Those who still question the enduring legacy of the Nehru-Gandhi family should read VS Naipaul

The Nehru-Gandhi family has given India three Prime Ministers. It is without a parallel. But the sacrifice made by this family in the service of the nation is also without parallel

Several people will undoubtedly record the contributions of Nehru and Indira Gandhi and of their sacrifice for the nation on their birth anniversaries which fall within the span of a week on 14th and 19th November respectively. A recent lead article by Zafar Agha (Dynasties Do Rule Democracies, National Herald, October 24, 2021) made one marvel again at the sway the Nehru-Gandhi family has held over public imagination for nearly a century.

Although Jawaharlal Nehru had met Gandhi in December 1916 at a meeting of the Indian National Congress at Lucknow, the story can be taken to have begun on December 7, 1921 with Motilal Nehru facing a trial at Naini Jail, for leading a hartal against the visit of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) to Allahabad. Indira, then four-year old, was present in the court room with her grandfather, watching this whole spectacle. It was her initiation into public life.

The Nehru-Gandhi family has given India three Prime Ministers. It is without a parallel anywhere in the world. But the sacrifice made by this family in the service of the nation is without parallel too. Indira Gandhi and her son Rajiv Gandhi, both died a martyr’s death at the hands of assassins.

Nehru, urbane and an aristocrat to the bone, often referred to as the ‘last Mughal’, charted the course of India’s history as a truly independent nation. The Congress government under him at the centre and those headed by the Congress chief ministers held sway over nearly whole of India under him for nearly seventeen years. It was three years after him that the UF Government in West Bengal and the Communist Government in Kerala came to power in 1967.

Nehru’s reputation as a democrat preceded him wherever he went. In the Foreword to the American edition of his autobiography, Toward Freedom, published seven years before India’s independence, Richard J. Walsh recorded: "Nehru today is the great democrat of the world. Not Churchill, not Roosevelt, not Chiang Kaishek, in a sense not even Gandhi stands as firm as Nehru does for government by the consent of the people and for the integrity of the individual. He scorns and despises Nazism and fascism."

He was not a Communist, he explained, ‘chiefly because I resist the communist tendency to treat communism as a holy doctrine. I feel also that too much violence is associated with communist methods.’ The goal of India, as he stated it, was ‘a united democratic country, closely associated in a free world federation of democratic nations.’ This briefly sums up the political vision of Nehru.

During his maiden visit to the United States in 1949, Nehru was idolised by Hollywood directors and movie stars and wooed by America’s big business. Yet he did not let the might of America’s wealth and her charm affect him.

Dom Moraes, in his biography of Indira Gandhi recalled hearing an anecdotal account. ‘On a visit to New York, Nehru was the guest of honour at a lunch in Wall Street where several of the richest men in America were present. “Just think, Mr Prime Minister,” said his host, “at this very moment you are lunching with men worth 40 billion dollars”.

It was apparently difficult for his aides to persuade Nehru not to throw down his napkin and walk out!’ Dom mentioned this story to Indira and asked if she had been there and if the story was apocryphal or true. She laughed a little but did not answer directly. ‘Well, the Americans irritated my father. But that was because of his British education’. (Dom Moraes, Indira Gandhi, pages 133-134)

In an article on Indira Gandhi after her death, Norman Cousins, titled, India: Carrying on the Nehru tradition, wrote, ‘After Nehru’s death’, ‘there was deterioration on the home front. The country needed a rallying centre… Jawaharlal Nehru had inherited the mantle of Mahatma Gandhi; now it was necessary to pass along the mantle and the full symbolic power of the Nehru name in providing continuity for the total society. Indira possessed this symbolism’. (The Christian Science Monitor, November 14, 1984).

Similar views were echoed by V.S. Naipaul, mingling praise for both Nehru and Indira, in an article written for The Daily Mail, which was also reprinted by the New York Times on 3rd November 1984, three days after Indira’s death. The Nobel Laureate wrote: Indira gave India stability; without her, that ceases to exist. The country has grown intellectually and industrially, and for a long time there has been a balance between rationalism, the life of the mind and the pull of barbarism.

‘India has been very lucky in the Nehru family’, he further wrote, ‘Nehru was unique in recent world history: a colonial protest figure, a folk hero who did not appeal to fanaticism but was a reasonable, reasoning man. A man committed to science, religious tolerance, the rule of law and the rights of man. Indira Gandhi his daughter carried on this way of looking at things’.

Naipaul defended Indira’s decision to declare Emergency. ‘You can easily make out a case for her being authoritarian, antidemocratic, stamping out protest’, he said in the same piece. ‘But it isn’t enough to do that. One must consider what was the other side. In 1975 some opposition parties wanted India to go back to some preindustrial time of village life. Piety can take odd forms. In 1971 election, in a desert constituency, one candidate was bitterly opposed to bringing piped water to villages- “Un-Gandhian, un-Indian, damaging to the morality of Indian women...”

'Others wanted to combine the worst of the Holy Cow outlook with the making the nuclear bomb. There were innumerable cults. I was on her side at the time- not because she was authoritarian, but because I felt that while she was there, education and science had a chance of continuing’.

One is inclined to quote more from the piece. ‘The achievement of the Nehrus has been fabulous: under them India got its industrial revolution and with that came the intellectual revolution. Indians, more than they acknowledge, owe a lot to the stability that Mrs. Gandhi, following her father, created. Three or four generations have been permitted to flourish, thanks to that balance.

With pronouncements such as hard work mattered more than Harvard, with the weird claim that fumes arising from burning cow dung can cure Covid infection and the arrest of people for cheering Pakistan’s cricket team, do we not see that balance between the ‘life of the mind and barbarism’ tilting towards barbarism?

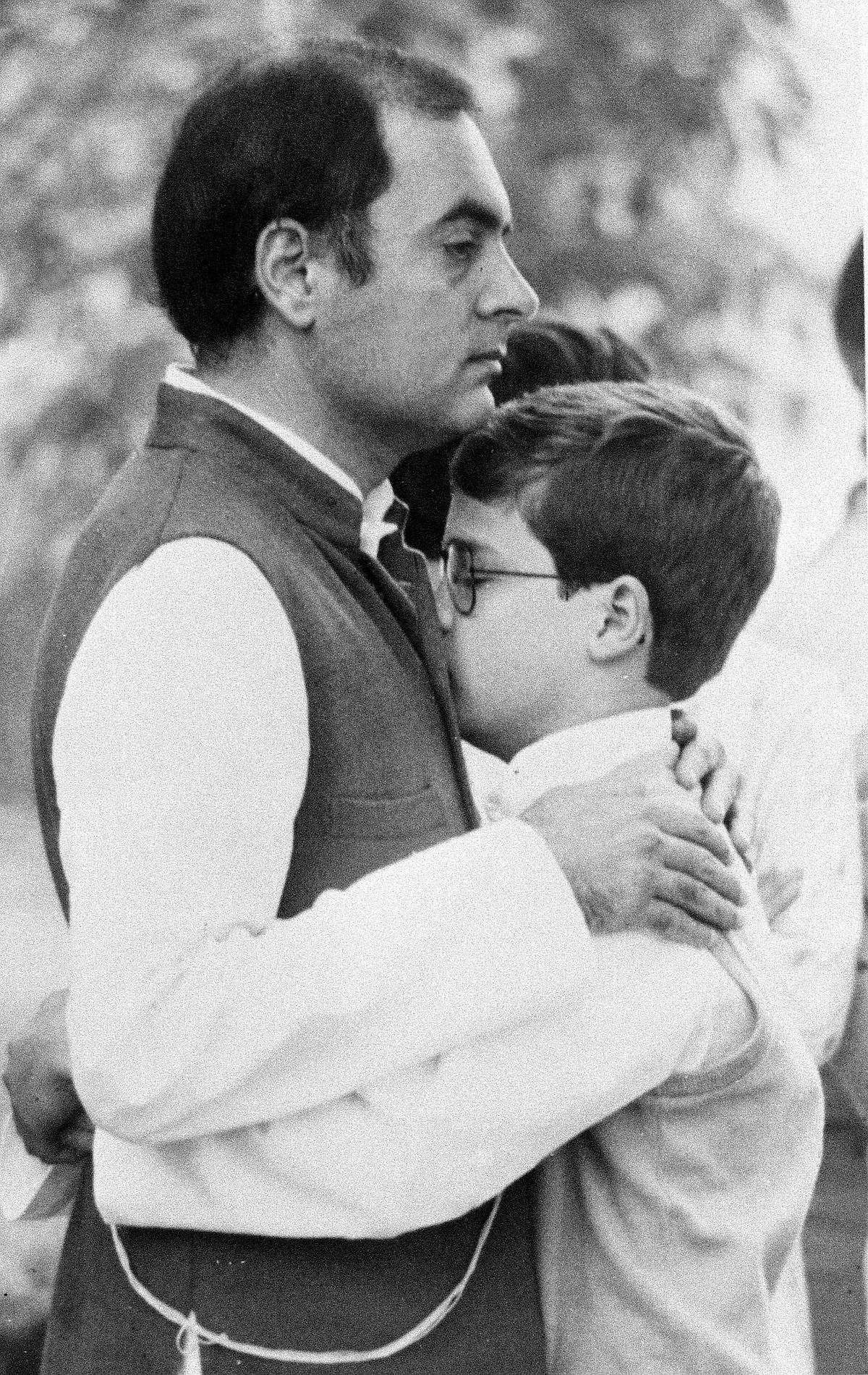

I remember another full-page article written by V.S. Naipaul for the Illustrated Weekly of India, in the aftermath of Indira’s tragic assassination. In that piece, Naipaul dwelt on the charisma of the Nehru- Gandhi family that held sway over the Indians for nearly three generations and before which, he said, the Kennedys pale into insignificance. In between the columns of that write-up, the page carried an image of the 12- year-old Priyanka rising like a Phoenix from the flames of Indira’s funeral pyre. The point the great writer wanted to make was abundantly clear.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines