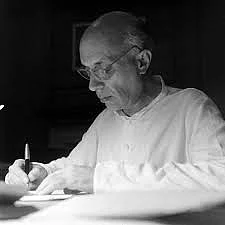

Nehru's Word: Continuity of Indian tradition and the Indian nationalism

In this extract Nehru tells us how his travels through India gave him an insight into the past; "To a somewhat bare intellectual understanding was added an emotional appreciation"

In the two preceding weeks, we brought to you examples of Jawaharlal Nehru’s deep and complex understanding of India which stands out in sharp contrast to the many contrived debates we witness today about the nature of the Indian nation and civilisation. This week, we bring to you another extract from ‘The Discovery of India’ in which he tells us how in his travels through the length and breadth of India, he visited old monuments, sculptures, frescoes, and went to the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad and Haridwar, and how through “these journeys and visits of mine…the land of my forefathers became peopled with living beings, who laughed and wept, loved and suffered….”.

---

I visited old monuments and ruins and ancient sculptures and frescoes — Ajanta, Ellora, the Elephanta Caves, and other places — and I also saw the lovely buildings of a later age in Agra and Delhi, where every stone told its story of India’s past. In my own city of Allahabad or in Haridwar I would go to the great bathing festivals, the Kumbh Mela, and see hundreds of thousands of people come, as their forebears had come for thousands of years from all over India, to bathe in the Ganges.

I would remember descriptions of these festivals written 1,300 years ago by Chinese pilgrims and others, and even then these melas were ancient and lost in an unknown antiquity. What was the tremendous faith, I wondered, that had drawn our people for untold generations to this famous river of India?

These journeys and visits of mine, with the background of my reading, gave me an insight into the past. To a somewhat bare intellectual understanding was added an emotional appreciation, and gradually a sense of reality began to creep into my mental picture of India, and the land of my forefathers became peopled with living beings, who laughed and wept, loved and suffered; and among them were men who seemed to know life and understand it, and out of their wisdom they had built a structure which gave India a cultural stability which lasted for thousands of years.

Hundreds of vivid pictures of this past filled my mind, and they would stand out as soon as I visited a particular place associated with them. At Sarnath, near Benares, I would almost see the Buddha preaching his first sermon, and some of his recorded words would come like a distant echo to me through 2,500 years.

Ashoka’s pillars of stone with their inscriptions would speak to me in their magnificent language and tell me of a man who, though an emperor, was greater than any king or emperor. At Fatehpur-Sikri, Akbar, forgetful of his empire, was seated holding converse and debate with the learned of all faiths, curious to learn something new and seeking an answer to the eternal problem of man.

Thus, slowly the long panorama of India’s history unfolded itself before me, with its ups and downs, its triumphs and defeats. There seemed to me something unique about the continuity of a cultural tradition through 5,000 years of history, of invasion and upheaval, a tradition which was widespread among the masses and powerfully influenced them. Only China has had such a continuity of tradition and cultural life.

And this panorama of the past gradually merged into the unhappy present, when India, for all her past greatness and stability, was a slave country, an appendage of Britain, and all over the world terrible and devastating war was raging and brutalizing humanity.

But that vision of 5,000 years gave me a new perspective, and the burden of the present seemed to grow lighter. The hundred and eighty years of British rule in India were just one of the unhappy interludes in her long story; she would find herself again; already the last page of this chapter was being written. The world also will survive the horror of today and build itself anew on fresh foundations.

My reaction to India thus was often an emotional one, conditioned and limited in many ways. It took the form of nationalism. For any subject country national freedom must be the first and dominant urge; for India, with her intense sense of individuality and a past heritage, it was doubly so.

Recent events all over the world have demonstrated that the notion that nationalism is fading away before the impact of internationalism and proletarian movements has little truth. It is still one of the most powerful urges that move a people, and round it cluster sentiments and traditions and a sense of common living and common purpose.

While the intellectual strata of the middle classes were gradually moving away from nationalism, or so they thought, labour and proletarian movements, deliberately based on internationalism, were drifting towards nationalism.

The coming of war swept everybody everywhere into the net of nationalism… The nationalist ideal is deep and strong; it is not a thing of the past with no future significance. But other ideals, more based on the ineluctable facts of today have arisen, the international ideal and the proletarian ideal, and there must be some kind of fusion between these various ideals if we are to have a world equilibrium and a lessening of conflict.

The abiding appeal of nationalism to the spirit of man has to be recognised and provided for, but its sway limited to a narrower sphere.

If nationalism is still so universal in its influence, even in countries powerfully affected by new ideas and international forces, how much more must it dominate the mind of India. Sometimes we are told that our nationalism is a sign of our backwardness and even our demand for independence indicates our narrow-mindedness.

Those who tell us so seem to imagine that true internationalism would triumph if we agreed to remain as junior partners in the British Empire or Commonwealth of Nations.

They do not appear to realise that this particular type of so-called internationalism is only an extension of a narrow British nationalism, which could not have appealed to us even if the logical consequences of Anglo-Indian history had not utterly rooted out its possibility from our minds.

Nevertheless, India, for all her intense nationalistic fervour, has gone further than many nations in her acceptance of real internationalism and the co-ordination, and even to some extent the subordination, of the independent nation state to a world organisation.”

(Selected and edited by Mridula Mukherjee, former Professor of History at JNU and former Director of Nehru Memorial Museum & Library)

(This was first published in National Herald on Sunday)

Also Read: Nehru's Word: The panorama of India’s past

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines