Add two tablespoons of nostalgia and stir

In the latest instalment of her column 'Eat.Wander.Repeat, Denise D’Silva tries to find out what makes community cookbooks repositories of comfort and joy, even in the age of Google and YouTube

The year is 1990. You’re craving comfort food — a simple, homecooked dish that your mum used to make. But you can barely boil water. Restaurants don’t do this kind of food — it’s very particular to your community. Your neighbour, who knows everything about everything, is out of town.

As are your folks. What do you do? Before you answer, remember, Google isn’t even a word yet. You simply turn to the kitchen cupboard or the bookcase and reach for a well-thumbed cookbook. You leaf through it till you find the recipe for the dish you’ve been craving, with handwritten notes alongside.

These tweaks to the original recipe, hurriedly scribbled by your mum or your aunt, were made to suit your family’s tastes. It’s not just a family heirloom, it’s your community cookbook — wholly dedicated to the people, stories and dishes that make you unique in this multicultural country.

Community cookbooks in India are more than regular recipe books. They are volumes that preserve the distinct voice of a people and place, evoking the same kind of nostalgia in me that a sepia-toned photograph might. Especially when I see that yellow-red curry stain appropriately splattered near a recipe for ‘Sunday chicken curry’!

In an Indian Catholic home like mine, the stages of a child’s development unfold thus — soon after you learn to walk, read, write and cross your t’s, you are allowed to pick up the most prized book in the house, The Chef by Isidore Coelho.

It has some of the nicest names for recipes like ‘cockles with mutlin’ (dumplings) and ‘chou-chou’, a handmade noodle dish. It covers food from Goan, Mangalorean and East-Indian kitchens, as well as dishes beloved of the Parsis, Bohra Muslims, Anglo-Indians and Maharashtrians.

In some ways, it represents Bombay and its milieu to me. It has 1,514 recipes explained in great detail along with some interesting illustrations.

The Chef also offers tips on living right. It is filled with instructions on first aid, and food remedies for all sorts of ailments (which we nowadays pop pills for). One section is devoted to specific recipes for bachelors and children.

The author’s references to people he knew and their family recipes make it even more endearing. For instance, there is a ‘Megan’s chicken curry’. Who Megan was, and what her relationship to Mr Coelho might have been, is anybody’s guess, which only piques one’s appetite even more.

I imagine Megan as a pretty Anglo-Indian lady, who knew how to whip up a feast in a matter of minutes when guests came home unannounced. It’s this sort of thing that makes a daunting book with hundreds of pages such an inviting read.

There is a whole chapter on economising and entertaining within one’s means. Time-tested, practical wisdom distilled into a book that offers far more than its name reveals.

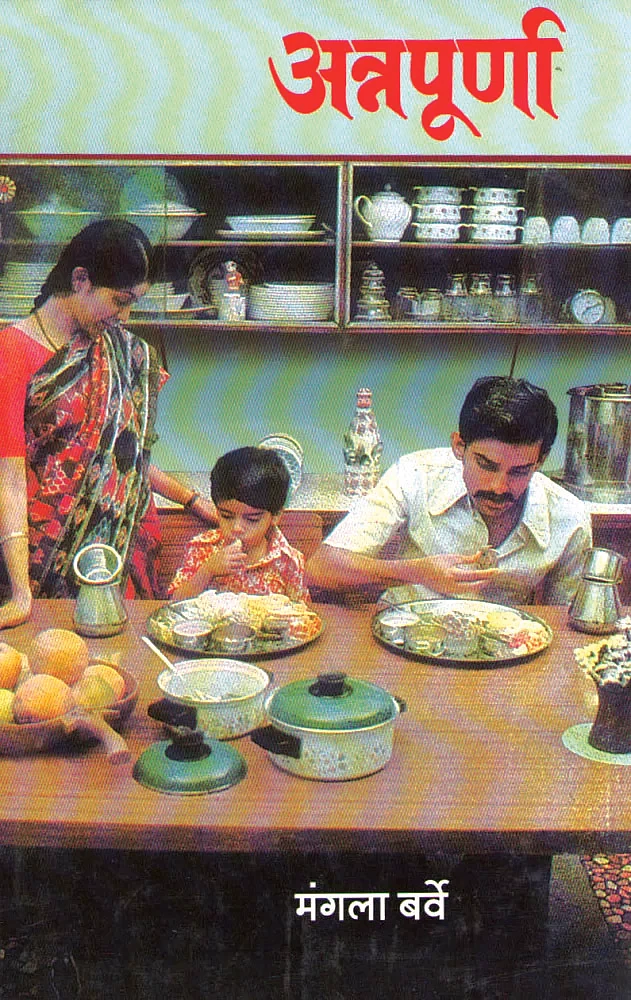

Then there’s Annapurna. A book that most Maharashtrian women pass on to the next generation. Not only does it provide the most essential recipes from within the community, it also exposes the reader to cuisines of the world (before this became a norm). So you learn how to make both Swiss rolls and palak with fresh cream, while a diagram shows you how to serve traditional fare on a banana leaf.

Being exposed to these community cookbooks put me in a strange predicament while writing about Indian food for the US market. It occurred to me that most of the measurements we follow in our kitchens and the words used by the authors of these books are very specific to India.

For instance, a vaati or katori — which is simply the Marathi/ Hindi word for a particular steel bowl placed on a serving plate — is used as a measure for lentils, grains, etc. How would I translate that into ounces? And how would I explain ‘use a lemon-sized ball of tamarind’ without totally misleading the reader, depending on which side of the world she gets her lemons from?

I remember going to my Maharashtrian friend’s place one afternoon. Her mother brought us something to drink along with faraal, a variety of crunchy Maharashtrian Diwali goodies. Diwali holidays were round the corner, and the snacks had been made at home for the festival.

They were delicious, to say the least. While we stuffed our faces and played some silly game, a neighbour came over to ask aunty if she could quickly check her copy of Annapurna to confirm whether she should use rava (semolina) or rice flour for one of the snacks she was making.

Swiftly and deftly, Aunty shoved the book out of sight under some newspapers and answered her neighbour with a friendly “Oh, rava is fine!” It was then that I realised that these books aren’t merely reference material, they are ammunition passed down from mother to daughter to ace the domestic battle. And that food neighbourliness did not necessarily mean sharing those secrets!

When I started to learn cookery, I also turned to books that showed me how others did it. Among them were Vividh Vani and the Time and Talents Club Cookbook. Ever heard of them? These are legendary within the Parsi community. Particularly Time and Talents.

First published in 1935, it has recipes that range from Parsi must-haves like akuri (spiced scrambled eggs) and prawn patia, to many international dishes like Lancashire Hot Pot and Sudanese falafels (better known as Tamiya). The thing that never fails to amuse me are the italicised quotes that appear in between the recipes.

One such is this classic from Voltaire, "The fate of the nation has often depended on the good or bad digestion of its prime minister." Or Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure being the headline for a section that helpfully converts the American system to the metric system used by us. Delightfully apt diversions from a community that relishes humour along with morsels of salli boti.

Vividh Vani is a two-volume tome written in Gujarati in 1894 by Meherbai Jamshedji Wadia. She enjoyed the privilege of an education, but still chose to spend many hours in the kitchen, honing her talents and writing down her recipes. In its pages you will find Parsi classics as well as very British creams and tarts. The challenges faced by an elegant Parsi lady while cooking on a coal or woodfired stove are also addressed.

When I need a pick-me-up (both emotional and culinary), I turn to The Best of Goan Cooking by Gilda Mendonsa. It catalogues Portuguese and Konkani influences in Goan food and treats the reader to interesting surprises. For instance, the Sorpotel song:

From the hotchpotch known as haggis, let Scotchmen yearn or yell

From the taste of Yorkshire pudding, let the English fondly dwell

From their famed tandoori chicken, let Punjabis praise like hell

But for us who hail from Goa, there’s nothing like Sorpotel!

Sorpotel Sorpotel

Every Goan loves Sorpotel!

Sorpotel Sorpotel

There’s nothing like Sorpotel!

From the bigwigs in Colaba, to the small fry in Cavel

From the Goan tribes in Bandra, to the remnants in Parel

From the lovely girls in Glaxo, to the boys in Burma Shell

There’s no Goan whose mouth won’t water, when you talk of Sorpotel!

If this doesn’t represent Goa, its society and its food in a nutshell, while encouraging you to sing along without even knowing the tune, I don’t know what will!

As a food writer, the subject of cookbooks has always been close to my heart. There is a world of riches to discover in the pages of these painstakingly written — and personally annotated — books. Even in the age of Google and YouTube.

And they always had multiple uses — as essential guides for brides navigating a new home, survival guides for single men who had come to the big city in search of work, style guides for the genteel older lady of the house still keen on impressing dinner guests.

However tattered or battered they may be, they take pride of place on bookshelves. Not only because they are repositories of rare recipes, but also because they provide commentary on a particular culture.

If you think about it, these recipe books are like archives of feelings, tastes and glimpses of a bygone era. Times may have changed and gadgets turned our kitchens into laboratories, but when we feel the need to connect with the quintessential romance of food, we can find it in the words that have been weighed and written down on these pages.

(Denise D’Silva is the author of the Beyond Curry Indian Cookbook, and co-founder of Hyphen Brands)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines