The Press after Nehru

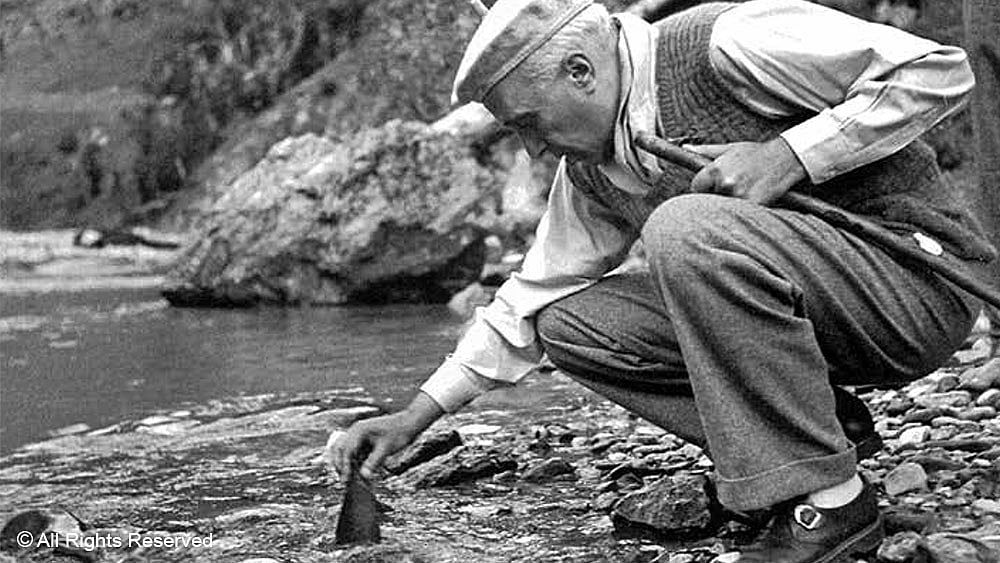

<b>This tribute by National Herald’s </b><b>former editor </b><b>late M Chalapathi Rau appeared in Economic Weekly—now EPW</b><b>—in July 1964, </b><b>two months after Jawaharlal Nehru passed away</b>

[The Economic Weekly: On the National Herald from the day it was founded in September 1938 M Chalapathi Rau was close to Jawaharlal Nehru, the Chairman of its Boards of Directors till he became Prime Minister. When the National Herald was restarted towards the end of 1945, after an interregnum during which it had been shut down by the British, Chalapathi rejoined it as Joint Editor, and since July 1, 1946, he has been its editor. Though his formal connection with the National Herald ceased, Pandit Nehru maintained dose touch with its Editor, without ever interfering in editorial policy or working. In his message to the Silver Jubilee number of the National Herald last September, Pandit Nehru wrote:

"In spite of the abundance of newspapers in Delhi, I have seen the Herald daily here and have often read its editorials. Under the able guidance of its editor, Shri M Chalapathi Rau. it has kept up a high standard. While generally favouring Congress policy, it has maintained an independence of outlook which I have appreciated".

In his speech at the Silver Jubilee function, Pandit Nehru said: "People think it is my paper. It really is Chalapathi Rau's paper; he has made it what it is."]

Jawaharlal Nehru had a high conception of the place of the press in national life both during the freedom struggle and after freedom. It was a part of his liberal outlook and a part of his upbringing in Liberal England, when Northcliffe was making a big noise without yet displaying the insufferable Bonapartism of his last days but threatening the press with new, if many of them false, values. To Jawaharlal Nehru, who was accustomed to self-inquisition and self-criticism, criticism was the breath of life and had to be tolerated. No other public man of his standing tolerated criticism as much as he did. It was the democratic way of life, and life itself.

To him, journalism was neither history nor literature in a hurry; it was a part of action, political action, social action. There was a literary touch in the best that he wrote and he always spoke and acted with a historical sense. But he did not consider himself a writer or a historian; he was a man of action who wrote because his writing was another side of his self-expression and helped him to be a man of action. Whenever he sat before me at my table, asked for a pad of paper, and wrote articles, without hesitation, without a scratch, without the need for revision, he seemed to be not composing, fumbling over words of riddling with them, but expressing himself in a straight, simple style, with an uncomplicated syntax and with a sense of rhythm. He did not write as the Kingsley Martins and Malcolm Muggeridges write: he wrote as a man who makes history alone can write and he will be read when they will not be read. The manuscript was always exquisite, as copy near-perfect. He wrote unsigned articles, signed articles, and once he reported his own speech at a Bara Banki meeting late at night. It was the Puck in him.

Respect for Press Freedom

During the freedom struggle, he wrote with great feeling, and he would always tell us that strong writing was not abusive writing; it could be simple. Style attracted him, and in newspapers of his day, he missed style, that something which spoke of personality and character. At least, he expected clear thinking, clear expression, and sincerity of feeling, if not conviction. His writing, whether it is classified as literary or journalistic, conformed to his high standards, whatever the perplexities caused to some people by the perenthesis and periphrasis of his latter-day speechmaking.

Jawaharlal Nehru had high professional standards and sought: them in the daily or weekly operation of press freedom. He always advised us to refer to the British authorities debatable news items, with disputable facts, coming from Congress sources. Would not the British or any other authorities deny facts that went against them? It did not matter, he said; they should be given their chance. If they gave their version, it should be also published. This was even in the old days. The soundness of his advice was proved when for a one-sided version, emanating from Congress sources and carelessly edited and published, the editor had to go to jail for criminal libel.

To Jawaharlal Nehru, who was accustomed to self-inquisition and self-criticism, criticism was the breath of life and had to be tolerated. No other public man of his standing tolerated criticism as much as he did. It was the democratic way of life, and life itself.

Should the editor apologise? The directors were fumbling and the editor did not know what to do. From prison, Jawaharlal Nehru sent instructions that the case must be fought, and if the editor was sentenced, it was all right; it would do him good. The flag was never to be lowered, and so we lived dangerously, from day to day, till the British authorities swooped on us one day. turned us out, and put the offices under lock and key.

There can be no end to reminiscences; I can here only recall a few illustrations of Jawaharlal Nehru's respect for freedom of the press and his endless interest in its involved, impeded operation. I must exclude the fairly long and interesting story of the relations between him and at least one editor, who has been editing for eighteen years, overlapping the period of freedom, the paper, of which he was the leading founder and chairman till he became Prime Minister. Then he resigned from a non-profit-making company, only, as he told Lord Wavell, for the sake of propriety and not from legal obligation, and, as he told me, not to embarrass me or be embarrassed by me, I welcomed this greater freedom. I alone agreed with him and I must also tell some other time how he defended my freedom, how he nursed and cherished it, and how he valued it.

I recall two instances only, in my 25 years of association with him, when he requested me to write on something. The first time was when at the AICC session of January, 1942, in Allahabad, he beckoned to me (an assistant editor then) from the press group, took me aside, and suggested to me that I should write an editorial asking the (British) Government to open diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. I wrote a short second leader on the subject. Later, meeting me in our office in Lucknow, he said he would like me to write a longer article on the subject. The second occasion was when, as Prime Minister, discussing the situation in Pakistan with me, he asked me earnestly to write an editorial article urging the release of the Frontier Gandhi. He was almost imploring me, and, by the way, he referred to the book, I had read, by Abdul Qaiyum Khan, by now notorious, on guns and gold on the Frontier.

This concern for editor's freedom extended beyond freedom of expression to relations with directors and managers. Nobody was to interfere with the editor's functioning; he might be right or wrong; but if his integrity was unquestioned, he was to function freely, once he was appointed. In the days when INA people were returning to this country as semi-heroes, Jawaharlal Nehru, yet to become Prime Minister, passed on some of them claiming to be journalists with recommendatory letters. Every letter was not only polite but cautiously worded; it was for the editor to decide. I rejected almost all of them; I took only one, and he did not stay long because of the terms I imposed on him. Jawaharlal Nehru told me later that I had done well to decide on my own responsibility.

Jawaharlal Nehru wanted all editors to have the freedom necessary to function freely, to develop character, and impress their character on the paper they edited. It was partly from this point of view that he disliked the new developments in the press, the passing of crucial centres of the press to a particular class from Marwar, the growth of chains, the degradation to which editorial staffs were reduced by proprietors, interested primarily in other industries, through managers, who were not fit to manage anything but factories. In address after address to the All-India Newspaper Editors' Conference, he spoke about the need for maintaining quality, in the midst of so much talk of the need for growth. He understood with greater clarity than proprietors and managers and editors the basic problems of the press. It was so, when after a week's aimless talk of largely imaginary circulations and demand for newsprint at a press seminar last year in Delhi, he blew a strong breath of realism into the discussions, when in his valedictory address, he said he did not believe in growth merely for the sake of growth. He insisted on quality, on a sense of social responsibility in the press, and on diffusion of ownership.

Interest in Practical Problems

After the fierce debates, mainly between press lords and the Home Minister, on the amendments to article 19 of the Constitution in 1951, Jawaharlal Nehru started taking a practical interest in problems of the press. There was talk of an inquiry into what was the basis of freedom of the press, whose freedom it was, and how that freedom was exercised, and whenever I saw him in those days, mainly in his house, I saw on his table a copy of the report of the Royal Commission on the Press. He was studying it closely, and he took great interest in the appointment of the Indian Press Commission. No one but the Federation of Working Journalists wanted it. The commission's recommendations were clumsily and weakly handled by the Information Ministry, and there was little that Jawaharlal Nehru could do, without being urged by organised professional opinion. The Price-Page Schedule baffled every one. I tried to explain to him. "It seems complex," he said. Then he conceded, "It seems simple too." The cabinet approved it, but the ministry wasted time in juggling with it, and then the Supreme Court squashed it. The Price-Page Schedule, which raises great passions among press interests, is dead, but the press will hear of it again.

[Nehru’s] concern for editor’s freedom extended beyond freedom of expression to relations with directors and managers. Nobody was to interfere with the editor’s functioning; he might be right or wrong; but if his integrity was unquestioned, he was to function freely, once he was appointed.

What are chains, groups, multiple units, or single newspapers for? Jawaharlal Nehru did not like chains; he did not like press barons or any other barons; he did not like editors who served only baronial interests. He wanted newspapers to be equal to their responsibilities; it means free operation, absence of restrictive and unfair practices, and a high degree of editorial ability and integrity. He demanded standards. In this, he had his own preferences. He did not like too many headlines in a page, for instance; no intelligent mind does. The Hindi press was a disappointment to him, especially its preference for Sanskritised diction, which did not appeal to the people and was not even intelligible. "The Hindi press needs a Northcliffe to start with," he told me more than once, not that he admired Northcliffe's methods but that he admired Northcliffe's insight into the mind of the reader. There was nothing that, he did not know of the leading newspapers and journalists of the world; in his "autobiography", he writes at length of the Indian press of those days, deploring its deploring its staidness, spinsterliness, and lack of touch with the people.

Jawaharlal Nehru was looking forward to mass circulations, and he knew of the vast untapped potentialities of readership. Still, he would not allow any pandering to the mass mind. If standards had to be maintained, he looked to working journalists. I found it easy to enlist his sympathy in their cause; he did not like too high salaries for the favoured and the fortunate, who at the top pretended to be big journalists because of their salaries or pompous courtship; he wanted the lower echelons to be brought up. But he was disappointed with working journalists and their organisation too. "I have read the report of your speech and of your resolutions, but what effective steps are you taking to raise standards?" he asked me, even after the convention, in 1950, with which we started our crusade. I could tell him nothing except that our first objective was the raising and maintenance of standards and the improvement in emoluments and working conditions was only our second objective; in any case, I was an editor who could be responsible for standards but most of the rest were only working journalists and standards depended on proprietors and editors. I was not convincing even to myself. Our record has been poor. I could not do much to infect my fellow working journalists with zeal for professional standards; my successors have done nothing.

Jawaharlal Nehru did not like chains; he did not like press barons or any other barons; he did not like editors who served only baronial interests.

Jawaharlal Nehru was not vague about the press set-up. He kept himself informed of changing ownership; he discussed changes in policy; he would ask what was behind the change in policy in one paper or another; he had something to say about this editor or that. At press conferences, he knew only faces and did not know names, but in the free-for-all exchanges, in which some press correspondents did not fail to insult him, he knew who was behind a question and who was behind the questioner. He liked the press conferences; they made the press correspondents tense and some of them felt important, though they gave more information than they sought: he relaxed. At a similar press conference once in Brioni, I saw him confound a host of foreign pressmen by declaring he was a pagan. They could not understand him, but he understood himself.

Jawaharlal Nehru did not like the Press Emergency Powers Act; he did not want the Defence of India Rules to be strictly enforced against the press. But he deplored misuse of freedom, sometimes strongly. If it came to a question of action, he preferred self-regulation. He was probably asking professional organisations to do much more than they could, but that showed the respect he tried to maintain towards the press, like the respect he always maintained for Parliament.

With Jawaharlal Nehru is gone a passionate defender of press freedom, as of all freedom. He stood for tolerance; there may be more increasingly less and less tolerance from authority, though the press is now trying to swear conformity With a set-up the mediocrity of which it finds comforting. He stood for values; these values may suffer gradually. He stood for decencies; these decencies may diminish. He distrusted monopoly; monopolistic tendencies may multiply. The testing period may not be far off. Whether he did anything or not, his presence was a rebuke to ugly tendencies. With lesser men, liberties have to be constantly guarded. When there is so much talk of the heritage of Jawaharlal Nehru, there will have to be equal interest in the heritage of values he left for the press.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 12 Nov 2016, 2:13 AM