J&K lost but did India gain? Taking stock a year after August 5, 2019

BJP is planning to celebrate the first anniversary of abrogation of Article 35A and ‘suspension’ of JK’s special status on August 5, 2019, when the state was downgraded to two Union Territories

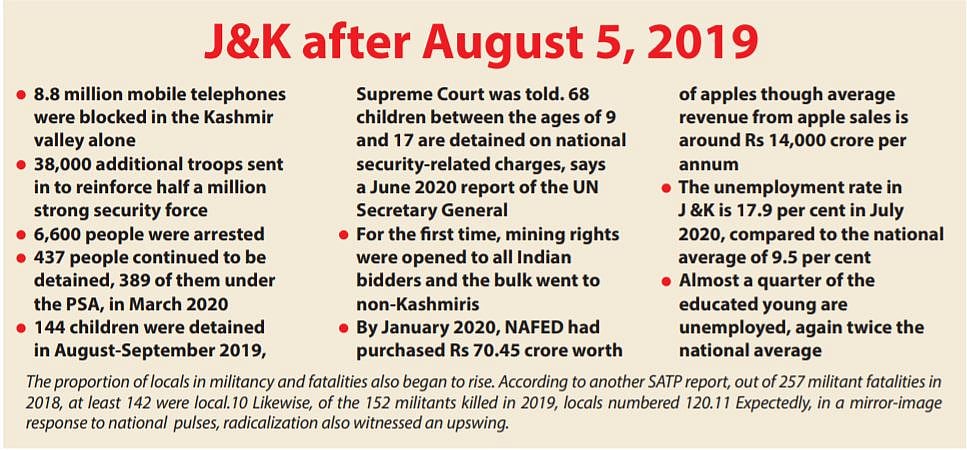

Two days after the union home ministry in July said ‘no’ to restoration of 4 G internet in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), the union territory’s Lieutenant Governor, G.K. Murmu said that highspeed internet should not be an issue, giving rise to speculation that there was change in the mood of the government.

Before that, on July 14 the government decided to go ahead with Amarnath Yatra and resume tourism after putting Kashmir under strict lockdown in view of spike in COVID-19 cases. The idea was shelved a day before the scheduled resumption on July 21.

J&K has become the latest ground for playing mind-games. The flip-flops continue to add to the confusion and uncertainty that have dogged the region since August 5, 2019 when Indian government rendered Article 370 void, abrogated Article 35A and reorganised the country’s only Muslim majority state into two union territories.

The action was preceded by rumours, the sudden halt of Amarnath yatra and tourists asked to leave the state because of a purported terror attack in the offing; the additional mobilisation of troops, selectively leaked out government orders for stocking up supplies for three months and hundreds of midnight air sorties. The sense of uncertainty vulnerability has attained permanence one year on.

BJP prepares for a mega 10-days celebration of the first anniversary of turning Article 370redundant. But despair has settled in all parts of the region, including the Hindu majority belt of Jammu and Buddhist majority Leh district of Ladakh.

Unlike Kashmir, which absorbed the sense of loss with shock and horror amidst a climate of fear triggered by astringent lockdown, massive arrests and silence enforced at gunpoint, Leh and Jammu had witnessed celebrations. Ladakh’s Buddhists had been demanding a UT status for long but for Jammu’s Hindus, the demotion from a state somewhat muted the sense of triumph over the demolition of J&K’s special status.

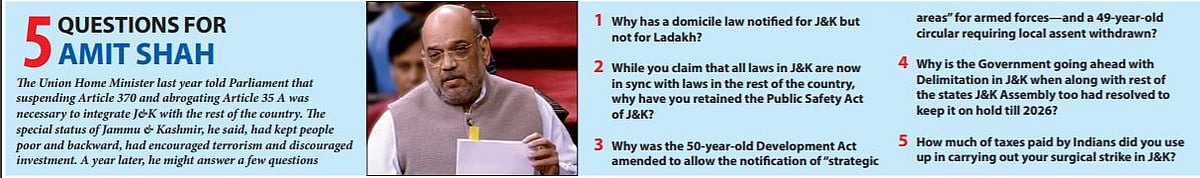

Once the spell began to wear off, both the regions have become schizophrenic. The import of the abrogation of Article 370 began to be understood only when rules and laws began to take shape in accordance with the new rules of engagement.

People of the erstwhile state would not only be losing their privileges to jobs, admissions in higher educational institutes but also land and business. The domicile law is applicable only in respect of jobs and its nature is already too relaxed as it seeks to absorb several categories of people and is likely to benefit lakhs of non-permanent residents in one go.

Unemployment levels have already pushed the youth to the brink. Additionally, with the government mulling closure of several public sector undertakings (PSUs) like SICOP, SIDCO and J&K Minerals Limited, the distress among youth is reaching an alarming level. The fears of the local youth are that they would not only be losing a good share of government jobs to new domiciles, they will also be marginalised in the job market in the private sector while PSUs will be eased out.

With respect to college and university admissions and ownership of land, even this limited protection does not exist, making J&K far more open than its neighbouring state, Himachal Pradesh, or the conflict-ridden states in India’s north-east.

Expected investments, which are likely to come more to extract natural resources, in view of the precarious law and order situation of the region, would have a deleterious impact on both ecology and the economic prospects of local residents.

In the last few months, the Indian government has been repeatedly declaring that it is creating land-banks for inviting investors from outside to set up businesses and industries in Kashmir. Pursuant to this, the J&K administration under the Lieutenant Governor has so far identified 15,000 acres of land from 203,020 acres of state-owned land in Kashmir region for industrial infrastructure development. Most of this land is ecologically sensitive because it is either part of or close to rivers, streams and other water bodies according to officials. In Jammu, 42,000 acres of state land have been similarly identified for development.

On July 24, the J&K administration approved transfer of land measuring 9654 Kanals in favour of Industries and Commerce Department for establishing Industrial Estates at 37 identified locations across Jammu and Kashmir, giving rise to concerns of shrinking the existing forest and agriculture land.

Anxieties of local businessmen, already crushed by economic losses to the tune of Rs 50,000 crores in the last one year, have been precipitated by fears of being overshadowed by ‘outsiders’. They are visibly not in a position to compete. The worries are magnified by the manner in which the sand-mining and stone quarrying contracts have been given out to businessmen from other parts of the country, who not only had better money-power to quote impressive bids but also unrestricted internet access to participate in the process.

The gradual realisation of the impact has dampened the euphoria and partially clouded the optimism in Jammu. But murmurs of protest remain muted, due to the pandemic related lockdown. The Hindu majority in Jammu had been fed on the notion that only by “showing Kashmiris their place” could nationalinterests be best served. That is an additional dilemma.

Anxieties in Ladakh are increasing with no assurance forthcoming from the government on protection of the tribal status, the likely ecological fallout of opening up the land for investments and the tensions with China at the borders but also due to the deepening of communal divisions.

The anxieties of losing jobs, land and business are common across the landscape, transcending all geographical, religious and regional divides. Added to this is the political disempowerment of the people with the erstwhile state’s downgraded political status.

While Ladakh UT will have no legislature, the limited nature of J&K UT’s assembly, whenever that assumes shape, is likely to reduce political discourse to the level of municipal matters. Could these common concerns become grounds for some solidarity? Perhaps! But few details may be significant.

The project of demographic change, inspired by BJP’s pathological hatred for Muslims and its abject intolerance to the existence of a Muslim majority region in the country, may also be a threat in Kashmir and for Muslims elsewhere, though not across the board. Added to this, New Delhi has also set into motion the process of delimitation for redefining the electoral constituencies, engendering fears in Kashmir of also losing their political domination.

In such a situation distress, divisiveness and chaos are the fruits that the country could potentially harvest.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 02 Aug 2020, 1:06 PM