Fixing the voter list or fixing the elections?

The ECI’s unwillingness to seriously engage with the Opposition’s concerns—brushing them off as politically motivated—has only deepened public distrust

The Election Commission of India’s recent invitation to Rahul Gandhi, Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha, for a discussion on his objections regarding the Maharashtra assembly elections has triggered a fresh wave of political contention.

The Congress party, pushing back against the ECI’s request, has demanded transparency through access to machine-verifiable electoral data and video footage of polling, citing widespread irregularities in voter rolls and polling figures.

The confrontation has once again spotlighted growing concerns over the ECI’s neutrality and credibility. An eight-member internal panel of the Congress, called the Empowered Action Group of Leaders and Experts (Eagle), has declined to meet with the Commission unless critical data and surveillance footage are shared beforehand.

For context, the ECI in December 2024 changed rules to deny public access to data and documents, which till then were freely available. On 18 June, it issued a circular notifying that CCTV footage at polling booths, strongrooms and counting centres would be destroyed 45 days after the declaration of results, unless election petitions challenging the results are accepted by high courts within that period. (The earlier rule was to retain polling station video footage for a year.)

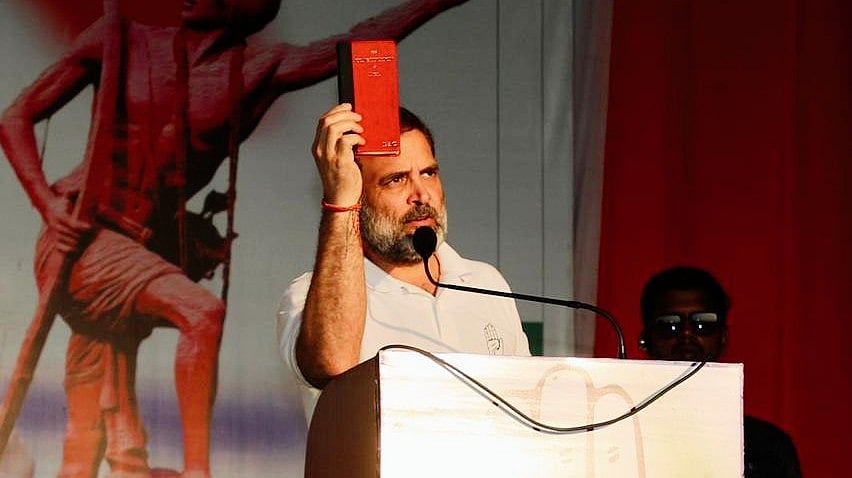

On 21 June, Rahul Gandhi reacted sharply via a post on X: ‘Voter list? Will not provide in machine-readable format. CCTV footage? Hidden by changing the law. Polling videos and photos? Now to be deleted in 45 days instead of a year. The one meant to provide answers is now deleting the evidence.’

Political analyst Yogendra Yadav added his voice to the growing criticism, saying: “Democracy thrives on openness. The ECI’s move to shorten the CCTV footage retention period—from a year to just 45 days—only deepens public suspicion and erodes trust in the electoral process.”

This sequence of events has not only intensified the confrontation between the Congress and the ECI, but also raised broader questions about institutional accountability and the shrinking space for transparency in India’s democratic machinery.

Rahul Gandhi and the Congress party have formally alleged that the 2024 Maharashtra assembly elections were marred by serious irregularities. Their principal charge involves a suspicious spike in the number of registered voters compared to the Lok Sabha elections held just six months earlier. They have drawn attention to the massive net addition of 40 lakh voters (48 lakh new names added and 8 lakh deleted) and an “inexplicable upsurge in polling after 5 p.m. on election day”. (from 58 per cent declared at 5 p.m. on polling day to 66 per cent the next day!)

In a detailed letter to the ECI, Praveen Chakravarty, Congress’s head of data analytics, highlighted the anomalies: ‘We had presented data showing an abnormal increase in the total number of new voters enrolled, and votes polled in the assembly compared to the Lok Sabha elections held just six months earlier... Forty lakh new voters were enrolled and 75 lakh additional votes cast in the Vidhan Sabha elections. This represents a 4.3 per cent rise in voter enrolment and a 13 per cent increase in votes polled—figures that are significantly out of line with historical trends in Maharashtra.”

---

Rahul Gandhi has raised the pitch of his criticism of the ECI, accusing it of facilitating “vote theft” and demanding access to a “machine-readable, digital copy of the Maharashtra voter lists and video footage from polling day” before agreeing to any dialogue.

The Congress party insists that without booth-level Form 20 data and CCTV footage, any conversation with the Commission would be meaningless. For the Opposition, verifiable electoral data is not a formality—it is the basis of electoral legitimacy.

On 26 June, West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee jumped into the fray. Addressing reporters in the coastal town of Digha in West Bengal’s Purba Medinipur district, she said: “Their [The ECI’s] target is Bengal. The migrant workers and the people of Bengal. The EC’s plan is alarming for democracy.” She was responding to questions on the ECI’s intensive revision of electoral rolls for Bihar, which goes to polls later this year. Banerjee was suggesting that the voter roll manipulations in Bihar were only a teaser preview of what was to come in Bengal, which goes to polls next year.

Rahul Gandhi has repeatedly raised an alarm over the erosion of electoral fairness, calling the 2024 Maharashtra assembly polls symptomatic of “industrial-scale rigging involving the capture of our national institutions”. Voter rolls and surveillance footage are not optional extras, but instruments of accountability, he has argued. “These are meant to strengthen democracy, not [to] be locked away while democracy is undermined.” He has accused the ECI of not merely stonewalling but “actively destroying evidence”.

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) has echoed these concerns. In a statement to The Wire, ADR co-founder Jagdeep Chhokar called the ECI’s repeated claims of transparency “hollow,” noting that the Commission’s refusal to release machine-readable data undermines its credibility. He too highlighted the surge in the number of voters in Maharashtra.

---

One of the more contentious decisions of the ECI has been the amendment of Rule 93 of the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961. In December 2024, the ECI modified this rule to significantly restrict public access to CCTV footage from polling stations.

The ECI justified the amendment on grounds of protecting voter privacy and complying with Supreme Court directives related to the secrecy of non-voters. Chhokar of the ADR points out that while privacy is important, it cannot come at the cost of transparency. “The ECI’s responsibility is to strike a balance between privacy and public accountability—not to use privacy as a shield against scrutiny,” he says.

The Maharashtra controversy, now colliding with the build-up to the Bihar elections, underscores a larger crisis of credibility confronting India’s electoral process. The ECI’s unwillingness to seriously engage with the Opposition’s concerns—brushing them off as politically motivated—has only deepened public distrust.

Congress data analyst Praveen Chakravarty summed it up succinctly: “The ECI is not a private corporation—it’s a constitutional body. It owes citizens data-backed clarity, not vague platitudes. If everything is above board, prove it with evidence.”

Democracy activist M.G. Devasahayam, a former Army officer and IAS official, was scathing: “Total secrecy has become the new trademark of the Election Commission.”

The real worry is not one state or one election. The ECI’s conduct raises fundamental questions about whether it is playing true to its mandate to safeguard India’s electoral process or shielding electoral secrets and misdemeanours or worse from public scrutiny.

---

The ‘Special Intensive Revision’ of voter rolls in Bihar has triggered a fresh wave of concern. Scheduled just months before the assembly elections due in October/ November this year, the revision exercise is to be conducted through door-to-door enumeration by booth-level officers (BLOs) between 25 June and 26 July—a period when Bihar is typically lashed by monsoon rains. Large swathes of rural Bihar become inaccessible during this time and many districts are already under orange alerts for heavy rainfall. The logistical challenges alone raise questions about the viability and sincerity of this revision process. But the content of the revision exercise raises even deeper alarm.

As per the new guidelines, all voters—new applicants and those enrolled after 2003—must submit a self-attested declaration affirming their Indian citizenship, whether by birth or naturalisation. They are also required to provide supporting documents, including proof of their birth and that of their parents. M.G. Devasahayam put it starkly: “This is essentially asking citizens to prove their citizenship again. Are we now seeing the CAA–NRC being introduced through the back door?”

What happens to those unable to furnish the required documentation? Will their names be struck off the electoral rolls? If so, it could lead to sweeping disenfranchisement, particularly in a state like Bihar where the official birth and death registration is still under 75 per cent.

Chhokar warns against shortcuts: “There’s a legal and well-defined process for removing names from the voter list. How can you bypass the process with a new declaration requirement?”

These changes, though presented as administrative steps to clean up the voter list, have raised suspicions that Bihar could see the same kind of alleged electoral irregularities that the Congress has flagged in Maharashtra.

In a recent op-ed for the Indian Express, Rahul Gandhi warns: ‘The match-fixing of Maharashtra will come to Bihar next, and then anywhere the BJP is losing.’ RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav has echoed the sentiment: “The BJP has been exposed… The whole world saw how the Maharashtra elections

were won.”

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines