The Qawwali Photo Project: Finding faces and stories hidden behind our beloved music

With over 400 qawwals associated with her and three photographers by her side, Manjari Chaturvedi managed to curate pictures from Awadh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Delhi, and Hyderabad

Manjari Chaturvedi, founder of the Sufi Kathak Foundation, remembers asking Qawwals (musicians who perform the Qawwali art form) across India about their traditions, their forefathers and their Qawwali lineage. She heard great stories and legends about them, but on asking for pictures, realised the music form had never been photographically documented.

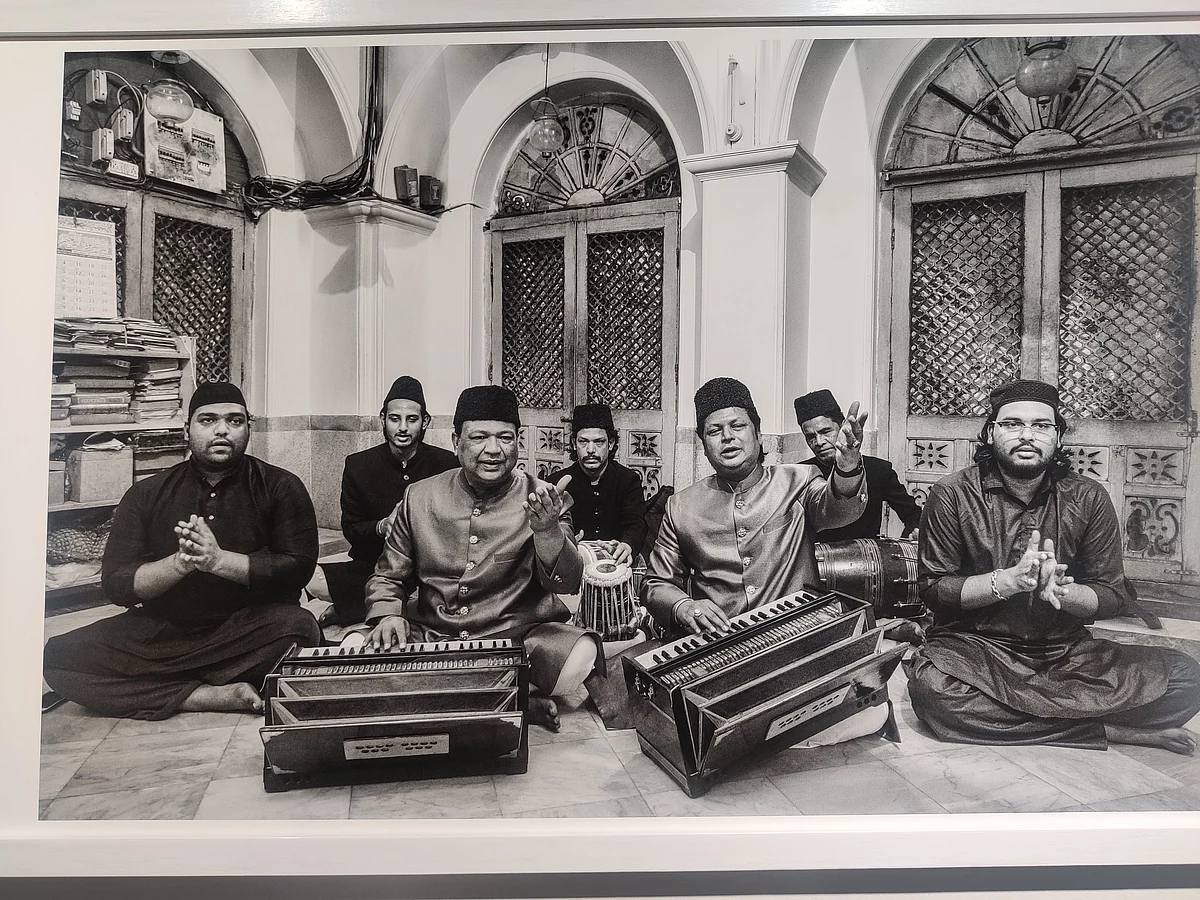

Chaturvedi laments that all there’s left of a lot of great Qawwals is nothing but a few passport size photographs. Chaturvedi’s recently concluded exhibition at the Museo Camera Centre for the Photographic Arts in Gurgaon, that ran from April-May 2022, titled “The Qawwali Photo Project ~ An Untold Story” was an attempt to change that. With over 400 qawwals associated with her and three photographers by her side, Chaturvedi managed to curate pictures from Awadh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Delhi, and Hyderabad.

From the Qawwali performed on the occasion of Sufi Basant at the Nizamuddin Dargah in New Delhi, to the songs sung at Dewa Sharif, Ajmer Sharif, and Fatehpur Sikri, to women practicing and performing across dargahs, the exhibition gave a deep dive into the music form revered by so many.

The Qawwali Project, interestingly, started nearly a decade ago, because Chaturvedi felt that there was so much organic knowledge, so many stories passed down from generation to generation through verbal tales that needed to be recorded.

But she also felt that there was a callous attitude that most people had towards Qawwals. Says she, “It was such that yes these Qawwals sing at dargahs and people go and listen for a few minutes and then throw money in front of them and leave. That’s what the entire relation of the audience with Qawwals and Qawwali was reduced to.” She sighs, before adding, “Except for when people would want to vibe to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music in a ‘Sufi mood’”.

What irks Chaturvedi the most is how this art form hasn’t been documented despite having the technology to do so. She also understands that not everyone has to be as passionate about Qawwali as she is, but she wanted to document Qawwalis inside the dargahs, “in that moment, in that energy”.

There’s no sense of respect or the urge to support these artists, rues Chaturvedi. Having supported a lot of Qawwal families, monetarily and otherwise, during the past two years, Chaturvedi saw how the pandemic bent them out of shape, leaving them behind with broken morale, wondering when they’ll sing again.

However, to her delight, photographers Dinesh Khanna, Mustafa Quraishi, and Leena Kejriwal joined Chaturvedi’s bandwagon. Khanna started by capturing Meraj Ahmed Nizami Qawwal, who was the senior-most Qawwal in Delhi at age 92. Grins Chaturvedi, “Dinesh travelled extensively and got sucked into the world of this beautiful art form.”

Chaturvedi points out that on seeing her exhibition, a lot of people were surprised that Qawwali existed outside of Awadh, Delhi, and Ajmer. She explains, “The same music form was adapted differently in different places with the local dialect and local language. We wanted to keep that intact, to show the places the Qawwals belonged to.”

A small segment of the exhibition, “I am a Qawwal”, featured pictures, names, and hometowns of the musicians who the photographers haven’t been able to document during their performances. Still, the Qawwali aficionado in Chaturvedi is happy, “there’s at least something we have to cherish for posterity, for history.”

Many unknown aspects of Qawwali were given a corner in this exhibition. One of them is women Qawwals. Just like Birju Maharaj’s daughters were not allowed to take up Kathak professionally and perform on stage until very recently, Qawwali too is an androcentric tradition, passed from men to men. Not only was the art form’s setup patriarchal, but there also was policing under religious tenets, which didn’t give women permission to sing in front of men.

But the women resisted. Chaturvedi beams with pride as she says, “Even if people do not consider women singing Qawwalis as legitimate, when they have been doing this for the past 25 years or so, they are very much a part of the tradition.”

Another lesser-known aspect was how Qawwals used their music as a form of resistance against tyranny. Chaturvedi underlines how Qawwals sang songs of resistance against the Britishers. She adds that there’s no mention of it in history or books, but something that the Qawwals have told her verbally. Even in Pakistan, it was used to voice dissent, she adds. But more recently, Qawwali was performed at the anti-CAA movement at Shaheen Bagh. All the more worthy to be highlighted because it was performed by Qawwal Sarvjeet Tamta, brushing away the notion that Qawwali is just an Islamic tradition.

The only change that Chaturvedi aims and hopes to bring with her project is not letting people forget the faces and stories that often get lost behind the music playing from our streaming services.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines