Has India ended up ceding land to China as part of the ‘disengagement’ in Ladakh?

The larger question remains as to the objective behind China’s push into Eastern Ladakh, especially when it had invested heavily in men and material to secure and control the areas they overran

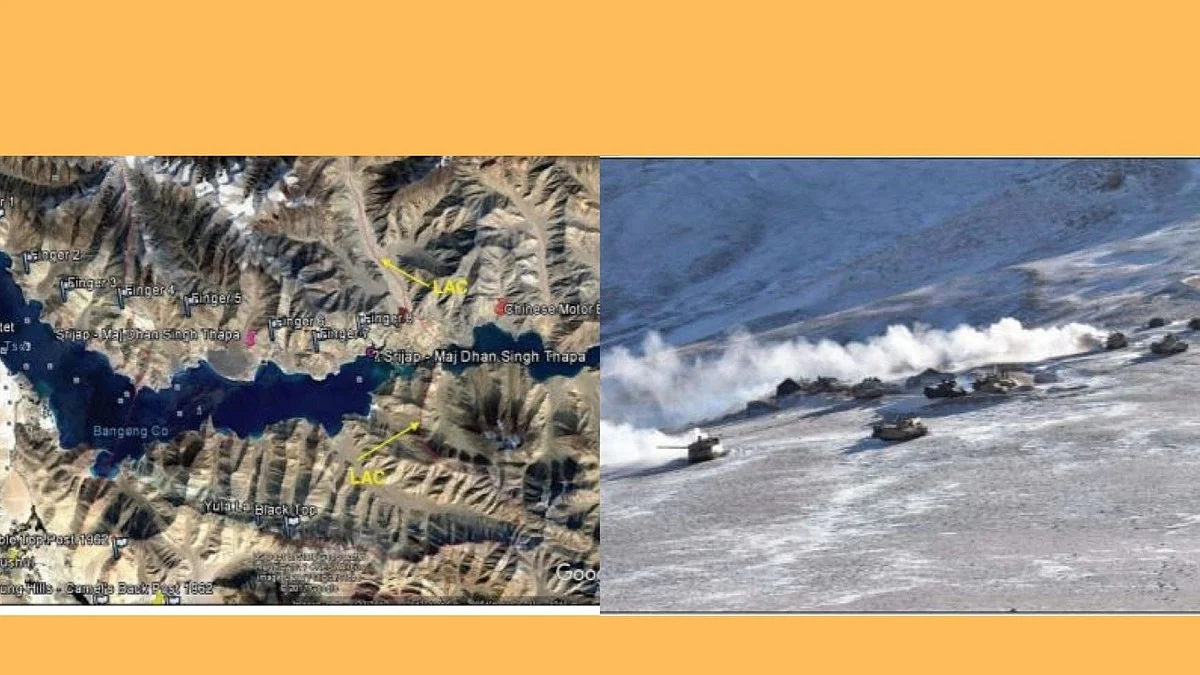

Last year, over 60,000 PLA soldiers breached the LAC (Line of Actual Control) to overrun numerous strategic features vital for India’s security. In purposeful inroads, Chinese troops brought in infantry combat vehicles, heavy artillery, light tanks, medium-lift helicopters, rocket launchers, drones and thermal imaging, and additionally created extensive support infrastructure with fortifications and encampments.

India too amassed its troops and resources in the rugged terrain that averages 10,000 feet above sea level. Buttressing the forces were the indigenously developed Light Utility Helicopters (LUHs) and T-90 tanks, armoured personnel carriers (APCs), M777 155 mm howitzers and 130 mm guns. The border was poised on a tinderbox with Indian intelligence estimating that since May, China occupied and controlled a combined area of about 1,000 square kilometres in this border region, thereby unilaterally redrawing the LAC.

An alarmed nation sought more information. How was the PLA action allowed in the first place? Was there a lapse of military intelligence? Or had the government failed to act on intelligence inputs – as had happened in Pulwama -- despite an Indian patrol having been challenged by PLA soldiers at Pangong Tso in September 2019, and China staking its claim on parts of the Galwan Valley ever since the boundary talks of 1960?

If Prime Minister Narendra Modi refrained from mentioning China by name as the aggressor, and maintained that “not an inch of Indian territory” had been ceded, what was discussed at the nine rounds of military talks? Did this reluctance to name the aggressor and denial of LAC violations give the Chinese the upper hand in the negotiations?

Though the Indian military has photographed and video recorded a measured PLA retreat at Pangong Tso following the ninth round of talks, it is to be seen if the Chinese will follow through the full agreed process. After all, similar hopes of a pullback had been roused earlier with government claiming that hostilities had been defused following an extended video call on July 5, 2020 between India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi. The two leaders had pledged “full and enduring restoration of peace and tranquillity, and to work together to avoid such incidents in future”. But after initial moves, China’s occupation forces stayed put.

Again, as the military-level negotiations continued, Rajnath Singh met his Chinese counterpart, General Wei Fenghe, on September 4 on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Defence Ministers’ summit in Moscow to discuss mutually acceptable solutions to the crisis.

A week later, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar met Wang Yi at the same venue on the sidelines of the SCO Foreign Ministers’ conclave to try and end the dispute. Their joint statement noted that both sides felt the situation at the border was not in their interest, and called for their troops to “quickly disengage, maintain proper distance and ease tensions”. The two Ministers had also spoken over the telephone on June 17 to resolve the impasse, two days after the killings of 20 of our soldiers, including a colonel, when some 350 PLA personnel attacked a unit of 100 Indian soldiers with stones and iron rods. Many more were wounded and the Chinese too suffered casualties.

Contrary to New Delhi’s repeated claims that it has extracted major concessions from Beijing, it does appear that India has ceded territory to China by agreeing to a withdrawal of its forces from areas well within its borders and to the creation of a ‘buffer zone’ that is partially within Indian territory. The implication of this is that India has failed to insist on a status quo ante that would have reinstated the captured territories.

China has thus succeeded in unilaterally altering part of the LAC, the 3,488- km Himalayan border that divides the two neighbours. The understanding reached on July 5 too had been for both sides to move back at least 1.5 km from the stand-off points, to maintain a 2-km barrier on either side of the LAC and to devise border patrolling in a manner that would avert the recurrence of any military confrontation.

Within two months of their first incursions, around 6,000 PLA troops – the strength of two brigades – had occupied extensive areas in the Galwan Valley, Chushul, Gogra, Hot Springs, the northern banks of Pangong Tso, the spurs or Fingers of Chang Chenmo, which is an eastern extension of the Karakoram range, and Patrolling Points (PP) 14, 15 and 17-A. The PLA had also traced an 80-metre-long Mandarin character meaning ‘China’ on the banks of Pangong lake alongside an expanded map of their country.

China had hitherto been intransigent at the military-level talks, not only rejecting India’s demands to withdraw, but also snubbing all discussion on the three locations they occupied in Galwan, instead claiming the entire area as theirs. New Delhi’s failure to prevent and counter Beijing’s aggression had dimmed prospects of a resolution.

In what appeared to be an attempt at opening another front for hostilities against India, China was in January reported to have constructed a village, of 101 houses, on the banks of the Tsari Chu river 4.5 km within Arunachal Pradesh. Beijing contested this, saying the construction was on Chinese territory, as it does not recognise Indian sovereignty in that north-eastern state that it calls Zangnan or South Tibet.

Just days later, PLA troops clashed with Indian soldiers at Naku La in the northern border area of Sikkim, resulting in injuries on both sides. The Indian military described the incident as a minor face-off that was resolved by commanders as per established protocols.

It is widely believed that the border conflict could well have been defused in the initial stages if the Prime Minister had reached out to Chinese President Xi Jinping. Such an outreach could have proved most opportune, especially with the military and political level talks remaining infructuous.

No less a person than former Defence Minister A.K. Antony raised a set of issues at his press conference that followed the incumbent Defence Minister’s statement in Parliament. Expressing regret that the Modi government was not prioritising national security, Antony felt that India was for the first time facing a two-front war-like situation from China as well as Pakistan.

“Why has the Modi government let down our armed forces?” he asked. “Disengagement is important, but it is a surrender by the government.” He also questioned the rationale to withdraw from PP 14 in the Galwan Valley and from the strategically important Kailash Range south of Pangong Tso, while creating buffer zones within our own territory in Depsang Plains, Gogra and Hot Springs. The Congress leader believed that when our Army had a post at Finger 4, there was no need to have withdrawn our positions to Finger 3.

The larger question remains as to the objective behind China’s push into Eastern Ladakh, especially when it had invested heavily in men and material to secure and control the areas they overran. Chinese Han culture is goal-oriented, and its military infers that if it can at will invade a territory that offers little resistance, it cannot be expected to retreat on request.

China’s military offensive in Ladakh is not merely tactical, but has a strategic intent aimed at realising specific long-term objectives. The PLA’s moves were, after all, directed by the topmost leadership, namely, the Central Military Commission (CMC) chaired by President Xi.

Nevertheless, while the ninth round of talks was held after more than two-and-a-half months since the previous meeting of November 6, 2020, both sides have now agreed to maintain the momentum of dialogue and negotiation, and hold the tenth round of the Corps Commander Level Meeting at an early date to jointly advance de-escalation.

The two sides also agreed to continue their efforts at restraining frontline troops, stabilise and control the situation along the LAC in the Western Sector of the China-India border, and jointly maintain peace and tranquility.

Views expressed are personal

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines