Can a manufactured civilisation unseat a century of self-respect?

What is taking place in Varanasi is not a simple cultural festival. It is a political attempt to rewrite belonging using geography and nostalgia

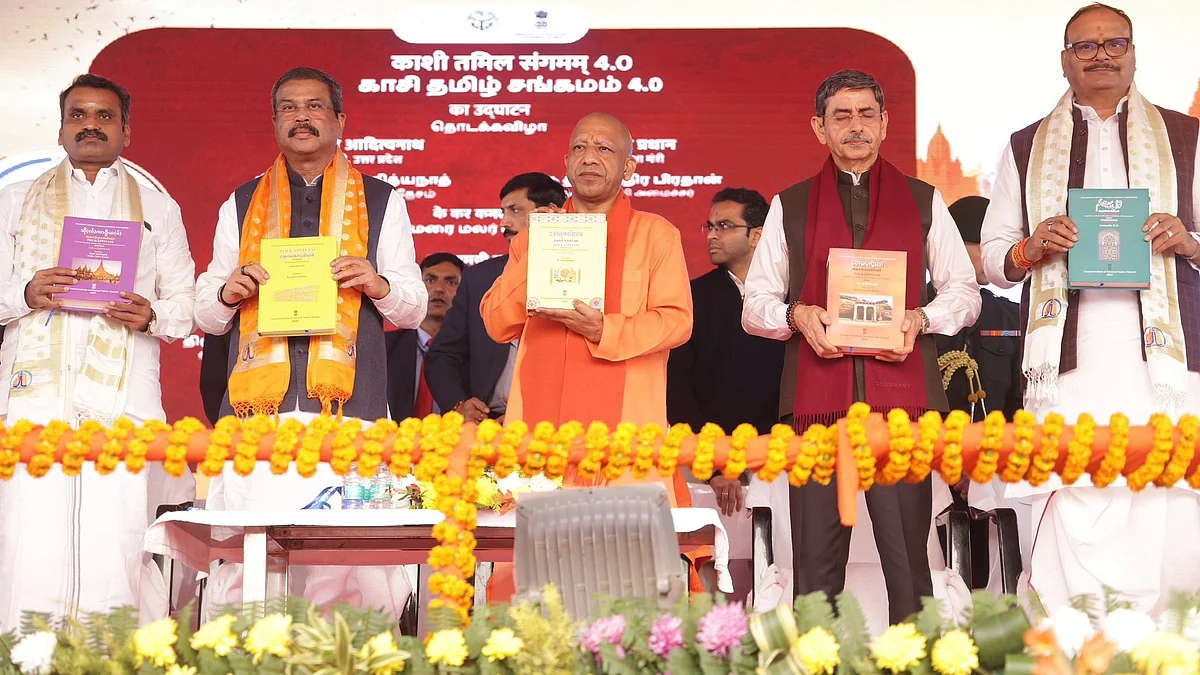

The fourth edition of the Kashi Tamil Sangamam has opened on the Varanasi riverfront with great confidence and colour. Lamps glow on ancient steps, television cameras focus on saffron banners, and young delegates from Tamil Nadu move through carefully staged cultural scenes. Union ministers speak of a shared destiny.

In his recent radio broadcast, the Prime Minister said the Sangamam is a rediscovery of civilisational kinship and called Tamil Nadu and Kashi long-lost siblings finally meeting again. Leaders in Uttar Pradesh repeat the same promise of a cultural revival that will restore what they describe as ancient unity.

From the outside, the whole event looks like a theatre trying to become a holy text. Yet something important is missing. Tamil Nadu is not reacting like a long-lost sibling at all. It is watching with quiet intelligence, like a neighbour invited to a function whose meaning is clear to someone else but not fully convincing to those who were asked to attend. For all the choreography in Varanasi, the cultural tremors stop far short of reaching Tiruchirappalli, Madurai, or Tirunelveli. Tamil soil stays calm and unimpressed.

What is taking place in Varanasi is not a simple cultural festival. It is a political attempt to rewrite belonging using geography and nostalgia. Kashi is shown as the centre of Hindu civilisation. Tamil culture is asked to circle around that centre with gratitude.

Ancient references are selected from history, neatly arranged, and displayed as proof of unbroken civilisational continuity. The message is that Tamil Nadu has forgotten where it truly belongs and must now remember it by looking towards the North.

Memory is a sensitive political tool. It can be rearranged easily. Forgetting needs only distraction. Remembering can be controlled with bright lights and serious voices. But the Kashi Tamil Sangamam faces a problem when it enters Tamil Nadu.

Memory in this state is not decorative nostalgia. It is a strong public habit that has been built through argument, protest, and reform. Tamil identity was not handed down by monuments or priests. It was shaped by debate, social demands, and leadership from common people.

It is true that Tamil Nadu and Kashi have points of contact in their histories. Some pilgrims travelled north, some monasteries had links, some royal journeys took place, and a few devotional texts spoke of the Ganga or Kashi’s shrines. Lingams were brought home, and ideas were exchanged. But these were scattered events that did not define public life. They did not create a civilisational corridor. A few journeys across a thousand years cannot redefine an entire identity.

In truth, Tamil life was rooted in its own soil and sea. Rice fields along the Cauvery set rhythms of labour and ritual. Maritime trade shaped coastal life and imagination. Jain and Buddhist influences created values of compassion known as Jeeva Karunyam.

Sangam literature described love, war, nature, and ethics in Tamil words and Tamil forms. Folk gods watched over village shrines long before monumental temples. When Bhakti poetry arrived, it did not protect hierarchy. It offered ordinary people a direct voice to the divine without a gatekeeper.

The modern age made this questioning even more open. Tamil journalism, print culture, and literary groups began speaking clearly about caste injustice and social reform. The Dravidian imagination asked for dignity in public life and social equality. Annadurai and Karunanidhi gave this imagination shape and turned it into mass politics. They used newspapers, ration shops, cinema dialogues, school reforms and public speeches to create confidence in ordinary citizens. They told people that Tamil identity is not a favour given by those who claim ritual power. It is pride in language, dignity in work, and equality in society.

Under DMK governments, this belief became policy. Reservation expanded. Midday meal schemes grew into powerful welfare models. Public libraries and affordable cinema made knowledge popular. School enrolment for girls improved. Funds reached rural local bodies. The idea of self-respect was celebrated every year.

DMK did not only speak of pride. It linked pride to a structured programme of social justice. It taught that a Tamil citizen can pray in any place of worship but must never surrender their democratic rights. Annadurai spoke against superstition and narrow control. Karunanidhi wrote poems and screenplays that questioned privilege and challenged injustice. The DMK years created a living memory that tied identity to public welfare and secular opportunity rather than ritual and submission.

This history matters today because the Sangamam tries to remove the difficult questions from Tamil memory. In the version told on the ghats of Varanasi, there is no Periyar raising his voice for rights. There is no Annadurai telling people that language belongs to them. There is no Karunanidhi shaping mass politics through writing, cinema, and clear public service. There is no Justice Party demanding equality, no women in villages insisting on education, no bus conductor reading a political magazine at night, and no theatre audience applauding a dialogue on social justice. Instead, Tamil identity is suddenly projected as an extension of a river in the North.

The Sangh Parivar uses collage, not archive. It takes one story of a Nayanmar saint, places it alongside a Sanskrit hymn, adds a tale of an ancient pilgrimage, and decorates the ghat steps with Tamil designs. It sings some Tamil devotional lines alongside a Kashi aarti. Everything looks pleasant while avoiding mention of any conflict or reform. A collage comforts the mind. An archive questions it. A collage hides pain. An archive reveals truth.

The difference is the difference between myth and history. Tamil Nadu has a rich history. Even when history is uncomfortable, it remains honest. It holds beauty and shame together. It remembers both caste violence and reform struggles. It honours victories and learns from failures. It knows that progress is not a straight line of unity but a long path of argument and awakening.

The Sangamam prefers smooth stories. They look good on screen. They create political advantage. They allow a majoritarian ideology to wear a cultural mask. Hindutva politics finds Tamil Nadu difficult because identity in this state is not controlled by a central power. It is owned by citizens. Power here must listen to memory and debate.

One can respect Kashi without bowing to it. One can admire its spiritual history without calling it the centre of all culture. Cultural respect does not mean political surrender. Students from Tamil Nadu dancing on the ghats is a lovely moment. But such moments cannot erase the lived memory of a century of self-respect politics. Photographs of temples cannot undo reservation laws, land reforms, and the long struggle against caste discrimination.

This makes the Sangamam fragile. It tries to pull Tamil identity into sentimental territory. But Tamil identity is built on practical achievements and democratic rights. A state that created noon meal schemes, educational reservations, free bus travel for women, and libraries in small towns understands that cultural symbolism without structural justice is just another disguise for power.

If there must be unity between Tamil Nadu and Kashi, let it be based on equality and truth. Let it come through honest curiosity and not through hierarchy hidden under flower garlands. Let it include questions about caste, labour, language, dignity, and public policy. Let it include the story of self-respect along with the story of devotion.

Tamil Nadu’s real gift to the Indian union is its firm belief that identity must never become a weapon of domination. That belief lives in everyday life. It lives in a mother sending her daughter to college. It lives in a Dalit student speaking confidently in Tamil in a public meeting. It lives in a fisherman demanding coastal protection policies. It lives in a woman becoming president of a panchayat in a village that once denied her entry. These are not festival images. These are democratic achievements.

If truth matters, it must be clear. The historical connection between Kashi and Tamil Nadu is real but limited. It is decorative, not foundational. Tamil civilisation does not need permission from a northern river to be proud of itself. It found identity through literature, reform movements, rational politics, and social justice. It listened to reformers more than to priests, to poets more than to royal patrons, and to movements more than to myths. That is why Tamil Nadu remains cautious today. Not angry. Simply attentive and wise.

Festivals have their place. Cultural exchanges are healthy when they invite disagreement and depth. But history needs honesty and not choreography. If a meeting of civilisations must take place, let it allow contradiction. Let Tamil speakers in Kashi mention not only ancient saints but also social rights and equality.

Until that day comes, the Kashi Tamil Sangamam remains what it is. A bright show on a river. Beautiful to see. Easy to photograph. But a mirage. Tamil Nadu’s self-respect is quiet. It stands firm and remembers. Memory becomes resistance. Resistance becomes belief. In the final analysis, this is not only about one festival. It is about the nature of belonging in a democracy. Belonging must rise from truth and not from spectacle. Tamil Nadu has chosen truth. The rest is performance.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines