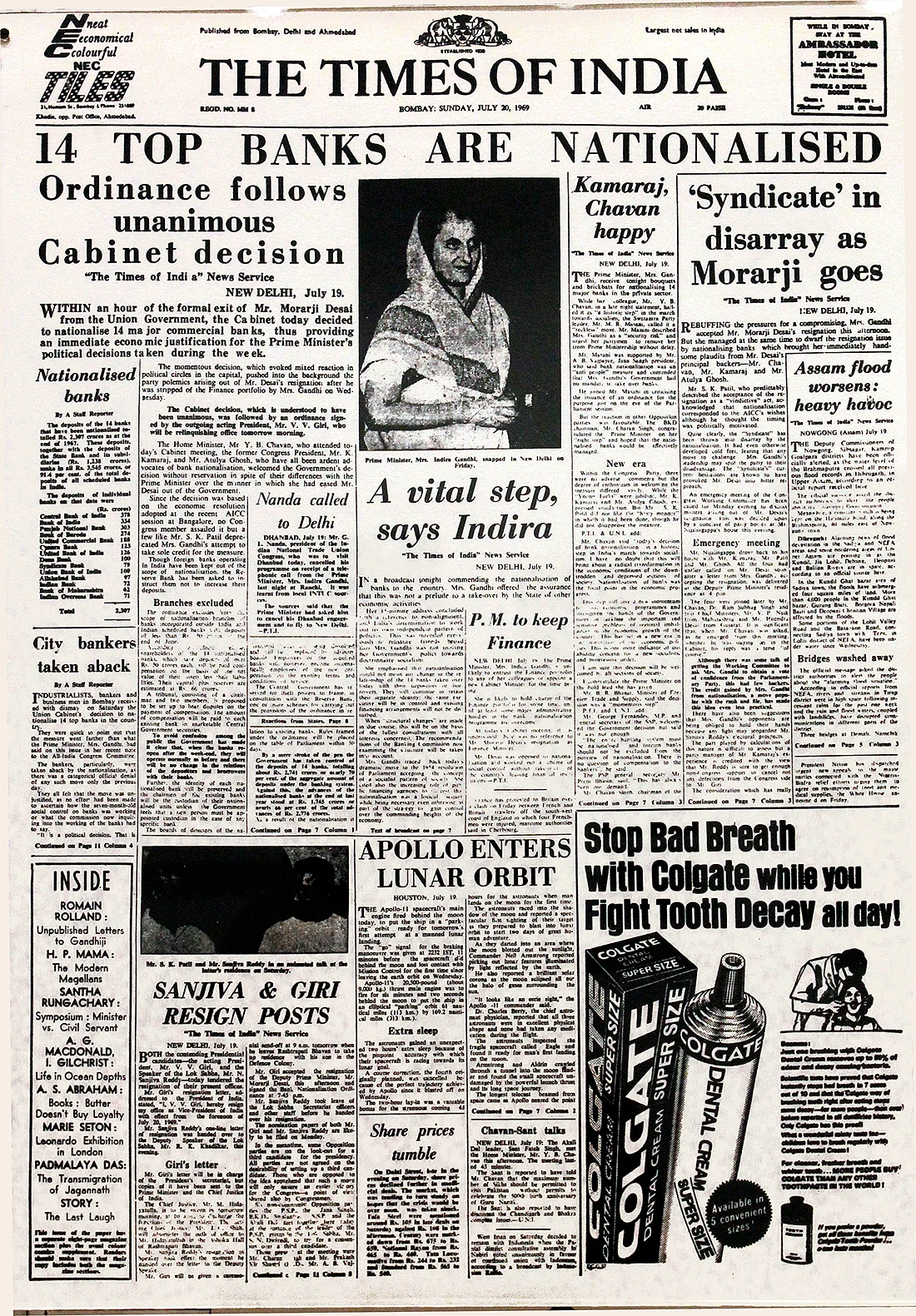

Indira at 100: 18/07/69—Indian banks nationalised, and the moon

In this extract from his memoir ‘No Regrets’, then Deputy Secretary, Banking in the Finance Ministry DN Ghosh recalls how Indira Gandhi nationalised banks almost overnight in 1969

Baksi, Haksar and I were in a huddle till the wee hours of July 18, at the end of which Haksar seemed to be broadly convinced that the proposal to nationalise banks was feasible. What was worrying him was the time factor. Vice President VV Giri was acting as the President from May 3, 1969, following the demise of President Zakir Husain; but as he was to file his papers as an independent candidate for Presidentship, he had decided to resign on July 20, which was just two days away. Could we see through the whole exercise in such a short time? Haksar did not seem inclined to express a view, however, when we were ready to leave.

‘You must see me at the South Block office at around 8.30 in the morning [18 July],’ he told me as I got ready to go home, ‘I will meet the PM at her residence at 7.30.’

I was at Haksar’s office at exactly 8.30 am, but before that, I had dropped in at my office in North Block to collect the latest statement from the Reserve Bank of India. In my capacity as the deputy secretary in the Banking Division, I used to receive a fortnightly statement from the Reserve Bank, showing deposits of major banks, that is, those with deposits of more than Rs 50 crore. This classification of banks as major and minor had a special significance in the central bank’s parlance. Banks with deposits of less than Rs 50 crore could pay their depositors a rate of interest two percentage points more than what the Reserve Bank allowed the major banks to pay.

The latest statement showed the deposits on the last Friday of June 1969. I arrived at Haksar’s office with that statement. The Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) is in the South Block, which is one of the two secretariat buildings that flank Rashtrapati Bhawan, the President of India’s official residence on Raisina Hill. The Ministry of Finance, including the Banking Division, is in North Block and right across the road. As I strolled across Rajpath on that July Morning with wispy monsoon clouds hanging from the horizon like lumps of cotton wool, what was I thinking?

The towering sandstone structures of the secretariat buildings, with their Mughal domes and the criss-cross Rajputana jaalis where pigeons build their nests, had never ceased to fascinate me ever since I first stood before them as a young member of the Students’ Federation of India (SFI) in 1947. The wonder of being ensconced within the imperial portals of North Block did overwhelm me often when I first entered the Ministry of Finance as a young official in January 1958. On the morning of July 18 though, I don’t think I was distracted at all by reveries. I was simply driven by the urgency of the moment.

The only stray thought that did impinge on my mind that day was probably the orbit of the American spaceship Columbia, around the moon. The first manned mission to the moon in human history began on 16 July, as Apollo 11 took off from the National Aeronautics & Space Administration’s (NASA’s) base at Florida in the United States. On 18 July, Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin were to separate from the command module Columbia, which would continue to orbit the moon with Michael Collins aboard, and descend towards the surface of the moon in the lunar module Eagle.

When I reached Haksar’s office in South Block, he told me that he had received a nod from the Prime Minister. I sensed the thrill of the moment. The banking industry in India was at the crossroads and only three humans knew of it at that moment—the Prime Minister of course, Haksar and I! I was shaken out of my reverie by the voice of cold reason.

‘Before I send you back to office to commandeer you again, officially,’ Haksar said, ‘can we settle a few details?’

We pored over the Reserve Bank’s statement that I had brought with me. I explained to him that the deposits of the 15 major banks, including the National & Grindlays Bank, would make up nearly 85 per cent of the total commercial bank deposits in the country.

‘Do you think so,’ he said, ‘Let us leave it out.’

Not counting the National & Grindlays Bank, the major banks in India tallied 14. Haksar asked me if I could include Andhra Bank.

‘Raghunatha Reddy is insisting that we nationalise Andhra Bank,’ he said, adding, by way of an explanation, ‘he hails from Andhra Pradesh, and he thinks that the nationalisation of a bank with headquarters in that state would be a feather in his cap.’

‘Only 14 banks. The foreign bank has to be left out.’

Andhra Bank figured just below the list of major banks with a deposit base of Rs 42 crore. I explained to him that since we were not nationalising all banks, we had to adopt some classification and the only reasonable criterion I could think of was the conventional classification that Reserve Bank had been following between major and minor banks. Clearly, if we were to follow that classification, we would not be able to justify nationalising Andhra Bank.

He seemed to agree with the argument, but said, ‘Let us see what the legal pundits have to say about it. I have asked the Attorney General to join us shortly.’

Haksar felt he should consult the Prime Minister at this stage. It was 9 in the morning by then and the Prime Minister was in her office. With the statement containing the list of major banks, minus National & Grindlays Bank, Haksar walked into the Prime Minister’s room and returned in a matter of minutes.

‘Yes! Only 14 banks. The foreign bank has to be left out,’ he said. A million words could not have held the import of that sentence at the moment. The Prime Minister had approved the proposal, but had expressed a desire to meet the ‘gentleman’ who would be entrusted with the job. My father had passed away on 24 May 1969, and in the tradition of Hindus, I had shaved my head during the funeral service. My hair had grown back somewhat, but it was still cropped close to the skull. When I stepped inside Indira Gandhi’s office, she asked me if there had been a bereavement.

When I told her that I had lost my father, she said, ‘I am sorry to hear that.’ Then she peered at me rather intently and said, ‘I have seen you somewhere before.’ She had indeed, for I had met her, if only for a brief while, in Parliament House some months before. When I said so, she said, ‘Just remind me, if you could, what it was about.’

He mentioned the sighting of a ‘Tibetan-looking’ apparition that had wound its way into the Prime Minister’s office around nine o’clock on the morning of July 18 and stayed there for a while.

On that occasion a question had cropped up in Parliament on the discriminatory treatment of Indian banks in Sri Lanka. I had sent some background material to the Ministry of External Affairs for them to prepare a draft reply to the question. A draft reply had been proposed by the External Affairs officials for the Prime Minister’s response to the Parliament question, but she was uncomfortable with the draft.

Preparing for Parliament

Indira Gandhi wanted to have a word with the officer from the Finance ministry who had sent the background material. When I received the message from her Private Secretary, NK Seshan, I had barely settled down in my office in North Block. The sprawling circular monument that is the Parliament of India sits to the east of the secretariat buildings on Raisina Hill. The Parliament House is a brisk 15 minutes’ walk through the lawns around Rajpath or a mere minutes’ drive from North Block.

A short cut exists though, through the corridors of the North Block. It leads straight up to the Parliament House. So, I was able to rush there in a matter of minutes. She showed me the file and asked, ‘is it alright? Are you happy with the answer?’

I looked at the pencil markings and my body language must have suggested that I was unhappy with the draft that the External Affairs ministry had prepared, even if it was on the basis of the memo sent by me.

‘You are DN Ghosh—you had sent the memo? So, how would you like the draft to be amended?’ she asked, handing over a pencil to me.

I made some alterations to the draft.

I had by then got up from my seat, but the Prime Minister noticed that I had barely had time to drink the tea offered to me. ‘Please, finish your tea,’ she said. ‘Be absolutely relaxed.’

‘It is alright now?’ she asked when I had finished. Then she gave it an approving glance. It was a little before Question Hour was scheduled to begin in the Lok Sabha. She called someone and asked him to tell the Speaker that the answer already circulated had to be replaced.

When I reminded her of this rather trivial incident, somehow our interactions became easier.

A rather long meeting with the Prime Minister ensued. She asked me briefly about my background. My long stint in the Banking Division handling several legislative proposals must have given her some measure of comfort. I told her specifically that I had handled several pieces of banking legislation in the past—perhaps a dozen or more—and was familiar with legislative nittty-gritty. She asked me if I anticipated any difficulty in preparing the legislative draft in a day. I think I sounded confident and she asked me what made me feel so confident.

Perhaps, she needed to be sure that this young man was not trying to impress her with mere bravado. I told her that a proposal to nationalise the top five banks had been prepared by the Banking Division towards the end of 1963 at the behest of TT Krishnamachary during his second stint as cabinet minister for economic and defence coordination. That draft had been handed over to me by my predecessor. I told the Prime Minister that tailoring that draft to fit a new ordinance would not require major changes.

‘Okay,’ she said, but as I rose to go, she added, ‘you have to do it all in absolute confidence. If there is any hitch, you should not hesitate to apprise Mr Haksar. If you have any difficulty in contacting him, you must feel free to get in touch with Seshan, so you may be able to contact me.’

I had by then got up from my seat, but the Prime Minister noticed that I had barely had time to drink the tea offered to me.

‘Please, finish your tea,’ she said. ‘Be absolutely relaxed.’

As I was gulping down the tea, my eyes lowered, I sensed she was looking intently at me.

When I had reached the door, she called out to remind me that the Vice President was demitting office on July 20.

‘So, the ordinance,’ she said, ‘has to be signed tomorrow.’

This meeting, like my midnight tryst with Haksar, was intended to be off the official records.

‘All the incidents since last evening have vanished from history,’ Haksar told me as he sent me back to my office that morning.

Press tries to solve the riddle

Years later, Baksi told me how a member of the Press had quizzed him about the events of that morning. The New Delhi correspondent of a major news agency, one AN Prabhu, had told Baksi, ‘we have been able to put together all the pieces of the puzzle leading up to the promulgation of the ordinance, but there is one little riddle we still have not been able to solve.’

He mentioned the sighting of a ‘Tibetan-looking’ apparition that had wound its way into the Prime Minister’s office around nine o’clock on the morning of July 18 and stayed there for a while. ‘We still don’t know who this Tibetan-looking person was and what he had gone there for’, the inquisitive news hound had mused. It is pertinent to mention here that the deputy secretary who did visit the prime minister’s office that morning was slightly built, light-skinned as is common among hill people in India and had hair cropped close to the skull like a Tibetan lama! Baksi told me afterwards that he simply could not stop laughing when he heard the description.

The Attorney General gave me a patient hearing. He seemed to accept the argument that the decision to nationalise banks would serve a public purpose. He also seemed to accept the rational criterion for choosing the 14 banks. After being fully briefed, he went to see the Prime Minister.

Haksar told me that I would now be ‘commandeered officially’. I returned to my office and around 10 o’clock the telephone began to ring. The Additional Secretary in the banking Division, SS Shiralkar, was on the line. I had done the entire social control exercise with him and our relations were exceedingly cordial.

‘Ghosh,’ he said, ‘I have to throw you to the wolves.’

‘What is it, sir?’ I asked. ‘Am I getting transferred?’

‘No,’ he said, ‘it’s worse, you have to go to the PM’s office.’

‘What is it about?’ I asked innocently.

Shiralkar explained that PN Haksar, Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister, needed help in replying to some Parliament questions and had asked for the Joint Secretary in the Banking Division. When told that there was no Joint Secretary in the division, he apparently asked for a director. Shiralkar had to tell him that the department did not have a director either, but there was a deputy secretary in charge of the Banking Division.

‘Does he know anything?’ Haksar had apparently asked him and my benevolent superior had assured him that I had been handling banking issues for a while.

Taken into custody

Haksar then said, ‘Can you send that chap to me. I need some clarifications.’

So Shiralkar had no option really, but to ‘throw me to the wolves’! When I reached Haksar’s office, he said, ‘Sit down, you are now officially in my custody.’

I asked him when he would call the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. He said, ‘First I need to be assured of the legalities, then I will take the Economic Affairs secretary and Governor of the Reserve Bank into confidence.’

While we spoke, the Attorney General of India, Niren De, strolled in. This tall, dark gentleman with an overbearing personality had been hand-picked by Indira Gandhi soon after she assumed office in March 1967. He had acquired a high professional reputation in Calcutta as an advocate in many difficult labour cases and was generally known to have leftist leanings.

Haksar briefed him on the decision to nationalise the major banks and sought his advice on whether the tentative list of 14 banks could be enlarged to include the Andhra Bank as well. At this point he asked me to explain my apprehensions and why I felt that including Andhra Bank in the list could be challenged from a legal perspective.

The Attorney General gave me a patient hearing. He seemed to accept the argument that the decision to nationalise banks would serve a public purpose. He also seemed to accept the rational criterion for choosing the 14 banks. After being fully briefed, he went to see the Prime Minister. While De was with the Prime Minister, Haksar got in touch with IG and LK Jha (who was then in Bombay), and asked them to come to the Prime Minister’s secretariat for a meeting early afternoon.

DN Ghosh is a former top bureaucrat, banker and corporate leader

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

- Indira Gandhi

- bank nationalisation

- Rashtrapati Bhawan

- VV Giri

- Andhra Bank

- Apollo 11

- Attorney General

- Columbia

- DN Ghosh

- Economic Affairs secretary

- External Affairs ministry

- LK Jha

- moon

- NASA

- National & Grindlays Bank

- Niren De

- NK Seshan

- North Block

- Parliament

- PMO

- PN Haksar

- Prime Minister’s Office

- Question Hour

- Raisina Hill

- Rajpath

- Reserve Bank of India

- South Block

- Speaker

- SS Shiralkar

- TT Krishnamachary

- Zakir Husain