Viewing citizenship through the lens of gender

This collection of articles examining ‘gendered citizenship’ brings a feminist lens into study of citizenship, and the ways in which performance can represent, critique and construct political action

This collection of articles examining ‘gendered citizenship’ emerged from a two-year research project conducted by academics at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India and the School of Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Warwick, UK. The project itself grew out of an eight-year collaboration, and this has allowed an infusion of ideas from different perspectives and disciplines into the various studies included here. While bringing in comparative perspectives and some experiences from other parts of the world, it is mainly focused on the situation in India. Bringing a feminist lens into the study of citizenship, and the ways in which artistic performance can represent, critique, and construct political action, this is a book that has multiple facets and provides ample basis for discourse and further research.

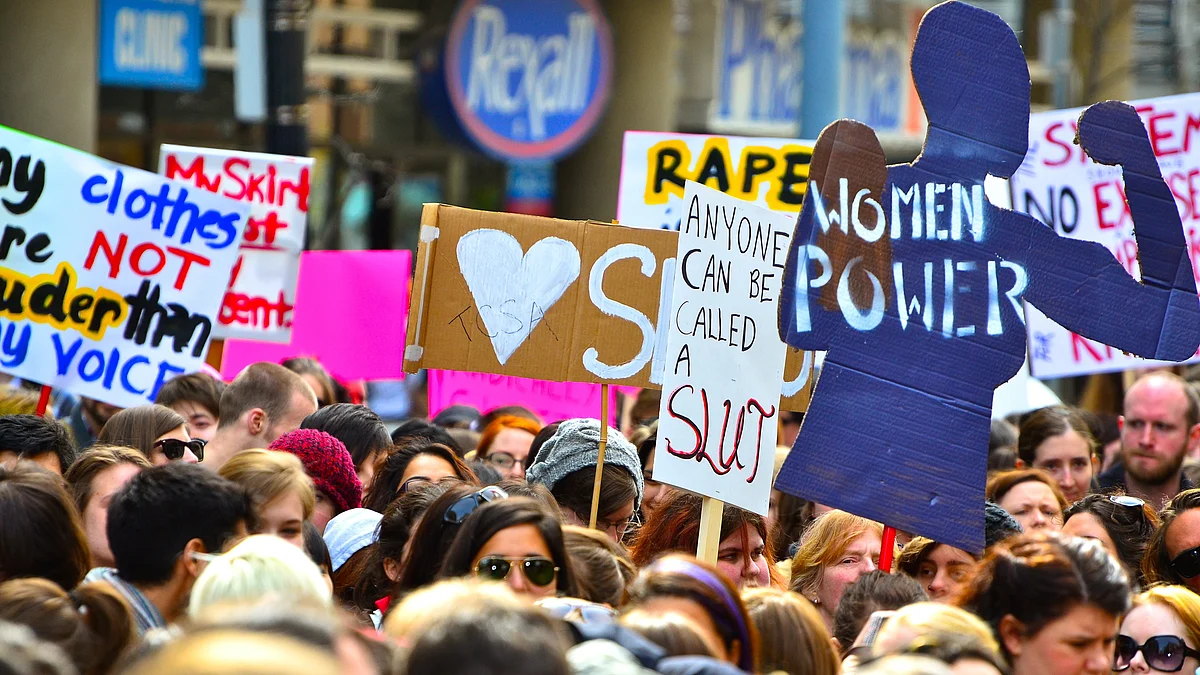

Citizenship is sought after for the legal security and sense of place it confers, although as Shirin Rai puts it, ‘While struggles for belonging may lead to struggles for and attainment of citizenship, citizenship does not automatically generate belonging. ….Citizenship may be attached to the state, belonging has more complex roots in the diverse social spaces of everyday life – local, national and global’. Women as citizens may confront the state through street protests, expressing agency while protesting violence and patriarchy. More nuanced critiques are found in art, theatre, dance, circus acrobatics. The book contains many interesting examples of the ways in which art can be performative politics.

Performance has the potential to question and dislodge the more stable narrative of citizenship that emerges from pursuit of law alone. Shrinkhla Sahai discusses how performance art, which emerged in the 1960’s in the West, and which emphasizes participation by spectators, has been seen in India since the 1990’s; and she makes the important point that it largely remains within the ‘safety net of protected spaces’, thereby limiting its likely impact. Performance offers an alternative strategy of resistance, but remains limited in its impact if unable to move into a larger public space.

Susan Haedicke discusses the activism of the ‘Glasgow Girls’, starting with a local event in Glasgow, Scotland in 2005, leading on to a major human rights campaign that not only helped to win the release of the family that inspired the protest, but also change the Home Office policy of dawn raids. Various artistic versions have ‘shaped the many events into a recognisable David and Goliath tale’, and also changed the way that the public imagination looks at asylum seekers. This story is particularly interesting for the synergy between local activism and a national campaign, between actual events and artistic imagination and performance, performance through art and change in the stable narrative of citizenship.

The book provides evidence of the potential of performative art to influence public discourse and imagination

Other examples discussed in the book seek to bring to the front the voices and experiences of invisible groups, or those who feel estranged even while formally included, as in partition literature (which looks at partition from the perspective of those who lived through it), queer politics, or the migrant maid whom no country claims. Amrita Nandy and Sneha Banerjee argue that ‘women’s citizenship is deeply tied to their bodies’ and official entitlements reflect assumptions regarding gendered roles. Anuradha Kapur discusses theatre as a political space. Ranjani Mazumdar suggests that as rape acquired greater visibility in cinema, it offers a powerful way to question the law.

In a sense, the book provides powerful evidence of the potential of performative art to influence public discourse and imagination, and the formal processes and trappings of legal citizenship. It raises several questions too. As the book points out, performance art in India is relatively new. There is a tradition of dissent in ‘traditional’ art as well. Looking at these newer art forms, it is of interest to know who participates, and how their art is received by a wider public. It is also not entirely clear whether all performance art conveys a similar politics, and message of protest, because there could be performative artists of varying political hues. It has been pointed out that while knowledge in the natural sciences builds upon previous work, social science research can be stand-alone. If we view performance art as an academic discipline, the ways in which different artists connect with each other’s work and build upon it, so to say, so that the cumulative message and impact is greater would be useful to understand.

On the whole this book opens some new dimensions and perspectives to the study of gendered citizenship. Its particular focus, of looking at questions of citizenship through the lens of artistic manifestations and performance, is a unique and a new approach. While it advances the academic study of citizenship, it will also be useful for gender researchers. Art, even performance art, often remains distinct from academic work. By bringing it centrestage, so to say, the book creates a new space for further debate and reflection.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines