Electoral bonds: How India's super rich are slyly buying their way to power

Behind a veil of secrecy, electoral bonds seem to have ushered in a second ‘Company Raj’

Why do you want to keep the identity (of the purchaser of electoral bonds) a secret?” a Supreme Court bench headed by the then CJI Ranjan Gogoi asked Attorney General K.K. Venugopal in April 2019.

“All industrialists have to knock on the doors of the government from time to time for licences, exemptions etc. If it is known that they gave 50 crores or 100 crores to one party, they would be targeted by the rival parties,” replied the Attorney General.

Justice Deepak Gupta, who was also on the bench, exclaimed, “You are talking of the right of the donor to secrecy. But the right of the voter to have transparency is an important part of democracy!”

“The voter has the right to know what? They already know every single aspect about the candidate. Why are they concerned about the source of money of the political party…” an agitated AG shot back.

The desperation of the government was evident. The general election was round the corner and it could not possibly afford a court stay on the controversial electoral bond scheme or an order freezing the special accounts which held the proceeds of the bonds. With the Lok Sabha polls only 15 months away, the apex court is once again scheduled to hold a hearing on petitions challenging the electoral bonds (EBs).

After having refused to stay it for the past five years or pass final orders, not many observers are hopeful of the court striking it down. The Justices have spoken in its favour, observing that the scheme has sufficient checks and balances. Ranjan Gogoi, who is now a Rajya Sabha member, does not mention the case in his autobiography, Justice for the Judge. When quizzed by a TV interviewer during his book promotion, Gogoi said he had no recollection of it.

What conceivable logic could explain allowing loss-making companies to donate to political parties—if not to make room for shell companies that can be potential donors

What we do know is that the political parties were not consulted. A letter was sent to them in May 2017, three months after the scheme was passed by Parliament without discussion, asking them to suggest ways of improving it. Only four political parties wrote back opposing the scheme. The Congress pointed out that the electorate had a right to know the donor and the amount donated.

What is indisputable though is that the scheme has fundamentally changed Indian politics and democracy in the past five years of its existence. Not only has it undermined the authority of the ECI and impaired its ability to ensure free and fair elections on a level playing field, it has also diluted its powers of supervising and monitoring the funding of political parties. In sharp contrast to earlier practice, the Commission is completely in the dark regarding who is donating how much to which political party.

In November 2022, when the Union government unilaterally decided to open a fresh window for the sale of EBs ahead of the Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh elections, the ECI received the press communique while it was being “released almost simultaneously” by the PIB. Even though the model code of conduct had come into operation, it was not considered necessary to seek the ECI’s approval.

Electoral bonds have also warped Indian democracy by taking agency away from the voters. Whatever little influence Indian voters might have had earlier on stands taken by political parties, the selection of candidates, and so on, has now dwindled even further.

The scheme has also weakened state level regional leaders and donors. Political parties no longer need to look for donors among small and medium businessmen or individuals; nor depend on traditional fund-raisers and leaders in their states. Though purchased largely in five other cities, the centralisation of the scheme is evident with 80 per cent of the bonds being redeemed in Delhi.

Historian and author William Dalrymple wrote in his book The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company that this was possibly the first trading company to become a colonial power, with almost all of India being ‘effectively ruled from a boardroom in London’. Just as the Mughal empire was replaced by a ‘dangerously unregulated private company based overseas in a small office, five windows wide and answerable only to its shareholders’, electoral bonds seem to have ushered in a second ‘Company Raj’.

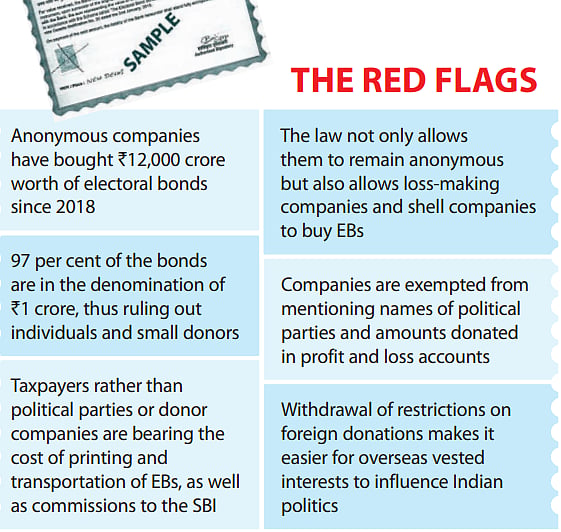

Prior to 2018, corporate funding of political parties was limited to a few hundred crores every year. In the last five years—despite the sharp decline in the sale of bonds during and after the pandemic— companies have purchased and disbursed almost Rs 12,000 crores worth of EBs. A whopping 80 per cent of this has gone to the BJP.

Naysayers may ask: how do we know the bonds were purchased by corporate entities? The tell-tale sign is this: the overwhelming majority of bonds sold are in the denomination of Rs 1 crore. As per information obtained from SBI by transparency activist Commodore Lokesh Batra (retd), 97 per cent of the bonds sold are of the highest denomination even though the same are available in denominations of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh and Rs 10 lakh. This clearly rules out individual buyers and small businessmen.

The scheme required amendments in the RBI Act, Income Tax Act, Companies Act, as well as in the Representation of People Act and the Foreign Contributions Regulation Act (FCRA). The amendment in the FCRA now allows foreign companies—and theoretically even governments and intelligence agencies—to donate to India’s political parties while remaining anonymous.

Political parties were exempted from the requirement of reporting the break-up of donations received through EBs to the Election Commission. The ECI, therefore, has no way of ascertaining whether government-owned companies and/or foreign sources have donated to political parties (earlier prohibited under Section 29B of the R.P. Act).

Amendments to the Companies Act removed the restriction that political donations could not exceed 7.5 per cent of the company’s net average profit in the preceding three financial years. The implication of this is that even newly incorporated companies can buy the bonds. Loss-making companies are allowed to make political donations and, theoretically, nothing prevents a company from transferring its entire share capital to a political party.

A new company’s entire share capital can now legitimately be ploughed into these bonds. How many of such shell companies have donated to political parties? We do not know.

Companies no longer have to declare details of political contributions in their profit and loss accounts naming the parties and the amounts donated to each. All that is mandatory is the total amount. What is completely absurd is that while anonymous cash donations of more than Rs 2,000 are prohibited, anonymous donations of a crore are not!

Speaking at a webinar hosted by the Association of Democratic Reforms recently, Dr Fuad Halim of the CPI(M) pointed out that electoral bonds have made it much easier for companies to deal directly and more brazenly with political parties. Direct negotiation enables companies to bargain for favourable deals and terms. With their anonymity and immunity being guaranteed by law, they can have no incentive to donate to the opposition. In short, he added, the scheme is designed to favour the ruling party.

And what is the logic for loss-making units being allowed (even encouraged) to donate to political parties? The barefaced intention seems to be to allow shell companies to be set up as potential donors. As the CPI(M) leader went on to say, nothing prevents shareholders from opening a company one day and handing over its entire share capital to a political party the next day.

The plot thickens when we realise that while the ECI and the public remain clueless, the money trail is accessible to the Union government and the SBI. The government knows which companies are donating to which parties. This skew gives the ruling party an unfair bargaining power over other political parties which it can browbeat or blackmail.

Venkatesh Nayak, director, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, explained how the scheme has robbed voters of their right to information, specifically their right to know about political funding. In 2016-17, political parties received 83 per cent of their donations from unnamed ‘other sources’.

Donations declared by all the national and recognised state parties totalled Rs 1,361 crore. Corporate donations amounted to just 10 per cent of the total. By 2019-20, however, electoral bonds constituted 69 per cent of the total donations. BJP alone in the last four years, ADR estimates, has received Rs 4,261 crore, six times more than the Congress, which received Rs 706 crore during the same period.

Unanswered questions abound. Why, for instance, did the ruling party overrule the RBI’s rightful claim that as central banker, it was its remit to issue currency-like promissory notes? Why was the suggestion that bonds should not be sold in physical form but only in digital form not accepted?

When the ECI protested that limiting bonds to recognised national and state parties who secured one per cent of the votes was discriminatory—as it denied access to independent candidates and new political parties—why was this objection overruled?

Also shrouded in mystery are the 105 sealed envelopes handed over to the Supreme Court in 2019 by the Election Commission. They supposedly contain details of the bonds received by political parties. Since the SBI is the sole entity that sells, redeems, and retains the amounts in special bank accounts, the court could have ordered the SBI to furnish the details, but it didn’t.

Curiously, in response to RTI applications filed by Batra, SBI asserted that only 24 political parties have been allotted special accounts to transact the proceeds of electoral bonds. In which case, how and why did 105 political parties submit details to the Election Commission?

Perhaps simply to lend credence to the government’s claim that anybody could buy electoral bonds and donate to any party of choice. With the SBI persisting in claiming confidentiality and its fiduciary relationship with the political parties, the veil of silence might well have stayed intact.

However, when the list was leaked and the Reporters’ Collective contacted some of the 105 parties, it became clear that most of them had not received a penny from electoral bonds. What they had done was participate in creating the impression that they had.

Shreegirish Jalihal of the Collective recalled that some of these political parties had unlikely names like ‘Asli Desi Party’ and ‘Hum Aur Aap Party’. One was even named ‘Sabse Badi Party’. One had no bank account. Another had a balance of Rs 700 in its account.

There couldn’t have been a more Machiavellian way of doing it.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines