‘Where will we go, leaving everything behind?’

At the site of the Deocha Pachami coal mine in West Bengal, women fight a vain battle to hold on to their land, to not lose their livelihoods

“Ei gachh, ei ghor, ei matir je maya, sei maya liye amra kuthay jabo? (This tree… this house… the tenderness this soil carries… Where can we go, with this love?)”

Apankuri Hembram is both sad and angry. “All this is mine,” says the Santhal Adivasi woman, her eyes sweeping around. “I have my own land,” adds the 40-year-old, pointing from one marker to another on the land. Her five–six bighas (roughly one-and-a-half acres) of land is used to cultivate paddy.

“Will the government be able to give all that I have built over these years?”

The Deocha Pachami (also spelt Deucha Pachmi) state coal mining project in West Bengal’s Birbhum district is slated to wipe out 10 villages, including Apankuri’s Harinsinga.

“Where will we go leaving everything behind? We will not go anywhere,” Apankuri adds firmly. She is among those at the forefront of the protest against the mine. Women like her are organising meetings and marches, taking on the combined might of the police and the ruling party—armed with kitchen and farm implements like sticks, brooms, sickles and kataris (machete-like choppers).

The winter afternoon sun is shining brightly in Harinsinga village. Apankuri is speaking to us standing in the courtyard of her neighbour Labsa’s house, with its brick rooms and tiled roof, located at the entrance to the village.

“They have to take our lives for our land,” says Labsa Hembram, joining the discussion as she also catches up on lunch—a mix of rice and water with leftover vegetables, cooked last night. Labsa, also 40 years old, works in the crusher, the place where the stones are broken up. Daily wages at the crusher range between Rs 200 and Rs 500.

The majority of the population of Harinsinga are Adivasis. There are also Dalit Hindus and upper-caste migrant labourers who came from Odisha many years ago.

The land that belongs to Apankuri, Labsa and others lies above the massive Deocha–Pachami–Dewanganj–Harinsingha coal block. Under the aegis of the West Bengal Power Development Corporation, this soon-to-be-live open-cast coal mine will be the largest in Asia and the second largest in the world—covering 12.31 square kilometres or 3,400 acres, according to the district administration.

The mining project will swallow up land in Hatgachha, Makdumnagar, Bahadurganj, Harinsinga, Chanda, Saluka, Dewanganj, Alinagar, Kabilnagar and Mouza Nischinta-pur in Birbhum district’s Mohammad Bazar block. The women are part of Deocha Pachami’s anti-mining people’s movement here. “We [the village] are united this time,” says Labsa. “This piece of land will not go to some outsider. We will protect it with our hearts.”

The project will render thousands of residents like them homeless and landless, not ‘bathe West Bengal in the light of development for the next 100 years’, as officials are claiming.

Darkness looms large beneath the ‘light’. Perhaps as congealed as coal itself. This project will have a devastating impact on the environment.

In a statement published in December 2021 protesting against the mine, some eminent persons of West Bengal, including environmentalists and environmental activists, raised this concern. The statement says, ‘In open-pit coal mines, the topsoil created over millions of years is permanently lost and turned into mounds of waste.

Not just landslides, the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems suffer massive damage. During the monsoons, the waste mounds are washed away and deposited at the bottom of the rivers in the area, causing unintended floods[…] disrupting the flow of groundwater not only in the area, but it also adversely impacts the agricultural–forestry production and damages the ecological balance of the entire region.’

The protesting women are also relying on the dhamsa and madal. Not just musical instruments, the dhamsa and madal are intrinsically lin ked to the struggles of the Adivasi community. To the beat of these symbols of their life and resistance is mixed with the tune of their slogan that rings out: “Abuya disam, abuya raaj (Our land, our rule).”

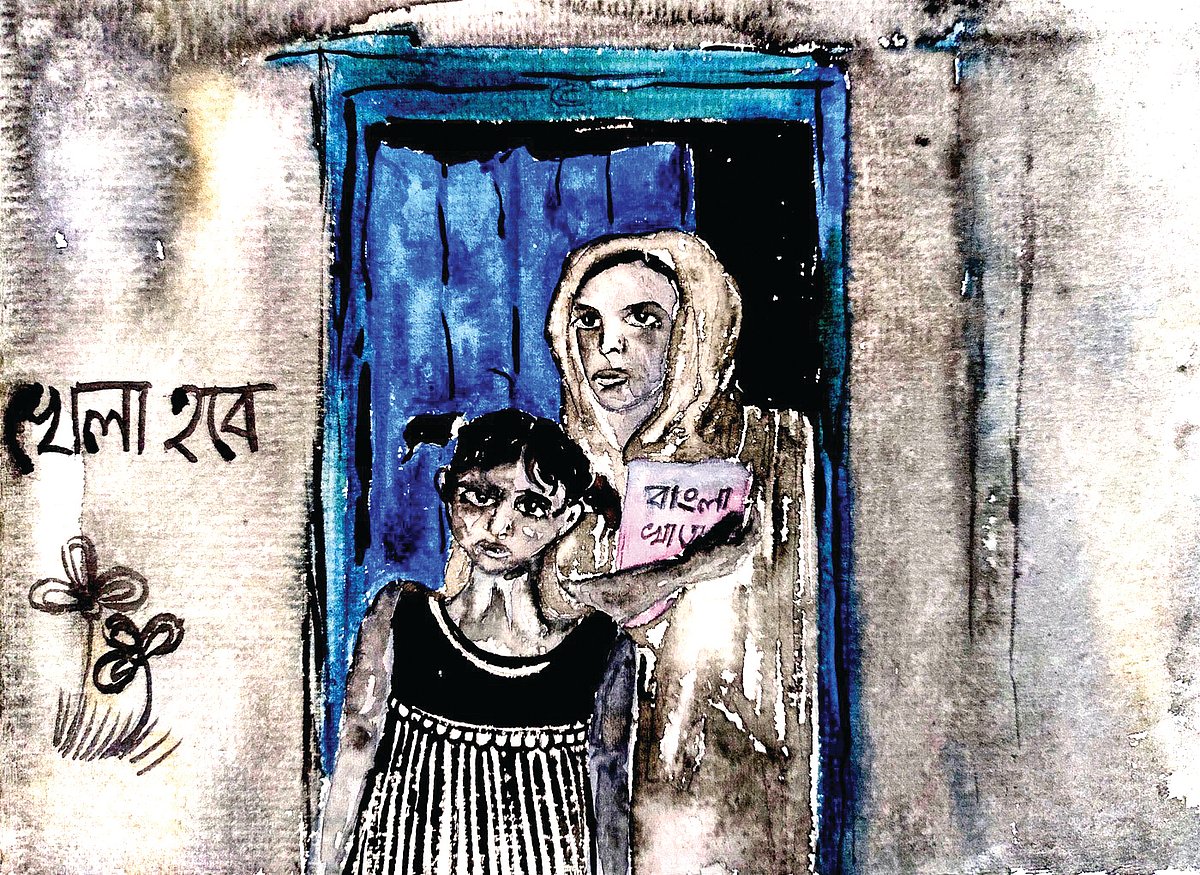

In solidarity with the women and others who are fighting, I visited Deocha Pachami and created these illustrations. I listened to them speak about the promises made by the government—housing for all, metalled roads in the rehabilitation colony, potable water, electricity, health centre, school, transportation and more.

It is ironic that what should be basic rights after so many years of Independence is now being used as a bargaining tool.

Those people who are determined not to part with their land have assembled under the umbrella of Birbhum Jameen, Jiban, Jibika, Prakriti Bachao (save the land, life, livelihood and nature) Mahasabha. Many individuals and organisations from urban areas are also visiting Deocha to stand with the people fighting against land acquisition, such as the CPIM(L), the Jai Kisan Andolan and human rights organisation Ekusher Daak (Call of the 21).

“Go, and show this picture to your government,” said Sushila Raut, a resident of Harinsinga, pointing towards her makeshift toilet made from torn tarpaulin sheets.

About an hour’s walk from here is the village of Dewanganj, where we meet Husnaara, a student of Class 8. “For all these days the government did not think of us. Now they are saying, there’s a lot of coal under our homes. Where will we go, leaving all this behind?” asks the student of Deocha Gaurangini High School.

It takes a total of three hours for her to travel to school and back. She points out that the government has failed to build a single primary school in her village, let alone a high school. “I feel lonely when I go to school, but I haven’t quit studying,” she says. Many of her friends dropped out of school during the lockdown. “Now there are outsiders and policemen on the streets so my family members are scared, and I can’t go to school.”

Husnaara’s grandmother Lalbanu Bibi and mother Mina Bibi are threshing rice in their courtyard with Antuma Bibi and other women from the neighbourhood. In winters, the women of the village make flour from this rice and sell it. Antuma Bibi says, “In our Dewanganj, there is neither good roads, nor a school, nor a hospital. If someone falls sick, we have to rush to Deocha. Have you ever come to find out how difficult it is here for pregnant girls? Now the government is talking about development. What development?”

Antuma Bibi also informs us that it takes about an hour to get to the Deocha hospital from Dewanganj. The nearest primary healthcare centre is in Pachami. Or one has to go to the government hospital in Mohammad Bazar. It takes an hour to reach that hospital as well. If the issue is serious, they have to go to the hospital in Suri.

Their husbands all work in the stone quarries and earn daily wages of around Rs 500–600. The family subsists on this income. According to government sources, there are around 3,000 quarry and crusher workers in the mining area, who will need to be compensated for the loss of land.

The women of the village are worried that if they are displaced from the village, their source of income from stone-crushing will also cease to exist. They are suspicious about the government’s promise of a job. There are many educated men and women in this village who have no jobs.

Tanzila Bibi is drying paddy and wields a stick in her hands to chase off nosy goats. When she sees us, she runs towards us with the stick in her hands. “You will hear one thing and write another. Why do you come to play such games with us? I’m telling you, I won’t leave my home, and that is final. They’re sending the police to make our lives hell. Now they are sending journalists every day.” Raising her voice, she adds, “We have only one thing to say, we will not give up our land.”

From 2021 to 2022, many of the women I met on my visits were taking part in the fight for land rights. Since then, the movement has lost much of its momentum, but these voices of resistance remain strong. These women and girls continue to speak against oppression and exploitation. Their roar for justice will forever resound, for jal, jangal, jameen (water, forest, land).

(Labani Jangi is a 2020 PARI fellow, and a self-taught painter based in West Bengal’s Nadia district. This article was first published by the People’s Archive of Rural India [PARI])

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines