Nawabs of Malerkotla in Punjab held out lessons in communal harmony since the 15th Century

Under Muslim rulers, the princely state was an oasis of communal harmony since 15th century

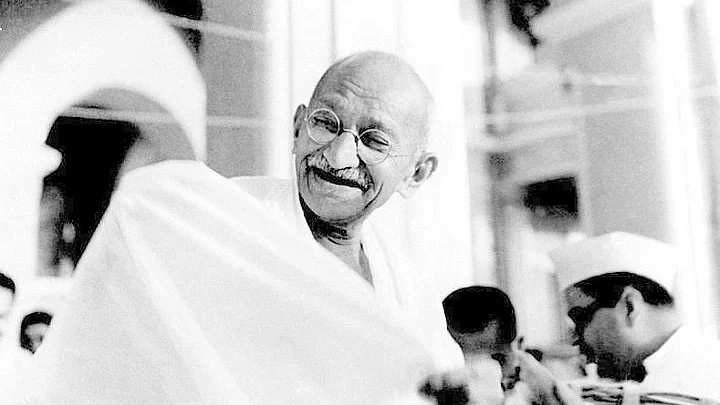

Truth and non-violence that Gandhi coalesced into the term Satyagraha and championed during India’s freedom struggle would go on to influence figures like Dr Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. But while their association with Gandhi are well-known, their echoes across India retain a capacity to surprise. One such strain comes from Malerkotla, a small Muslim princely state in Punjab.

A part of Sangrur district today, Malerkotla was a princely state neighboured today by districts like Barnala and Ludhiana, where the Namdhari Sikhs have their spiritual home in Bhaini Sahib. The Namdhari Sikhs, a sect formed in the aftermath of East India Company’s conquest of Punjab in 1849, have often been acknowledged to be among the first challengers to colonial rule in the region. Famous as ‘Kukas’, their movement was marked by ideas of non-cooperation and civil disobedience, while also encouraging vegetarianism and social reforms, especially towards women. Significantly, this happened in 1860s-70s, around the time Gandhi was born!

Soon after, during the wider cow protection movement that emerged in British India, the Namdharis participated with great zeal. In January 1872, an ox-slaughter at Malerkotla triggered a full-blown skirmish between a group of Namdhari Sikhs, Malerkotla officials and British administrators. The violence did not stop even after Ram Singh, the Namdharis’ leader, counselled restraint. This culminated in the infamous public execution without trial of over 60 people, including children, who were tied to cannons and blown away, a method reminiscent of 1857. A memorial stands at Malerkotla even today.

One reason why Ram Singh had counselled restraint could well be the connection of the Nawabs of Malerkotla with Guru Gobind Singh. Malerkotla had a history of peaceful inter-faith co-existence starting from the 15th century. The Nawabs patronised Sufi saint Shaykh Sadruddin Sadri Jahan and ‘Haider Shaikh’. Nawab Bayazid Khan invited a Chishti Sufi saint, Shah Fazal, and a Bairagi Hindu Saint, Mahatma Shyam Damodar, to bless the city of Kotla in 1657.

Haider Sheikh’s dargah continues to host a mela on the first Thursday of every month attracting devotees cutting across faiths. Above all, the residents still remember and quote the famous blessing to Malerkotla by Guru Gobind Singh. In 1705, the then-Nawab Sher Mohammad Khan, protested profusely and wrote to Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb when Guru Gobind Singh’s nine and seven-year-old sons, Fateh and Zorawar Singh, were captured and sentenced to be bricked alive by the court of the Governor of Sirhind.Notwithstanding Khan’s haa da naara, the sentence was carried out, but when the Guru heard about this protest by the Nawab, he blessed the riyasat of Malerkotla. It has acted as a public deterrent to communal violence and promoted inter-faith harmony, a reminder of an alternative possibility. Never was this more evident than amongst the horrific tragedies of communal violence, murder and forced migration during the Partition.

Malerkotla, a small Muslim princely state, surrounded by much larger Sikh states, was an oasis of peace and coexistence during those turbulent times, even as some of those neighbouring states harboured and promoted nefarious intentions. Although in the 1920s and 30s, princely states experienced far fewer riots than the provinces of British India, as shown by the research of historian Ian Copland, in 1947, nearby states such as Faridkot and Patiala and states further along like Alwar and Bharatpur were complicit in forms of ethnic cleansing.

How did this happen? An incident from May 1935 gives a glimpse into the world of Malerkotla, when clashes happened over several years over Hindu and Muslim prayer times. A katha was being recited in a Hindu household overlooking the Masjid in Moti Bazaar. This continued amicably until the katha began to interfere with the Isha (night) prayers of the Muslims. This resulted in protests from both sides, leading to public processions, hartals and deliberate noise being made during prayer times to disturb each other. After four nights of continuous tension, the state authorities decided to suspend both the katha and Isha prayers. This aggravated the tension further and led to the death of one Puran Mal in October. The state authorities responded by arresting several Muslim youths. Two of them were executed. This was considered as a rash and harsh decision by some in the Muslim community but, undeterred, the authorities went ahead and imposed different prayer times for each community. State records show how issues such as these were being politicised more so than before as well as the authorities’ awareness of the potential, harmful consequences on inter-faith relations.

From some of the correspondence to the Nawab, there is an evident sense of insecurity and mistrust from the residents and organisations representing minority populations. This series of episodes, if not managed firmly and coevally, could have flared up. What was of long-term social significance was how the culture of state-promoted pluralism survived and thrived as opposed to identity-politicking, communalised chaos and manufactured violence.

As Perry Anderson reminds us, official secularity is not meaningless, and the role of the ruling state and ideological apparatus remain crucial in maintaining law and order, as was demonstrated several times in Malerkotla.

The ruling Nawab and his officials could be more than just sympathetic to their co-religionists, but had to be mindful to the others, for a variety of reasons of statecraft even if one cynically discounts stirring social syncretism. Equally though, it was the social reception of the state’s diktats that enabled a peaceful resolution of conflicting prayer times in Malerkotla.

Gandhi could only have applauded. Today, it is again that chequered history of coexistence, inter-faith dialogue, peace and non-violence, which is required to overcome the toxic WhatsApp forwards and TV debates that do not merely communalise the public sphere but perversely incite people.

It is often this shared past of togetherness that give people hope and courage to have faith in basic humanity; sometimes going against the prevailing mood. It is not that Malerkotla has never experienced social tension; it is rather how it has managed that tension.

How is it possible for some states and societies to maintain peace and for others to remain indifferent or, worse, actively encourage conflict? Not by paying easy lip-service to Gandhi but by trying, like him, to feel the pain of others.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines