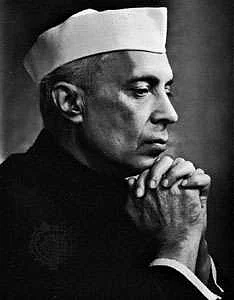

Nehru’s Word: Profit for some meant death for others

'The Famine Inquiry Commission, reveal in restrained official language, the tragic succession of official errors and private greed which led to the Bengal famine'

Continuing from last week Jawaharlal Nehru’s scathing critique of the acts of omission and commission of the then Government of India which led to the Bengal Famine, a critique which resonates loudly with the contemporary crisis facing us today.

“Estimates of the number of deaths by famine in Bengal in 1943-44 vary greatly. The Department of Anthropology of the Calcutta University carried out an extensive scientific survey of sample groups in the famine areas. They arrived at the figure of about 3,400,000 total deaths by famine in Bengal….The official Famine Inquiry Commission, presided over by Sir John Woodhead, has come to the conclusion that about 1,500,000 deaths… occurred.

“The Famine Inquiry Commission, presided over by Sir John Woodhead (Report published in May 1945), reveal in restrained official language, the tragic succession of official errors and private greed which led to the Bengal famine. ‘A million and a half of the poor of Bengal fell victim to circumstances for which they themselves were not responsible. Society, together with its organs, failed to protect its weaker members. Indeed, there was a moral and social breakdown, as well as administrative breakdowns.’ They refer … to the fact that a considerable section of the population was living on the margin of subsistence and was incapable of standing any severe economic stress, to the very bad health conditions and low standards of nutrition, to the absence of a ‘margin of safety’ as regards either health or wealth….

“They condemn the policy, or often the lack of policy or the ever-changing policy, of both the Government of India and of the Bengal Government; their inability to think ahead and provide for coming events; their refusal to recognise and declare famine even when it had come; then totally inadequate measures to meet the situation. They go on to say: ‘But often considering all the circumstances, we cannot avoid the conclusion that it lay in the power of the Government of Bengal, by bold, resolute and well-conceived measures at the right time to have largely prevented the tragedy of the famine as it actually took place.

"Further, that the Government of India failed to recognise at a sufficiently early date, the need for a system of planned movement of food grains….The Government of India must share with the Bengal Government responsibility for the decision to decontrol in March 1943....The subsequent proposal of the Government of India to introduce free trade throughout the greater part of India was quite unjustified and should not have been put forward. Its application, successfully resisted by many of the provinces and states… might have led to serious catastrophies in various parts of India.’

“After referring to the apathy and mismanagement of the governmental apparatus both at the centre and in the province, the Commission say that ‘the public in Bengal, or at least certain sections of it, have also their share of blame. We have referred to the atmosphere of fear and greed which, in the absence of control, was one of the causes of the rapid rise in the price level. Enormous profits were made out of the calamity, and in the circumstances profits for some meant death for others. A large part of the community lived in plenty while others starved, and there was much indifference in face of suffering. Corruption was widespread throughout the province and in many classes of society.’

“While all this was happening and the streets of Calcutta were strewn with corpses, the social life of the upper ten thousand of Calcutta underwent no change. There was dancing and feasting and a flaunting of luxury, and life was gay. There was no rationing even till a much later period. The horse races in Calcutta continued and attracted their usual fashionable throngs. Transport was lacking for food, but racehorses came in special boxes by rail from other parts of the country. In this gay life both Englishmen and Indians took part for both had prospered in the business of war and money was plentiful. Sometimes that money had been gained by profiteering in the very foodstuffs, the lack of which was killing tens of thousands daily.

“India, it is often said, is a land of contrasts, of some very rich and many very poor, of modernism and medievalism, of rulers and ruled, of the British and Indians. Never before had these contrasts been so much in evidence as in the city of Calcutta during those terrible months of famine in the latter half of 1943. The two worlds, normally living apart, almost ignorant of each other, were suddenly brought physically together and existed side by side. The contrast was startling, but even more startling was the fact that many people did not realise the horror and astonishing incongruity of it and continued to function in their old grooves. What they felt one cannot say; one can only judge them by their actions. For most Englishmen this was perhaps easier for they had lived their life apart and, caste-bound as they were, they could not vary their old routine, even if some individuals felt the urge to do so. But those Indians who functioned in this way showed the wide gulf that separated them from their own people, which no considerations even of decency and humanity could bridge.

“The famine, like every great crisis, brought out both the good qualities and the failings of the Indian people. Large numbers of them, including the most vital elements, were in prison and unable to help in any way. Still the relief works organised unofficially drew men and women from every class who laboured hard under discouraging circumstances, displaying ability, the spirit of mutual help and co-operation and self-sacrifice. The failings were also evident in those who were too full of their petty rivalries and jealousies to co-operate together, those who remained passive and did nothing to help others, and those few who were so denationalised and dehumanised as to care little for what was happening.”

(Selected and edited by Mridula Mukherjee, former Professor of History at JNU and former Director of Nehru Memorial Museum and Library)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines