School for Mushars: Scripting change via education

Soshit Samadhan Kendra in Bihar selects students from Mushar hamlets so that they act as agents of change by spreading awareness about the social and economic empowerment that education brings

“I want to become an engineer,” says Ram Lakhan, a Class III student. So does Class X student Mantosh while his classmate Chandan wants to take up the civil services exam to become either an IAS or IPS officer. However, Manish from Class VII is clear on what he wants to become — an IPS officer.

Perhaps, at first look, it may seem as if these children’s dreams are not much different from children in any regular school. But it is. These children hail from the Mushar community — considered one of the most backward communities and so deeply poverty-stricken that they are traditionally known to hunt rats to stem the pangs of hunger. Certainly, for children from this community, to go to school and to aspire like Ram Lakhan or Manish is no small thing.

In fact, they are slowly breaking the shackles of poverty and deprivation that have chained the Mushars for untold generations — and are stepping on to the path of achieving a pride of place in society.

The Harbinger of Change

All this is happening just about five km from the Danapur railway station, a satellite town of Bihar’s capital Patna. And, they dream because of the efforts of one person—JK Sinha, a retired IPS officer.

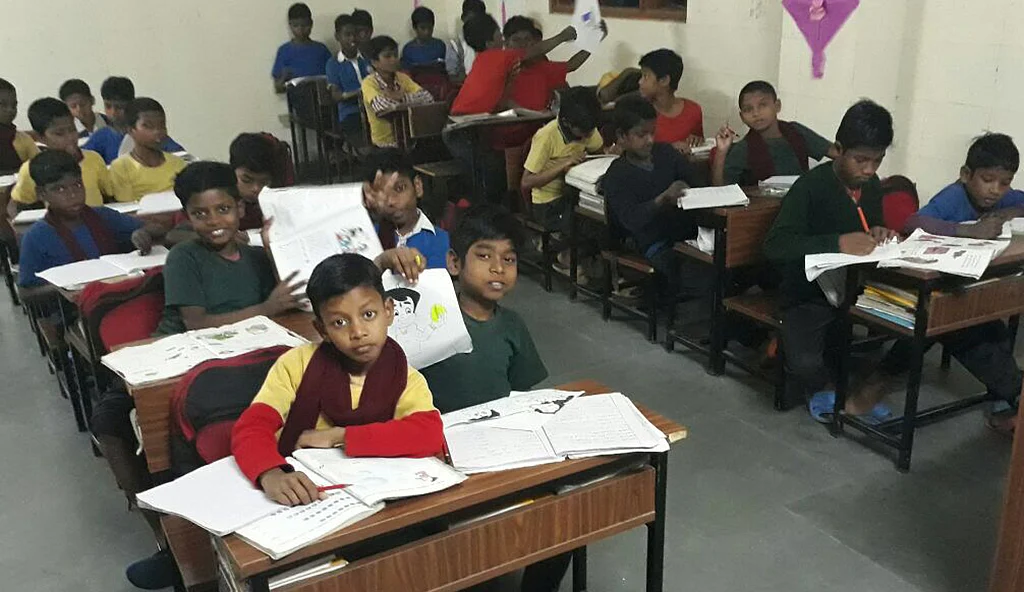

These four children are among the 435 students studying at Soshit Samadhan Kendra, a fully-free, residential, English-medium school started by Sinha, whose grandfather was the first Indian to become the police chief of a state.

Sinha began modestly in 2007 to catalyse this into a ₹20-crore school on a two-acre plot with donations, big and small. The seed money was though provided by his family and him, with the balance funds being raised over time from friends, well-wishers and corporates. He hasn’t got any government grant.

The school which is affiliated to the Central Board of Secondary Education has classes from UKG to Class XII for humanities and science streams. They currently admit 40-45 students every year at the UKG level to comprehensively mould the mindset of students.

“We had a modest beginning in 2007, and the four students who passed out of the first batch are pursuing higher education in institutions of repute,” says Sinha. Shaan Kumar and Suraj Kumar are pursuing BA LLB and BA BEd courses, respectively, at the Central University of South Bihar at Gaya; Sharmesh Kumar is a student of BBE (Bachelor in Business and Economics) at St Xavier’s College, Patna; and, Bablu Kumar is studying political science (honours) at AN College, Patna.

“We receive all the support required to even pursue college education,” says Bablu.

The Working Model

Explaining the working model of the school, Sinha says, “We select students from Mushar hamlets from different parts of the state. A maximum of two are chosen from a village, so that they act as agents of change in a wide area by spreading awareness about the social and economic empowerment that education brings.”

“Mushar population in Bihar is estimated to be between 35 and 40 lakh, of which more than 90% are landless agricultural labourers. They mostly live in abysmal poverty, well below the poverty line in designated ghettoes on the outskirts of villages. They have seen the least change in their condition – their income hasn’t risen as much as that of the other communities. Literacy among them is the lowest – approximately 3%,” says Sinha , explaining why he chose to work for them.

Noted sociologist DM Diwakar concurs. “This practice of eating rats still continues, mainly in paddy-growing areas where Mushar labourers dig earth to catch the rodents and retrieve grains, though there is no denying that food habits have changed among the community over time,” says Diwakar.

Sinha points out that it is not just a school. “We act as parents, teachers and doctor of these students, all rolled into one,” he adds. The school aims at raising its current capacity of 600 students to 1,000 by 2020.

About 20 teachers and 25 support staff work in the school and the estimated operational expenditure for 2016-17 was ₹1.84 crore. A single-storey residential school building has been constructed for now, with a foundation that will support a three-storey building.

The school’s Principal, RU Khan, says, “We provide best of education and other facilities. Even after students pass out, we provide them support till they get suitable jobs.”

He adds that there have been students who dropped out, “but that has been mainly because of the early marriage of students or early death of their fathers.”

A great beginning has been made, nevertheless.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines