Concerns of Jawaharlal Nehru during the first General election in 1952

Jawaharlal Nehru’s commitment to parliamentary democracy is shown by the seriousness with which he treated the business of elections.

As we observe Jawaharlal Nehru’s 55th death anniversary, our thoughts invariably go back at the end of this election season to the first general elections conducted under Nehru’s watch in 1951-52.

In Nehru’s understanding, democracy was necessary for keeping India united as a nation. Given its diversity, it could only be held together by a non-violent, democratic way of life, and not by force or coercion. Only a democratic structure which gave space to various cultural, political, and socio-economic trends to express themselves could hold India together.

“This is too large a country with too many legitimate diversities to permit any so-called ‘strong man’ to trample over people and their ideas.”

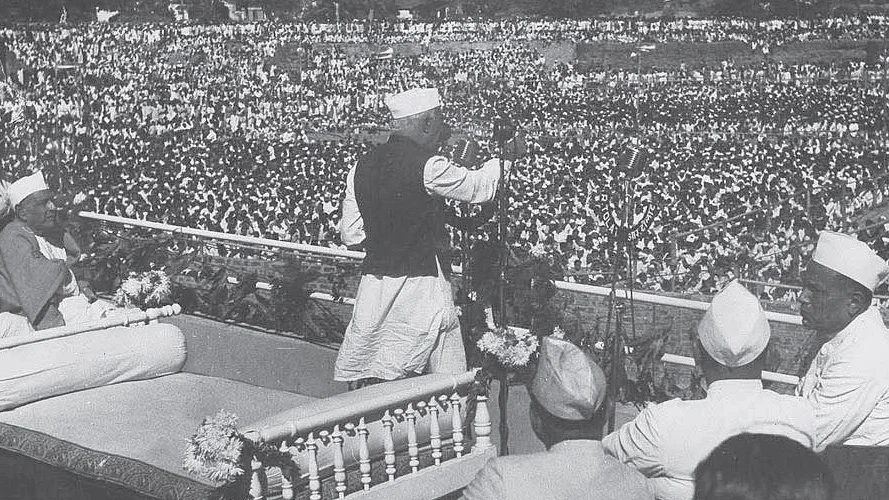

In the election campaign for the first General Elections of 1951-52, Nehru travelled some 25,000 miles and addressed in all about 35 million people or a tenth of India’s population.

In this exercise, over a million officials were involved. 173 million voters were registered through a house-to-house survey. Three-quarters of those eligible were illiterate. Elections were spread out over six months, from October 1951 to March 1952, and candidates of 77 political parties, apart from some independents, contested in 3,772 constituencies. All observers, Indian and foreign, were agreed that it was fair.

The Manchester Guardian wrote on 2 February 1952: “The Working Committee of the Indian National Congress can draw pleasure from the extraordinary demonstration which India has given. If ever a country took a leap in the dark towards democracy, it was India. Contemplating these facts, the Congress Working Committee may purr with satisfaction.”

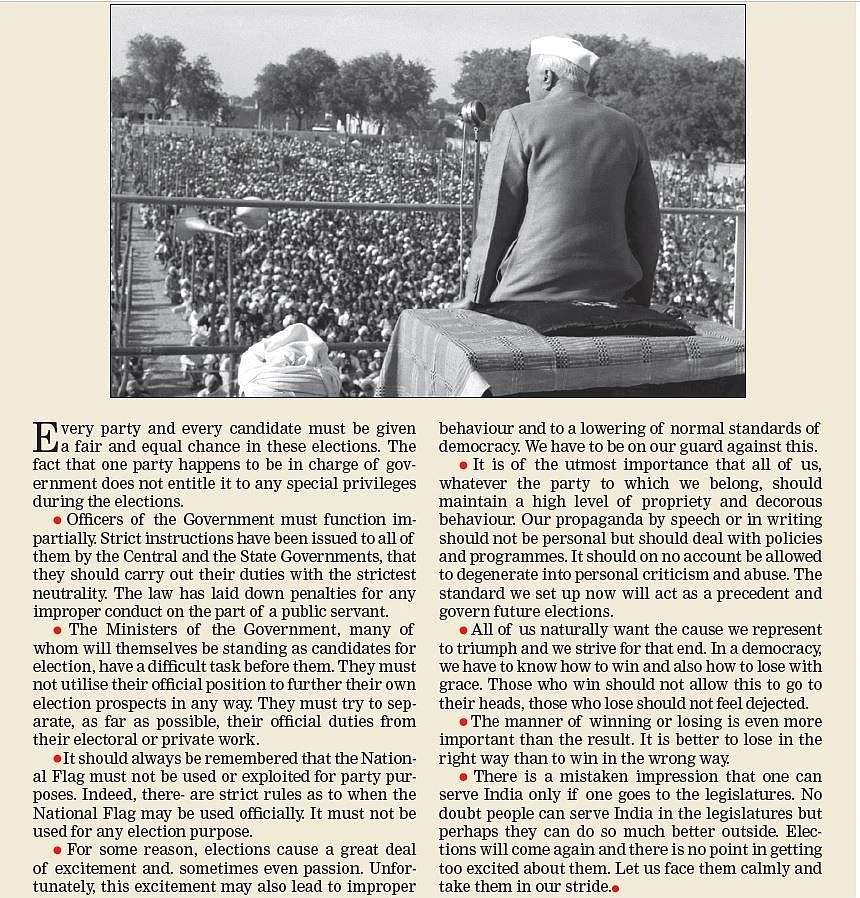

Nehru’s commitment to parliamentary democracy is shown by the seriousness with which he treated the business of elections. He did not use the excuse of Partition of the country and the consequent communal violence and influx of refugees to postpone elections.

On the contrary, he was impatient to go to the people and was not happy that the elections could not be held earlier. He converted the election campaign into a referendum on ‘the idea of India’, challenging the communal forces responsible for the Mahatma’s assassination who had been demanding a Hindu Rashtra.

It is a measure of his faith in the wisdom of the people that the communal forces were badly beaten, securing only around six per cent of the vote and 10 out of a total of 489 seats as against the Congress’s tally of 364 seats.

His primary concern as it emerges from these speeches is with the threat posed by communal parties and organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha, the RSS, Akali Dal, Ram Rajya Parishad, etc. He was very concerned that despite the country having suffered Partition due to the communal politics of the Muslim League, some people had still not understood the dangers posed by communal ideologies, and were now falling prey to their Hindu and Sikh versions.

He is also forthright in defending the Congress, while admitting to its many weaknesses, and arguing that people still had faith in it, and it had a historic role to perform. Some of his statements and that of his critics in fact have a very contemporary ring, and readers may well get a feeling of déjà vu.

Another striking feature is the lack of any animosity towards his opponents, and an effort to explain issues, including complex ones of foreign policy, Kashmir, refugees from East Bengal, etc. in a serious manner to the common man and woman.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines