Why Aurangzeb lies buried under the open sky

In his last days, Aurangzeb was seemingly full of contrition for past deeds, and wished his burial to be as modest as possible

The grave of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, remembered in popular accounts as an intolerant despot and tyrant, has become the latest high-profile target of the ongoing villainisation of Muslims in India. On 17 March, coinciding with the day in the Hindu calendar when Maharashtra celebrates Shivaji Jayanti, Nagpur was engulfed in communal violence over demands to remove the grave — an ultimatum that found the open endorsement of chief minister Devendra Fadnavis.

Watching all this unfold with a strangely mottled sense of inevitability and disbelief, I was reminded of my visit to Khuldabad, where Aurangzeb’s grave lies. Khuldabad is located in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (formerly Aurangabad). When I visited Aurangabad around five years ago, in 2019, my primary interest was in Ajanta and Ellora. After spending a day there, I decided to visit Khuldabad, which is just 3 km from the Ellora caves. Given that Khuldabad houses the grave of an emperor, one might expect a touristic buzz here. But the place felt like a sleepy village.

The grave complex also houses a shrine to Aurangzeb’s spiritual guide Sheikh Zainuddin Shirazi. While the shrine drew my attention, I couldn’t at first see Aurangzeb’s grave. I had to ask a local where it was, and he led me to the southeastern corner, unlocked a gate and pointed to the grave.

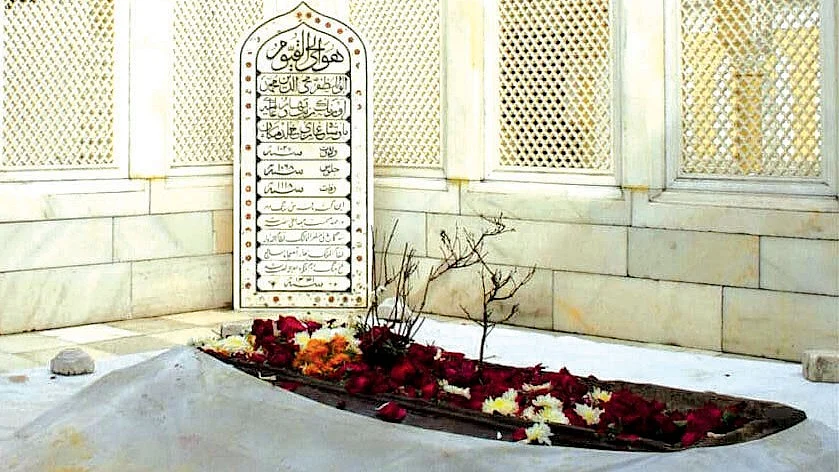

If memory serves me right, his name was Mohammed Insar Ahmed. The grave remains locked and is opened only when there is a visitor, he explained. I was taken aback and asked: “Is this really Aurangzeb’s grave?” He pointed to an inscription in one corner of the square space, which bore Aurangzeb’s name. The inscription, in Arabic, states: “The only eternal being is Allah; everyone else must perish.”

Aurangzeb’s grave is a simple stone slab with soil on top, where a plant grows. Insar called it sabza (in effect, any handy green shoot); the plant is replaced every year. I asked why the grave was so modest — and learnt from him that Aurangzeb had explicitly instructed in his will that his grave should be built this way. The will also specified the design and location of his burial site.

I persisted: “Why did Aurangzeb wish to be buried under the open sky, without a grand mausoleum?” In his last days, Insar Ahmed explained, Aurangzeb was full of contrition for his past deeds, and he wished for his burial to be as modest as possible. His will stated that no one should mourn his death, no ceremonies held, and his grave built in a place where he would have no shade.

He expressed the wish that his face not be covered after death so he might face Allah directly. The grave, Insar explained, is an act of penance under the open sky. It is said that only 14 rupees and 12 annas were spent on Aurangzeb’s grave, and even that money came from his personal earnings. He made this money sewing caps, while the earnings from writing copies of the Quran — amounting to 350 rupees — were distributed among the poor. The same complex also houses the graves of his son Azam Shah and Azam’s wife.

How accurate Insar Ahmed’s explanations were, I cannot say. But the irony is striking: the story of Aurangzeb, who chose obscurity in death, is now being brought back to life through this controversy.

Another surprising aspect of my visit was a small donation box in one corner of the grave site. Insar gestured I might like to make a contribution.

When I asked what the money was for — whether it was used for the upkeep of the grave — he candidly admitted, “No, we keep it for ourselves.”

Aurangzeb’s grave is a nationally protected heritage site. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) funds its maintenance; the waqf board also participates in its upkeep. Recently, the Hindu Janjagruti Samiti claimed that Rs 6.5 lakh was allocated for its maintenance over three years during Narendra Modi’s tenure as prime minister.

Khuldabad has a rich history, with nearly 1,500 Sufi saints buried here. It was once known as a rauza (garden). Besides Aurangzeb’s tomb and the shrine to his spiritual guide, the complex also houses relics associated with Prophet Muhammad, including his robe and hair.

These are displayed to pilgrims on Eid Milad-un-Nabi. A few kilometres from Aurangzeb’s grave lies the Bibi Ka Maqbara, built in memory of Aurangzeb’s first wife and Azam Shah’s mother, Rabia Daurani. The structure resembles the Taj Mahal and is often referred to as the 'poor man’s Taj Mahal'. Unlike Aurangzeb’s grave, which has free access, Bibi Ka Maqbara requires a Rs 25 ticket. Rabia’s mortal remains are kept in a basement chamber. Few people visit the site, and the maintenance is poor.

Khuldabad is also home to the revered Bhadrakali Maruti temple, which features a reclining Hanuman idol, as well as the famous Jagrut Ganpati and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj temples. Additionally, in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar’s Himayat Bagh, there is a free-entry museum dedicated to Shivaji Maharaj.

On 17 March, while inaugurating a grand temple to Shivaji Maharaj in the Maradepada area of Bhiwandi taluka, Thane district, Fadnavis declared, “I want to send a message from here — this country will celebrate only the glory of Shivaji Maharaj’s temples, not Aurangzeb’s grave.” He did concede, though, that “Aurangzeb’s grave is protected by the ASI... so its preservation is the responsibility of both the state and Central governments. Removing it involves legal hurdles...”

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines