Noakhali: Where Gandhi waged the battle for India

While Hindu Mahasabha clamoured for military to be sent to quell riots, the one man army of Mahatma Gandhi, 77, moved from village to village, admonishing Muslims and calling upon Hindus to fight back

Gandhi in Noakhali (1946-1947)

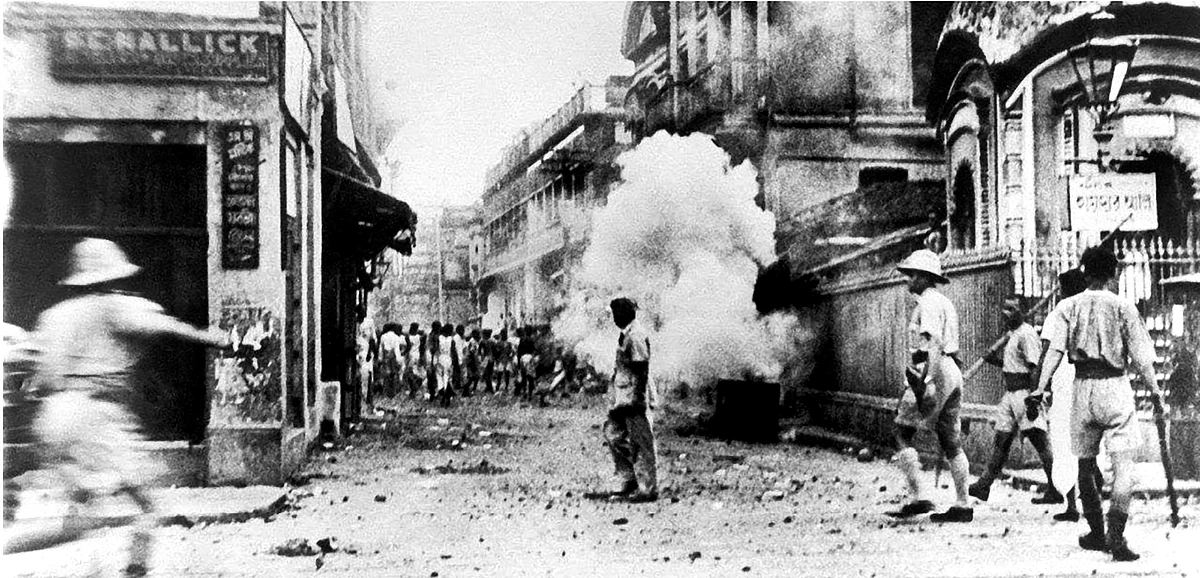

Six weeks after the bloodiest communal violence in pre-partition India, the Calcutta killings, which began on 16th August, 1946, and continued for the next four to five days in an intense form, killing more than 5000 people, violence erupted in the villages of Bengal’s Noakhali district.

Tucked far away in Bengal’s easternmost corner, the rural landscape of Noakhali (and Tipperah), and the villages around witnessed violence of an intensity that was repeated a couple of months later in Punjab.

In Noakhali, the rioting not only left a large number of Hindus dead, while others fled, it also sought to obliterate symbols and forms of religious and cultural lives of the minority population.

A large number of them were forcibly converted and married.

Sensing that this was a new phase of communal violence, Gandhi found Noakhali beckoning him, for it had thrown up issues which pertained not to Bengal alone.

“The battle for India” he mused, “is today being decided in East Bengal.” Articulating what he thought was the prevailing mood there, he said: “Mussulmans are being taught by some that Hindu religion is an abomination”. He wanted to combat such ideas which he thought would destroy India and the Indian people.

***********

Gandhi was in Noakhali and Tipperah districts from 6th November, 1946, and he stayed there till the end of February, 1947.

His visits to the villages stirred the entire area with new life, provided succour to the violated humanity and provided people outside Noakhali a sense of relief in having someone of Gandhi’s stature there in those trying circumstances.

Today, after almost 73 years, those lonely furrows of Gandhi remain with us as the only blueprint of how to combat the situation when communalism and communal violence grip the human mind in a deadly bind.

On reading various accounts of his trying times there, it appears that there were three essential counters to the communal sway that Gandhi propagated: ‘fearlessness’ to those being attacked, responsibility to those perpetrating the attacks, and finally, the lack of ethical and moral legitimacy to communal ideology of any hue.

Invocation of Fearlessness

In Noakhali villages, he met hapless people, molested women and Hindu families still in hiding, primarily the poor, as most of the rich families, who were not killed, had fled their villages. Gandhi invoked fearlessness.

While Hindu Mahasabha leaders sitting in Calcutta and outside Bengal were demanding military protection for the besieged population, Gandhi was a one-man military. He walked door-to-door and village-to-village, comforting and giving the hapless courage.

His visits were resented by the Muslims League ministers, Muslim League workers, the local Maulvis and even a large number of common Muslim villagers under complete communal sway. The massacre of Muslims in Bihar as a reaction to Noakhali was also used to protest his visit to Noakhali, and he was asked by none less than the Chief Minister of Bengal, Suhrawardy himself, to leave.

The villagers threw night soil on the narrow and slippery village path, they dug up the narrow waterlogged roads so that he could not walk. And yet Gandhi, a frail man, 77 years of age, was determined.

He answered his detractors by walking barefoot, sending away his companions, sleeping every night in a different village, taxing his body even more, as if challenging them to do their maximum but it would not deter him. Not only that he himself showed no fear, but he told people to shed their fears and to confront the perpetrators of violence.

‘No police or military would protect those who are cowards’. He was particularly angry at the way the male population of many villages ran away leaving their mothers, wives, sisters and daughters to confront the molesters. In the same manner, he chastised the so called upper-caste leaders, questioning their right to speak as leaders when they themselves ran away leaving the lower caste vulnerable people.

He wanted people not to depend on others but to have faith in themselves in such a situation, and if they had none, to “remember God”.

Thus, when a peace worker asked his views on the rehabilitation of the people there, he answered that it is not by sending them to Assam and West Bengal that one would rehabilitate them. It was to be done by infusing “courage in them so that they are not afraid to stay in their original homes.” Was it possible, people wondered? For Gandhi, it was eminently doable.

His invocation to the workers was that they should stay with the villagers and assure them that “they will die to the last person before a hair of your head is injured.’ Such infusion would produce, as he said: “heroines in East Bengal.”

The result was magical and electrifying. The women in the villages experienced a new lease of life and in fact told Gandhi that you have “opened up a new vista before us, Mahatmaji. We feel fresh blood coursing through our veins” (Harijan, 8.12.1946).

He saw forcible marriage and forcible conversion also in the light of the attempt to scare people. On 12 November at Dattapara, he said that he ‘had seen the terror-stricken faces of the sufferers.’ They had been forcibly converted once and they were afraid the same thing would be repeated. He knew that the communal ideology wins by instilling fear and therefore he attacked the atmosphere of fear.

There were, however, those like the Hindu Mahasabha and other leaders in Calcutta, who demanded military protection when after the Calcutta killings it was perfectly clear that the British had decided to allow the Indians to stew in their own juice and would not intervene in any meaningful way.

Gandhi, on the other hand was on the field like an army commander. He declared to the Hindu Mahasabha delegation that contrary to latter’s idea of him being impractical, he was in fact “a practical idealist.”

He saw what the Hindu Mahasabha leaders were refusing to see – that any talk of army protection would make the Muslim villagers more belligerent against the Hindus still living there. This would also hamper the return of a normal social existence in these villages. The partition riots of Punjab a couple of months later was to prove him correct. Even the military presence in Punjab did nothing to lessen the killings. In fact, he possibly saved the Bengalis from a sure blood bath.

The Idea of Responsibility

Along with facing the situation boldly, Gandhi realised it was also important that the Hindus should continue to live in those remote villages. If one magnifies this to the scale of the nation and the idea of Pakistan, Gandhi’s counter was to attack the lack of belief in common living, a common history and a common destiny.

In Noakhali, Gandhi’s efforts took the shape of infusing the idea of responsibility among the Muslims, to ensure that the social rupture is mended and people returned to their shared lives. For him, the Muslims and Hindus needed to live together in the land of their ancestors, but not with military or police protection or depending upon the mercy of those who had brute demographic power. Gandhi made this very clear from the beginning.

On 10th November, 1946, he said, “It has been said that the Hindus and Mussalmans cannot stay together as friends or co-operate with each other. No one can make me believe that, but if that is your belief, you should say so. I would in that case not ask the Hindus to return to their homes. They would leave East Bengal, and it would be a shame for both the Mussalmans and the Hindus. If, on the other hand, you want the Hindus to stay in your midst, you should tell them that they need not look to the military for protection but to their Muslim brethren instead. Their daughters and sisters and mothers are your own daughters, sisters and mothers and you should protect them with your lives.”

This was central to his battle against the very idea that the Hindus and Muslims cannot live together, and that a separate Pakistan and Hindustan was required for the separated communities.

He argued that in case there is a Pakistan, the people have to assure that there is safe place for Hindus there. The responsibility, therefore, was with the Muslim villagers to show this by owning up responsibility of their Hindu neighbours, and of the government of S.H. Suhrawardy for the Hindu population of the province.

If one accepted that the Hindus should be migrating to safe places or that the military protects them in their villages, then, for Gandhi, the case was lost. In such cases, he would not hesitate in asking for a complete transfer of population. It is in this context that he stated he did not want to be ‘a willing party to Pakistan’.

Moral and Ethical Critique

Gandhi saw the intensity of religious intol¬erance in the Noakhali villages which convinced him that communalism is denial of the higher ethical and moral values that religion preaches.

When he visited Masimpur on 7th January, 1947, the Muslim audience left the place once he began his prayer meeting. ‘I am sorry’ Gandhi publicly said, ‘because some of my friends had not been able to bear any name of God except Khuda but I am glad because they have had the courage of expressing their dis¬sent openly and plainly.’

Gandhi’s response to this aspect of communal ideology was also the assertion of the moral right of every individual to profess or follow any religion as long as it did not negatively affect the others' religious creed.

Taking the discussion to the ethical core of religion, he appealed to the ‘Muslim brethren’ to assure him ‘of that freedom which is true to the noblest tradition of Islam.’ He showed, contrary to the Hindu Mahasabha campaign maligning him later, no sense of appeasing the Muslim leaders or preachers, or even the villagers. Rather he took them on directly as none had ever done in public for their pettiness and communal beliefs.

His stout defence of his Ram dhun and the prayer meetings testified to his fight for religious freedom. The prayer meetings in the open not only brought people, particularly womenfolk, into the open, which they were scared to do, but also prepared them to shed their fear.

Gandhi was more than a leader for the people of Noakhali; he was seen as the liberator of the Hindus. In a place where all symbols of a particular reli¬gion had been made the target of attack, the Gandhian defence came as an attack on that particular undercurrent of communal ideology, which legitimised intolerance and narrow political ideas in the name of religion.

He also confronted the religious men who legitimised religious violence by giving it a religious cloak. They were the men who performed conversions, read the Kalama out to the scared and hapless people, and solemnised forced marriages.

Gandhi met one such leading preceptor, Maulvi Khalilur Rahman of Devipur on 17th February, 1947. He was reportedly responsible for the conversion of a large number of Hindus during the disturbances, and asked him why did he do it. On hearing the response that these conversions should not be taken seriously as these were done to save lives, Gandhi became furious at this casual approach to religion.

He, in fact, retorted by saying, as his secretary in those fateful days, N.K. Bose reported, that as a religious preceptor he would have done better to have taught ‘the Hindus to lay down their lives for their faith, rather than give it up through fear.’ He in fact went to the extent of saying that if he ‘ever he met God, he would ask Him why a man with such views had ever been made a religious precep¬tor’.

This and other encounters made him realise that the acts of communal violence and attacks on religion during the riot had the strong sanction of the clerics and religious teachers. He then tried to deprive the communal ideology of its political and religious legitimacy.

He invoked higher authorities, i.e., Jinnah, Quran, etc., to raise the Muslim villagers to some ethical and moral plane. His constant references to the Quran were also supportive of his argument that ‘if people had known the true meaning of their scriptures, happenings like those of Noakhali could never have taken place’.

In a talk with the villagers of Fatehpur, he appealed to their reason by saying: “ It is the easiest thing to harass the Hindus here, as you Muslims are in the majority. But is it just as honourable? Show me, please, if such a mean action is suggested anywhere in your Koran. I am a student of the Koran...So, in all humility I appeal to you to dissuade your people from committing such crimes, so that your own future may be bright.

For Gandhi, the social partition needed to be prevented even if the political partition seemed inevitable. Noakhali was the field where he sought to fight communalism in its new avatar.

If he prepared his mass struggle in the laboratory of Bardoli, Noakhali was the laboratory for his future battle against communalism. For Gandhi, communalism had always been a question seen from the perspective of ‘Hindu-Muslim separation’, rather than as a complex phenomenon, namely ideology.

It is here for the first time that one sees him conceptualizing the ideological battle. Before he could develop his understanding further, he was killed in January 1948, by the very same communal forces he was fighting with all his might. Had he lived longer, he would have brought a definitive critical insight into the ways to understand communal ideology, and the means to fight it too.

(Rakesh Batabyal is a historian of Modern India who teaches at JNU. He has published widely, including his seminal work, Communalism in Bengal).

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines