hand to encroach on all crucial river-catchment zones. Sand mining is rampant, and Uttarakhand has lost as many as 38 bridges to unprecedented sand mining.

The latest perfidy is the construction of a 210 km access-controlled Delhi-Dehradun highway, connecting the Akshardham temple to Dehradun, at an estimated cost of Rs 8,300 crore. This is being built ostensibly to reduce travel time from Delhi to Dehradun “from six hours to around 2.5 hours”—as per government’s claim—when there is already a newly constructed four-lane road connecting the two cities! This new road alignment will cut down Dehradun’s legendary sal forest, which Dr Ravi Chopra describes as “the soul of the state”. It will also cut through the Rajaji Tiger Sanctuary and the Shivalik Elephant Corridor. Dehradun-based environmental activist Reena Paul, who has filed a PIL in the Nainital High Court against this new road, warns that a 12 km stretch of this road is being constructed as an overbridge on the riverbed.

“Several big and small rivers including Mohand Rao, Sukh Rao, Solani, Chillawal, Chika Rao and Bindal Rao emanate from here, and this construction will affect the entire water security of western Uttar Pradesh. The Asharodi ridge, on which this expressway is being built, is the source of 20 rivers, including the Hindon and the Solani,” says Paul.

Disposal of muck is another big problem. In June 2021, a former Uttarakhand minister Dinesh Dhani held a day-long dharna in Tehri district protesting the indiscriminate dumping of debris into rivers and valleys. “[This] muck is now flowing into our homes and farmland, destroying our crops,” Dhani says. Several towns and villages are affected by this construction onslaught. The village of Raini, home to the Chipko movement, has been declared dangerous and its residents are being evacuated to a safer place. Floods overwhelmed the village when an avalanche destroyed NTPC’s 520 MW Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower project in February 2021.

Raini’s pradhan Bhawan Rana laments: “A village that gave the hills a fighter like Gauri Devi in 1973, who led the Chipko movement, has now become a victim of the government’s policies, and we are all being forced to move out of our ancestral homes.” It’s not even just the villages that are sinking. S.P. Sati, leading geologist and head of department of Basic and Social Sciences, Garhwal University, describes how city after city in these fragile mountains is sinking. “Joshimath, the gateway to the Badrinath temple and to Hemkund Saheb, and several other cities are sinking as they have been built on a thick cover of landslide material, which is inherently unstable,” Sati points out; Gangotri, Uttarkashi and Gopeshwar are some other towns that are sinking, Sati warns.

Meteorologist Mahesh Palawat of Skymet warns that increasing extreme weather events will see a sharp rise in heavy rainfall, cloud bursts, landslides, mud slides and flooding.

Before the elections in 2019, Modi swaddled himself in an orange shawl and sat outside a cave in Kedarnath; that master of theatrics was trying to impress upon his gullible audience that he was all ready to take sanyas if they didn’t vote him in again. But villagers ask how a sanyasi could green signal the gold plating of the walls of the holy Kedarnath, a shrine to an ascetic god. Hinduism’s holiest cities might just go under because of the monumental follies of this ardent bhakt.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 15 Oct 2022, 9:00 AM