There’s little to worry over migration from Uttarakhand

Over 10 years, just five per cent of the population left Uttarakhand. The report of the Migration Commission, the only such body in the country, puts all doubts to rest

Migration or Palayan, to use the Hindi term, is a highly emotive expression in Uttarakhand. Almost every Uttarakhandi has strong views on the subject and one of the most frequently quoted saying is: Pahar ka paani aur Pahar ki jawani yahaan ke kaam nahin aate hain.

In the hills, neither water nor youth are of much use for the people living there. Both water and the young slide off early. It is in response to this strongly held feeling that Uttarakhand government appointed a Rural Development and Migration Commission last year – the first such body in the country.

The Commission has just presented its first report. I would like to commend the Commission for the large volume of data, both secondary and primary, that it has assembled in a short period of time. I cannot comment on the quality of the primary data collected by it in the absence of an examination of the survey instrument used. However, given the fact that the NSSO, which has a very high reputation worldwide as a premier survey organisation, was “consulted” lends respectability to the survey instrument.

The report does not specify, though, what the consultation with NSSO involved. The methodology followed by the report seems a combination of Rapid Appraisal and orthodox survey techniques. The former includes consultations with different stakeholders, members of the public, civil society, entrepreneurs, officers and staff of government departments, media, industrialists and others "for their perception on migration from the rural areas; The latter is based on a specially designed questionnaire circulated at the Gram Panchayat level. We are left guessing how well prepared and trained the staff was to undertake such a task. A serious shortcoming of the report appears to be that the data collected by it do not permit the analysis to discriminate between migration in general and forced or distress migration. This distinction is crucial.

Migration is a phenomenon that has been part of human life since time immemorial. In fact, if it were not for migration, homo sapiens would still be living in eastern Africa. What should rightly be a matter of concern is forced or distress migration. Preventing or minimising forced or distress migration should be the primary concern of governments.

Over a ten-year period the Commission estimates the total number of semi-permanent migrants as 3,83,726 from 6,338 Gram Panchayats, and permanent migrants as 1,18,981 from 3,946 Gram Panchayats.

In fact, migration has been a feature of agri-pastoral mountain areas all over the world largely because of the fragile resource base which is not adequate to support rising population in traditional occupations. Thus, migration acts as a safety valve; otherwise they would be swamped by a large population dependent on meagre resources, resulting in widespread poverty.

There are only three ways out of this trap:

• ‘Agricultural involution’ to use the process described by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz in relation to intensive cultivation of rice paddies in Java (Indonesia) resulting in “increasing the labour intensity in the paddies, increasing output per area but not increasing output per head”. This can only result in intensification of poverty. The process of involution is ruled out in Himalayan areas because the land, soil and water resources are not such as to permit increasing labour intensity beyond what already prevails.

• Migration in search of better livelihood opportunities. This is a strategy which the people have al ready been choosing. In fact, this is not a new phenomenon. It has been there for many years as witnessed by the large population of hill dwellers in different parts of the country and working in diverse fields. The process may have been accelerated recently with improvement in transport and communications – roads, mobile phones, television, internet etc. – which encouraged mobility.

• Technological change involving transition to a different and higher form of economic activity a la Switzerland, Austria and other industrialised countries with mountain areas. This strategy presupposes a highly developed educational and technological infrastructure and a large pool of highly trained manpower. Our mountain areas are still quite far from this situation.

Two broad conclusions emerge from a quick study of the report. One, seen in the wider national perspective, the issue of migration is no different, or of a different order from the rest of the country.

Secondly, as to the reasons for migration and its impact on local economy, the report does not tell us anything new; it only confirms what is already known.

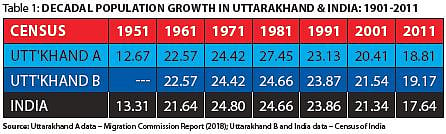

The major contribution of the report is that it supports some of these assertions with micro level data. The data on population growth between 1901 and 2011 culled from the Commission's report and from the Census indicate the following:

After an initial period of growth of 8.2 per cent between 1901 and 1911, the population of the state declined by 1.2 per cent in the next decade, perhaps on account of the combined effect of World War I and the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 which is estimated to have killed about 11.5-17 million people in India – depending upon which estimate we rely on.

• Thereafter population of Uttarakhand grew steadily, with a slight dip in growth between 1941 and 1951, occasioned perhaps by the partition of the country in 1947, till it peaked at 27.5 per cent in 1981.

• The next three censuses after 1981 show a steady decline in the growth rate. It would however not be quite accurate to ascribe this decline to migration. It is most likely part of the secular decline of population growth in response to economic growth and social change witnessed as part of the thrust of modernisation. This is supported by the fact that decadal population in Uttarakhand generally follows the trend at the national level.

The report reproduces NSSO data of 2007-08 on rate of migration calculated as migrants per 1000 population in different states. This shows that Uttarakhand with a score of 486 ranks second highest among the 17 States for which data is presented. The highest rank is that of Himachal Pradesh with a score of 532.

Other States that score high i.e. more than 400 are Chhattisgarh (452), Odisha (442), Maharashtra (421) and Andhra Pradesh (400).

Once again Himachal Pradesh tops with a score of 615 followed by Uttarakhand with a score of 594. The figures for some other states are, in descending order, Chhattisgarh (590), Odisha (567), Punjab (565), Madhya Pradesh (523), Bihar (497), Maharashtra (493), Andhra Pradesh (467), and Kerala (428).

Interestingly, in all states, female migration is much higher than male migration. Female migration, it may be mentioned, is in most cases marriage-related rather than based on a search for better economic opportunities, whether arising from "push" or "pull" factors.

Male migration rate remains highest in Himachal at 455 followed by Uttarakhand at 397. However, the rate of male migration in Uttarakhand, though higher, is not excessively higher than some other States like Maharashtra (356), Andhra Pradesh (333), and Chhattisgarh (330).

Two tentative conclusions emerge from these data: (i) though mi gration from Uttarakhand is higher compared to many states, Uttarakhand cannot be considered unique in terms of the incidence of migration; the magnitude is somewhat similar in many other states as well; (ii) The rate of migration – both male and total – is much higher in Himachal Pradesh, yet it is not generally considered as large an issue there as it is in Uttarakhand.

The report classifies migration as semi-permanent and permanent. Semi-permanent migrants are defined as people who live outside the state temporarily for earning a livelihood and keep visiting their home at regular intervals. Permanent migrants, on the other hand are people who have moved out of their villages permanently, or who have sold their land, or whose lands have been left uncultivated, or whose houses are locked or who visit their village only rarely.

Over a ten-year period the Commission estimates the total number of semi-permanent migrants as 3,83,726 from 6,338 Gram Panchayats, and permanent migrants as 1,18,981 from 3,946 Gram Panchayats.

Since semi-permanent migrants, as the name implies, are not a permanent loss to the State, it is only the permanent migrants that should be a cause of concern for those worried about the phenomenon. A figure of 1,18,981 in ten years or an average of 11,898 per year from 3,946 Gram Panchayats need not be a cause of too great an alarm. It works out to an av erage of 30 per Gram Panchayat over ten years or just 3 per year.

Looked at in another way the number of permanent migrants over a ten-year period as a percentage of the 2011 population of the state works out to just 1.18 per cent and of semi-permanent migrants to 3.80 per cent. The two together constitute just about 5 per cent of the State's 2011 population.

Given the state average of 30 permanent migrants per Gram Panchayat in ten years, we find that Gram Panchayats in two districts – Bageshwar and Pauri – are similar or quite close to the state average. In five districts – Rudraprayag, Tehri Garhwal, Chamoli, Champawat and Dehradun – the number of permanent migrants is higher than the state average with the highest number being in Dehradun (53). The remaining six districts fall below the state average with the lowest number being, not surprisingly, in Udham Singh Nagar and Haridwar.

The real surprise comes from the figures for Pauri and Almora on one hand and Dehradun on the other. The former two districts are generally known to be the ones with the highest rates of migration as evidenced by the fact that they had negative rates of population growth between 2001 and 2011. The above table shows the rate of permanent migration in Pauri Garhwal to be almost similar to the State average, while in Almora it is much lower.

Dehradun district, which is generally understood to be attracting in-migrants comes as a real surprise as it has the highest rate of permanent migration in the state. The answer to this conundrum probably lies in the fact that while the Doon valley receives migrants, the Jaunsar-Bawar region sees a reverse process.

The paradox underlying the situation in Pauri Garhwal and Almora is not resolved by including data on semi-permanent migrants. Thus, we find that the figure of semi-permanent migrants in the state over the ten year period comes to 60, whereas in Pauri Garhwal and Almora it is much lower – 46 and 52 respectively.

Data on migrants over a ten-year period as a percent of the 2011 population of the respective district further clarifies the situation. What emerges from the data is the fact that the four districts, two of which viz. Udham Singh Nagar and Haridwar, lie predominantly in the plains and the other two viz., Dehradun and Nainital have substantial plain areas, have the lowest rates of both permanent and semi-permanent migration.

Based on these figures, following conclusions can be drawn:

*The rate of both permanent and semi-permanent migration is higher in the mountain districts as compared to the plain districts as well as the state aggregate, the one exception to this pattern being Uttarkashi in respect of permanent migration;

*The rate of both permanent and semi-permanent migration in Almora and Pauri Garhwal, the two districts with negative population growth between 2001 and 2011 is not too different from that of other mountain districts even though the rate of permanent migration is highest at 3.72 per cent in Pauri Garhwal, while in Almora it is quite modest at 2.60 per cent; semi-permanent rate of migration in Almora (8.61 per cent) is higher than in Pauri Garhwal (6.91 per cent);

*Overall the rates of permanent and semi-permanent migration in the state are rather modest, and certainly not such as to cause undue alarm about migration resulting in depopulation.

(The author is Honorary Director, Doon Library & Research Centre)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines