Tracing Adi Shankaracharya’s philosophical footprints

At a time when those who follow Hinduism have to work hard to prove that they are indeed ‘good Hindus’, rather than ‘just’ Hindus, Pavan Varma’s book should be made mandatory reading

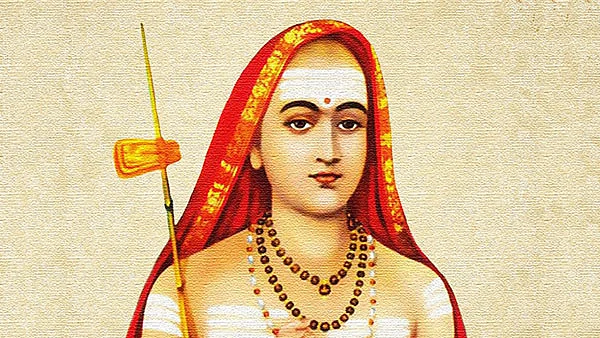

Adi Shankaracharya, revered as the Jagad Guru, is said to have travelled from his birthplace in Kerala to Kedarnath in the Himalayas, where he breathed his last at just 32 years of age. He is said to have all the signs of being a prodigy, memorising the scriptures and showing signs of being a philosopher and ascetic from an early age. He travelled across the land seeking the meaning of the ‘ultimate truth’ and established maths, or monastic orders, in Sringeri (south), Dwarka (west), Puri (east), and Joshimath (north). In establishing these centres of philosophical and spiritual learning, the saint-philosopher connected four corners of the land at an intellectual and philosophical level.

Author Pavan K Varma, a former diplomat, politician, now takes his readers along on a similar journey in modern times. His research led him to many of the places the saint himself would have travelled, stayed, taught and debated at. Varma begins in Kerala, at Kaladi, Adi Shankaracharya’s birthplace. The author describes this journey and the destination much like a travel writer. He reports in detail on what it looks like now, perhaps with a hint of disappointment at places, when one imagines what the birthplace, and the other landmarks of the revered seer’s life and teaching could have looked like.

During his travels, the author also undertakes a philosophical trek, and talks about the incidents from Adi Shankaracharya’s time that are said to have occurred in or near each of those places. In his preface to the book, Varma is candid about his reasons to undertake this massive project: “…most Hindus, while practicing their faith in their own way, are often largely uninformed about the remarkable philosophical foundations of their religion. Hinduism as a religion is inseparable from Hinduism as a philosophy.”

Varma is candid about his reasons to undertake this massive project: “…most Hindus, while practicing their faith in their own way, are often largely uninformed about the remarkable philosophical foundations of their religion. Hinduism as a religion is inseparable from Hinduism as a philosophy.”

According to him, those who are satisfied with the external, obvious, and perhaps ritualistic, practices only, are doing a disservice to the great religion they follow. Varma’s own visits to the religious places, mentioned in the book, come across as personal pilgrimages too, and not just trips undertaken for research material. In one section, he shares how he changed into a length of unstitched cloth in accordance with the math’s rules before he met its current head. He describes the delicious south Indian meal of sambar-rice, and the rich dessert, and wonders how Shankaracharya would gave reacted to the sweeter flavours of the food served in Gujarat: thoughts that come to the fore when you are immersed in the moment itself, and not too focused on the result of the meetings and journeys. The life, travels and teaching of the seer, are brought to life and punctuate the modern day research trip.

The research, and there are hefty sections of it, does form the substance of this title. Those portions read a lot like academic papers, produced by diligent students burning the midnight oil to make their dissertations the finest in the university. And, while the sections with that academic tone and tenor will work for amateur scholars, they may fail to hold a casual, or younger reader just beginning to explore the world of philosophical writings. Perhaps this book is not for them to read just yet, even if it will look good on a coffee table anyway, thanks to the lovely cover illustration by Mohit Suneja.

However, there is chapter that may intrigue them too. Titled ‘The Remarkable Validation of Science’, it is likely to draw much attention, especially from those interested in scientific theories and principles. It talks about how Shankaracharya’s writings show how he envisioned what modern scientists call cosmology, quantum physics, neurology. Though Varma adds a disclaimer and says that this is not a part of an agenda to “promote” Hinduism or ancient India.” He adds that Hinduism itself has many strands of thought and not all of them “validate what science is telling us today.” Discussions on philosophy and science are almost always the most vibrant and have the potential to turn volatile at the slightest nudge. It is interesting to read the author’s presentation of the two.

The section that presents bhashya, Shankaracharya’s commentary on the Bhagwad Gita, is beautiful. The author has selected translation by A. Madhava Shastri, done in the early 1900’s. It is clear and simple, even to a non-academic, general reader. The seer’s views on each stanza of the holy book are also presented simply. Varma has chosen the anthology of the seer’s writing with the care and sensitivity of a devotee.

At a time when those who follow one of the greatest religions of the world have to work extra hard to prove that they are indeed ‘good Hindus’, rather than ‘just’ Hindus, books such as these should be made mandatory reading. It will serve two great purposes: first it will keep you offline for a considerable period of time, and second, it will make you rethink the fact that religious philosophies need not have a singular, universally accepted meaning.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines