Translation of Faiz’s poetry falls into trap of transliteration

<i>The Colours of My Heart</i> by Baran Farooqi introduces English readers to Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the great Urdu poet of the 20th century, his life and enduring legacy

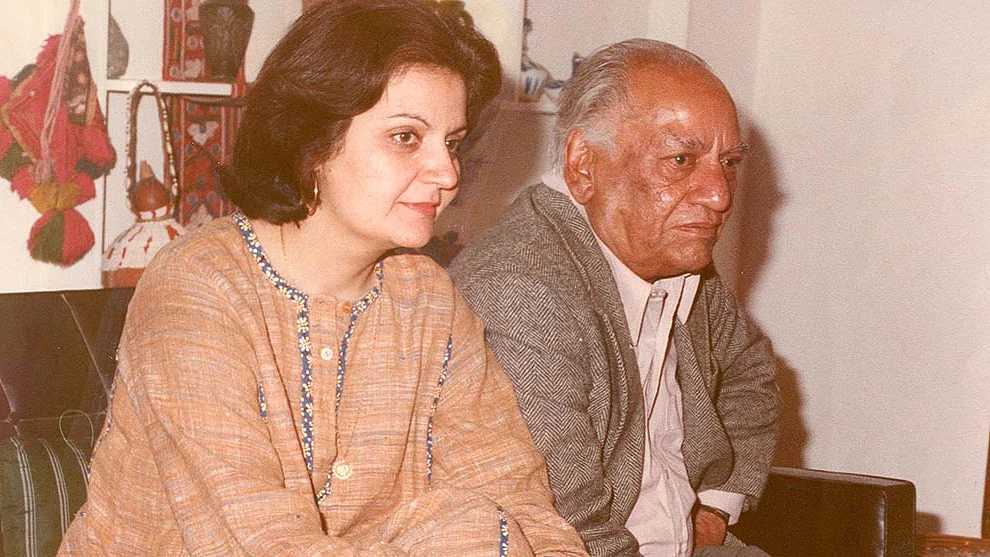

Faiz Ahmed Faiz was in jail in 1952, his eldest daughter Salima Hashmi recalled, when his book, Dast-e-Saba (Hand of Breeze) was released. “Whenever he would write a new poem in jail and send it out, it would invariably make news. We organised a function where my sister Muneeza and I distributed copies of the book amongst the participants. We spotted many wiping their tears as they read our father’s new book. It surprised us. It made us believe that our father was some sort of a magician, albeit one who weaved magic with his words,” she told the writer in 2011, when she was in Jammu to take part in one of the several functions in India to mark the centenary of Faiz.

The magic of the twentieth-century poet hasn’t waned even after several decades. While singers continue taking pride in crooning poems of the romantic rebel, his fiery verses remain a source of inspiration to those who fight tyranny and injustice. He is a poet who chose self-imposed exile for several years and for whom going to jail was like falling in love again. His scintillating ghazals and nazms haven’t ceased to bring solace to lovelorn hearts even today.

There is a growing body of literature, which celebrates Faiz’s lasting legacy of poetic work and now we’ve another addition: The colours of my heart. It’s a compilation of 57 poems from eight books of the great poet, in Roman Urdu and their rendition into English by Baran Farooqi—who teaches English at Jamia Millia Islamia in New Delhi. The book also has an illuminating introduction to Faiz written by Farooqi.

In her new book—published by Penguin Random House—she has selected poems which are elegantly lyrical, moving and invariably evoke powerful imagery with a touch of surrealism. Many of them radiate love and compassion while some make political statements in a very subtle manner.

“Today, when the word is in danger…when the dignity of the individual is at stake and the freedom of speech much at risk of fast becoming an obsolete concept, we need the poetry of Faiz more than ever before,” states Farooqi when introducing the poet. “Faiz stood for the dignity of man, the holiness of pain, the constructive power of the word and the sanctity of individual belief. He will always be needed, and that is his triumph and our tragedy.”

Though the book reflects Farooqi’s emotional connection with Faiz’s poetry—as the title of her book suggests—but at times, she does tend to walk into the trap of transliteration. She does take liberty while giving expressions to original metaphors in English and misses some of the nuances. Just like many ace singers who have added a new dimension to Faiz’s poetry in their rendition, Farooqi too could have enhanced the essence of some poems.

Most of the poems in this book have been composed, sung and translated into English umpteen times. Sample some of them—which feature in The colours of my heart, and Farooqi’s attempt at the translation:

The title of a poem, Tanhai has been translated as ‘solitude’, which doesn’t seem to be an appropriate word for it. The poem describes the condition or state of a lover forsaken by her/his beloved. Similarly, in her translation of the poem, she has rendered Khvabida charaag into ‘still lamps’ instead of ‘dreamy lamps.’

In fact, Tanhai talks about a person who is asking his own desolate heart, while waiting for someone: “Did somebody come again, sad heart?” And gets the reply: “No, nobody.” But before the poet reconciles with the reality and console himself stating: “Lock your sleepless doors, no one, no one’s going to come here now,” the poem beams a striking yet depressing image of loneliness:

It must be a wayfarer somewhere, he’ll go away

The night is past, the stardust begins to dissipate

The still lamps in the mansions begin to falter

Weary of waiting, all the roads are now in slumber

The dusty road, unsympathetic, has clouded all traces of footprints

In the rendition of another masterpiece, Zindaan ki ek subh (A morning in the prison house), Farooqi has translated mai-e-khvab into ‘wine of sleep and not ‘wine of dream’. Unfortunately, she also becomes oblivious to metaphors like Jaam ke lab (lips of the goblet) and tah-e-jaam (bottom of the goblet). Again, she has taken liberties to change the poetic expression of a few lines such as this one: Chaand ke haath se taaron ke kanwal gir gir kar… Here she renders taaron ke kanwal into ‘star lamps’ and not ‘lotuses of stars’. The wrong depiction of the metaphor has a bearing on the subsequent line as lamps can neither bloom nor wilt.

Among other free-verse poems in her book: Bol (Speak) has almost become an anthem for upholding right to freedom of expression. Another poem, Subh-e-Azaadi (The Dawn of Freedom)—which bemoans partition of Indian sub-continent and ensuing carnage, but becomes a clarion call for revolution—has also found place in her book.

Incidentally, among his peer poets, Faiz had this unique privilege that many of his poems got translated into multiple languages of Europe and Asia during his life time only. This book—in a nutshell—introduces English readers, who’re unacquainted with Faiz—a poet who is as much loved in Pakistan as in India—to his incredible life and enduring legacy.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

- Pakistan

- Jammu

- Jamia Millia Islamia

- Urdu

- Penguin Random House India

- translation

- Faiz Ahmed Faiz

- Baran Farooqi

- Salima Hashmi

- Muneeza

- twentieth-century poet

- ghazals

- nazms

- literature

- surrealism

- transliteration

- metaphor

- legacy