Why Savarkar cannot have a place among freedom fighters and why ICHR must take him down

He was no revolutionary because after he was released following his pledge of loyalty to the British crown, he was confined to Ratnagiri district and barred from political activities

Having argued that exclusion of Nehru’s photo from the web poster of the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), meant to celebrate 75 years of India’s independence was a distortion of history (NHS, Sept 19, 2021 issue) and brought only disgrace to the high institution, I wish to record that the inclusion of Vinayak Savarkar’s photo in the said poster is also, likewise, a distortion of the past and is equally reprehensible.

Savarkar was indeed a writer and a scholar in his own right and later president of Hindu Mahasabha for several years. However, he played no role in India’s struggle for independence. He hardly finds any mention, even in references, in the countless books written by renowned historians on contemporary Indian history, especially those that record the events of the struggle for independence. Interestingly, he himself never claimed to have done so.

Those who worship him and believe in his ideas are entitled to do so. However, an august body like the ICHR cannot be allowed to distort history to sub-serve what is politically expedient for the ruling dispensation.

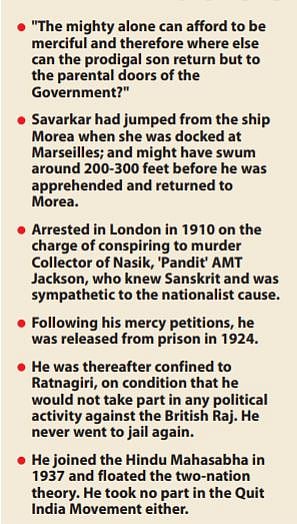

To begin with, Savarkar had no time to fight for India’s independence. He was arrested in London in July 1910; was brought to India and sent to the Andaman Islands for detention “for life”. He was then brought back to the Indian mainland in 1921 and released from prison only in 1924. Thereafter, too, he was confined to Ratnagiri town in Maharashtra, under a pledge that he would not take part in any political activity detrimental to the interests of the British Government, a pledge that he religiously honoured till the British rule lasted.

Mind you, refraining from such political activity included refraining from taking part in the freedom movement! In 1937 he joined the Hindu Mahasabha after which he propagated his own brand of the Two-Nation theory. Nevertheless, a halo has been created around his personality that he was a great revolutionary and had fought for India’s independence.

Savarkar had no intention either to fight for the independence of the country, as is apparent from the several apologies-abject apologies and mercy petitions he submitted to the British Government, the first one within six months of being in jail.

In his mercy petition dated 14 November 1913 that he submitted to the Home Member of the Governor General’s Council, Sir Regiland Craddock, when the latter visited Andaman, Savarkar mentions the solitary confinement and hard penal servitude he had been subjected to and pleads for his removal from “D” class status and asks to be shifted to an Indian jail, where he could earn remission and where his relatives could visit him. Towards the end of the petition, he says:

“Therefore, if the government in their manifold beneficence and mercy release me, I for one cannot but be the staunchest advocate of constitutional progress and loyalty to the English Government which is the foremost condition of that progress.” Finally, “I am ready to serve the Government in any capacity they like, for as my conversion is conscientious so I hope my future conduct would be. By keeping me in jail nothing can be got in comparison to what would be otherwise. The mighty alone can afford to be merciful and therefore where else can the prodigal son return but to the parental doors of the Government?”

On 22 March 1920, a Savarkar supporter, G.S, Khoparde, tabled questions in the Imperial Legislative Council, one of which read “Is it not a fact that Mr Savarkar and his brother had once in 1915 and then in 1918 submitted petitions stating that they would, during the war serve the Empire by enlisting in the Army, if released and after the war make the reform Bill a success and stand by law and order?”

Savarkar, citing his illness, had begged for “a last chance to submit his case before it was too late”. To this, the Home Member William Vincent disclosed that Savarkar had recovered from dysentery five months earlier and his life was not in danger. (Quoted by A.G. Noorani in 'Savarkar’s Mercy Petition', Frontline, April 8, 2005)

In his petition, Savarkar cited the cases of fellow prisoners, Aurobindo Ghosh’s brother Barin and another convict Hem to compare himself favourably against them, saying they had confessed that one of the objects of their conspiracy was “the murders of prominent Government officials… they had even in Port Blair been suspected of a serious plot”. Also, “Sanyal was a lifer, but was released in four years”. Thus, he pleaded for his loyalty by implicating others. (ibid)

Savarkar assures the Government of his sincerity. He says, “I am sincere in expressing my earnest intention of treading the constitutional path and trying my humble best to render the British dominion a bond of love and respect and mutual help. Such an Empire as is foreshadowed in the Proclamation wins my hearty adherence”.

He also guarantees his future good conduct if he is released. “I and my brother are perfectly willing to give a pledge of not participating in politics for a definite period that the Government would indicate. …This or any pledge, for example, to remain in one province or reporting to the police regularly after our release any such condition would be gladly accepted by me and my brother.” (ibid) Savarkar signed his petition as “I beg to remain SIR your most obedient servant, Sd/- VD Savarkar (Convict No 32778).

Much has been made of Savarkar’s escape from British custody by his jumping off a ship. Many believe he escaped from jail. I remember our Marathi teacher, Mr V.S. Mule telling us how Savarkar had jumped from a ship and swam across the sea, giving the impression that he had swum across the Arabian Sea to escape from British custody.

In fact, he had jumped from the porthole of the merchant vessel Morea when she was docked at the French port of Marseilles and might have swum across around two to three hundred feet where he was captured by a French police officer on the dock who returned him to Morea. The police officer reported that the prisoner went “peaceably” with him. Certainly, not the act of a revolutionary. ['Report of the International Awards'-the Savarkar Case-(Great Britain and France); 24 February 1911 (Vol XI pp243-255)- UN copyright e2006].

It is also pointed out by Savarkar’s supporters that he had to endure a far more rigorous prison term than Nehru or Patel had to. But this was so because the charges levelled against Savarkar that led to his arrest in London involved his alleged involvement in conspiring to murder A.M.T. Jackson, then Collector of Nasik, who was shot dead in a theatre on 21 December 1909. Nehru and Patel were charged with no such crime.

Ironically, Jackson was “sympathetic towards Indian aspirations”, was a student of Sanskrit and an Indologist and a historian. He was popularly known as Pandit Jackson. [Bombay High Court. 'Nasik Conspiracy Case' Archived from original (2009-04-09)].

The afore mentioned facts, especially the demeaning mercy petitions submitted by Savarkar, the suppliant language he uses in the petitions reveal the absence of any revolutionary fervour in him, not the defiance of a revolutionary and a freedom fighter. His willingness to implicate other jail inmates, namely Barin, Hem and Sanyal in order to save himself indicate lack of any scruples on his part. The tone of his petitions suggests he was conscious of his guilt that he had committed a crime. It is also clear that he was loyal to the British Empire and had no inclination to see its end. Consequently, he did not participate in the freedom struggle, including the Quit India movement.

Then, why does his photo adorn that poster meant to celebrate seventyfive years of independence? Honour him for what he was- an ideologue, who propounded the controversial and divisive theory of Hindutva. One cannot claim he fought for India’s independence. At least the ICHR should not!

(The writer is an independent commentator and researcher. Views are personal)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines