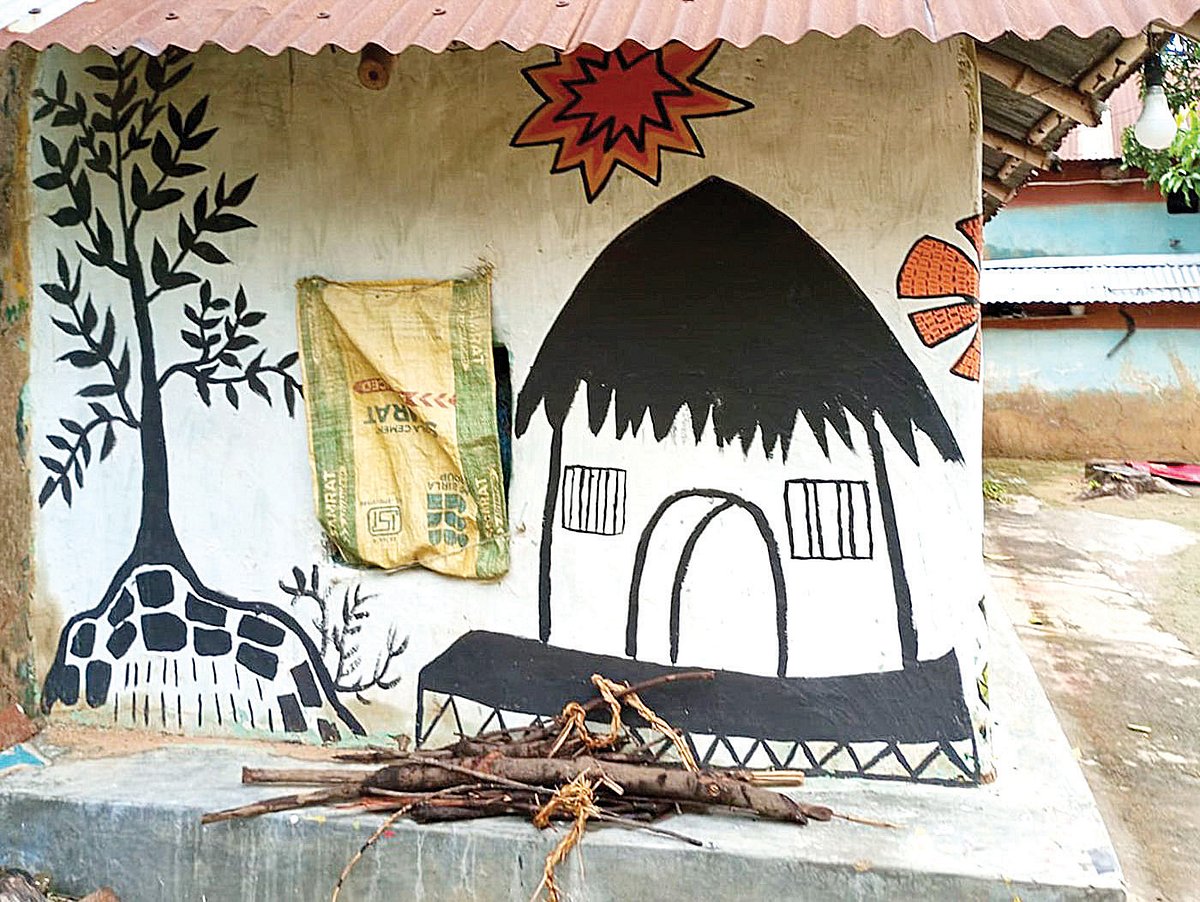

In Birbhum, forests bloom on Santal walls

A walk in a colourful Santal village in Birbhum reveals the close connection this tribal community once had with their forest

On the mud walls of a small Santal house in Gopalnagar, trees rise through the roof to merge with the umbrella of the neem tree growing beside it. The path on which a male spotted deer and its fawn amble along is lined with tiny flowers and giant butterflies. Bright colours fill the decorated wings of larger than-life versions of bulbuls, babblers, barbets and parakeets. These avian inhabitants of the nearby Illambazar forest flutter against the dull white of the wall.

The pitch road that cuts across this village in Ilambazar block is dotted with many such Santal mud huts on either side. It’s not the music of unseasonal showers on her tin roof that alerts 75-year-old Churki Tudu. Rather it’s the sound of our footsteps as we walk along this painting, spread like kantha-in-clay on the outer wall of the house.

“Kids these days do new designs from phones and newspapers. Where was such variety in our times? We’d simply get some mud from the field and splash colours on the walls,” says Churki Tudu as she steps out of her room and stands at the entrance of her house. The ease with which she speaks tells us that she is used to curious visitors stopping to photograph the decorated walls of her house.

She doesn’t wait for us to ask, but rather dives straight into the subject she assumes we are interested in. “White mud, red mud, black mud (colours) made with hnarir tel (burnt oil residue scraped from cooking vessels)—these were the colours.” A pause, and she continues. “First, the old layer of clay would be scraped off the wall. Then a fresh layer of mud would be plastered and we would apply another coat. Finally, we would colour the border with kharimati (limestone or chalk).”

Churki is nostalgic about her childhood days in her birth home at Purba Barddhaman’s Akulia village. But she is aware of the Santal community’s rapidly changing ways, and the manner in which the new generation is adapting. She currently lives with her daughter in Gopalnagar. Their home is one of the 304 households in this village situated to the left of the Sriniketan Road, on the way to Ilambazar forest from Bolpur.

Roughly seven per cent of the total population of Birbhum are Adivasis. Santals are the majority—over 80 per cent (Census 2011).

“Most families in the village have two homes: a mud house and a cement one. The wall art is made on the mud house,” says Sumi, Churki’s 40-year-old daughter.

As she explains the practice and the tradition, we suddenly notice that everyone here has built a pucca house of brick and cement, right next to their traditional houses. Much like a modern extension. For them the acceptance of the new doesn’t seem to have come at the price of the old.

The mud for the walls comes from the fresh layer of silt that gathers on the ground during the monsoon. “We collect the silt from fields in the months of Bhadra and Ashwin (mid-August to mid October),” says Sumi. For the annual Santal ritual of painting the house, the colours were traditionally sourced from various types of mud.

“Adivasis have four primary colours,” says Gagani Mandi, 40, Sumi’s friend and next-door neighbour. She goes to list them: “Kharimaati (chalk) is used for white; Laalmaati (red mud) brought from Ilambazar forest is soaked in water. Typically, we make borders with it. Sometimes we find yellow mud while boring a well. We don’t get much of that. So, whenever we do, we preserve it carefully in sacks to be used later for painting. Then there’s black. We burn straw and mix the ash with water to get that colour.”

Gagani goes on, “Sometimes we mix kharimaati with readily available blue to create new colours for painting. We also extract green from the leaves of shim (snow peas),” says Gagani. “These (natural) colours often fade over time and so we need to apply them again (annually).”

And what about all the other colours used in the mural depicting birds, flowers and animals on the wall of that house we saw first? “The rest of the colours are all bought from the market,” says Gagani.

“See those two houses with butterfly designs? All painted by Purnima. We just help her,” says Sumi’s daughter Rekha Murmu. The 16-year-old proudly introduces us to the busy artist working intently on a wall a little further in the village. Both she and her young painter friend Purnima Murmu, 15, study in Class 11 in Raipur Sitikantha M. High School and Daranda Chandimata Vidyalaya respectively.

Rekha, a native Santali speaker, is also fluent in Bangla, like everyone in Gopalnagar.

All those birds, butterflies and human figures on the walls of Rekha’s own house are not their traditional motifs, nor are their methods. “We have learnt all these from a didi (elder sister, as teachers are addressed) who comes to teach us painting,” says Rekha, making it clear that the teacher is not from the Santal community. The paint, brush and palette that Purnima is using are all bought from the local market in Bolpur.

“Earlier, we did not paint the entire wall. There would be a red clay borderpainted right under the straw thatch, with flowers and vines painted under that. It was simpler,” says Rekha. Like her grandmother Churki, she understands that the figures and designs in the older paintings were part of a way of life that doesn’t exist anymore.

Churki Tudu cannot remember the last time she saw a child paint a bow and arrow. She says that people don’t paint those things nowadays; hunting is now banned. What they practice once in a year on the day of Bandna Parab (celebrated by Birbhum’s Santal community in the first week of January) is more of a performative ritual, a symbol that traces back to their status as hunter-gatherers prior to being cultivators. Birbhum is also fast losing its forest cover.

“Most Santal families in Gopalnagar are sharecroppers working on others’ fields. We grow paddy in the monsoon and potatoes in winter and depend on this harvest for our yearly grain for meals,” says Gagani, sitting on the floor inside the pucca part of the house scattered with harvested potatoes.

The division of the harvest is decided between the landowner and the sharecropper on the basis of who invests most in seeds and fertilisers. Only a handful of families have land of their own. That too one or two bighas at the most. (A bigha here is 0.33 acre.) Besides paddy and potatoes, they cultivate mustard, sesame, brinjal and tomato.

Rearing livestock, running tea and snack stalls and battery-operated e-rickshaws are additional means to earn. But life still revolves round the harvests. “We usually paint our walls during Aghran (mid-November to mid-December) before the Bandna festivities,” says Sumi. Applying a fresh coat of mud on the walls every year and maintaining it is largely done by the women in a Santal family.

Why decorate the houses now, when it’s not festival time? It’s also done during family weddings, Rekha explains. They are expecting one soon in Purnima’s house and so, the women in the family are decorating the walls. The resident artists have moved the furniture around. The portraits of Raghunath Murmu (renowned Santali scholar, playwright and creator of the Ol Chiki script), Dr B.R. Ambedkar and Rabindranath Tagore have been taken off the wall and are resting on a bed. Rekha says that the three portraits housed here are community assets, in demand for display during festivals and celebrations.

What binds the Santal women of Gopalnagar village through generations is the distinctive tattoo that they—Gagani, Sumi and Rekha’s friend Brishti— wear on their upper chest. “It hurts a lot. So I got mine on my hand,” Rekha says enthusiastically, stretching out her arm adorned with flower-patterned tattoos similar to the one her mother has on her chest. From Sumi to Rekha, this marks a rite of passage.

“We all have to get these tattoos done when we are 5 or 6 years old. People from Bihar come here to get them done. It hurts more if we wait till we are grown up. This is our symbol. Ma-Dadi (mothers and grandmothers) have passed these on to us. The colour fades slowly (with time),” Sumi says with a smile.

Courtesy: People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines