The fake history juggernaut trundles on

In a dramatic departure from its earlier edition, NCERT's newly released Class 7 social science textbook resorts to politically motivated retelling of the ‘Ghaznavid Invasions’

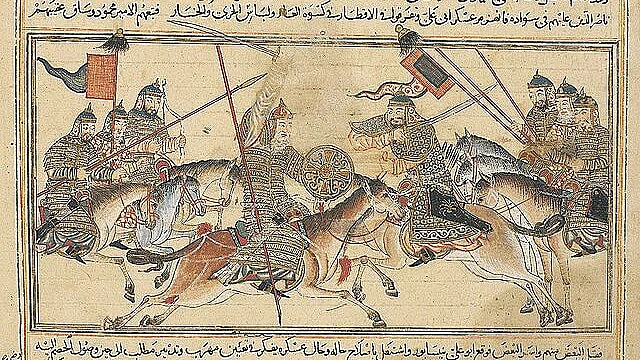

The BJP-Sangh project to rewrite medieval Indian history has turned NCERT textbooks into an ideological battlefield. The most recent focus of this bigoted enterprise is the ‘Ghaznavid Invasions’, most famously under Mahmud of Ghazni. And its chosen first victim the newly released Class 7 NCERT social science textbook, titled Exploring Society, India and Beyond.

Introduced with a cautionary preface on history’s ‘darker periods’, the book expands its treatment of said invasions, casting Mahmud of Ghazni foremost as a religious zealot. Mahmud, in this characterisation, is seen as a ruthless iconoclast determined to ‘spread his version of Islam to non-Muslim parts of the world’. The retelling relies on court chroniclers like Al-Utbi and Al-Biruni to underline Mahmud’s alleged obsession with slaughtering ‘infidels’ and storming temples—especially Somnath.

This is a dramatic departure from the earlier NCERT (National Council of Educational Research and Training) edition, which covered Mahmud of Ghazni in a brief paragraph (remember this is a Class 7 textbook), noting that his 17 opportunistic raids in the subcontinent were primarily aimed at looting the wealth of these temples.

Confronting uncomfortable histories is a legitimate pedagogical aim. But this project is not pedagogical; it’s political—and the aim, once again, is to reduce the complexity of underlying motivations to a Hindu–Muslim binary that serious historiography has long rejected. Eminent scholars like Mohammad Habib, Satish Chandra and Romila Thapar have repeatedly demonstrated that Mahmud’s incursions were driven less by religious piety than by the fiscal imperatives of sustaining a volatile Central Asian empire.

While making all these new additions and foregrounding a different set of motivations for the raids, what the textbook fails to register is that the plundering of temples and their ‘desecration’ was not always religiously motivated, and the practice long predated the arrival of Turks from Central Asia.

In early medieval India, temples were not merely religious centres but repositories of royal wealth, land grants and markers of political legitimacy—making them prime targets in inter-dynastic warfare. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini records that Harsha of Kashmir (11th century) systematically destroyed temples and melted their images to replenish the royal treasury.

Also Read: A dark chapter in the history of NCERT

Harsha, a Hindu ruler, appointed a special officer, the ‘Devotpatana Nayaka’ (literally: leader/ officer for uprooting/ destroying deities), not out of religious zealotry but for political consolidation and wealth extraction in times of fiscal stress.

A similar logic operated in peninsular India. The celebrated Rajendra Chola I, whose naval expeditions reached Bengal and Southeast Asia in the 11th century, carried off immense wealth—including temple treasures—from defeated kingdoms. Inscriptions proudly record the seizure of sacred icons and ritual wealth as symbols of imperial triumph.

Cutting across swathes of early and medieval India—from the Rashtrakutas to the Chalukyas—rulers attacked rival shrines because temples embodied sovereignty, not because the faith of the raiders demanded iconoclasm. These facts underscore a pattern: sacred places of worship were repeatedly violated by rulers to assert their domination and to extract wealth.

To recognise this pattern and to accommodate this complexity does not absolve Mahmud of Ghazni of the violence; it places his incursions in the correct historical perspective, and corrects the misconception that the political culture of plunder was somehow a uniquely Islamic perversion.

In its dramatic retelling of Mahmud’s 17 campaigns between 1001 and 1027 CE, culminating in the sack of Somnath, the textbook privileges Al-Utbi’s triumphalist account of temple destruction and Al-Biruni’s report of the shattered Shivalinga being transported to Ghazni. Truth is these accounts were directed at a courtly audience and have flourishes that characteristically exaggerate details for that audience.

As Romila Thapar argues in Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History (2004), the rhetoric of jihad in such chronicles was often hyperbolic and instrumental, deployed to enhance Mahmud’s standing with the Abbasid Caliphate and to legitimise his rule at home.

Drawing on Persian, Sanskrit and Jain sources, Thapar demonstrates that temples were attacked not as religious targets but as symbols of political authority and concentrated wealth. Somnath represented Chalukya sovereignty as much as Shaivite devotion. Its destruction was a calculated geopolitical strike rather than a civilisational war.

Thapar further notes that contemporary Indian responses to Somnath were notably muted; the idea of a cataclysmic Hindu–Muslim rupture emerged much later, shaped by colonial historiography eager to frame Indian history as an unbroken saga of religious conflict.

Mohammad Habib’s Sultan Mahmud of Ghaznin (1951) remains decisive in rejecting the caricature of Mahmud as a religious fanatic. Habib argues that Islam sanctions neither indiscriminate plunder nor vandalism, and that Mahmud lacked the doctrinal zeal associated with later rulers. His overriding concern was funding his army, appeasing Turkic chiefs, and defending his empire against Central Asian rivals. Habib’s meticulous accounting of loot—from Nagarkot to Kannauj—demonstrates how Indian wealth underwrote Ghazni’s monuments and military power. Numismatic evidence further confirms the circulation of Indian gold in Ghaznavid mints.

Satish Chandra, in Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, offers a balanced synthesis. Mahmud’s raids combined plunder with political spectacle, but economics remained paramount. Unlike Muhammad Ghori, Mahmud neither sought nor established durable rule in India. His expeditions were calculated strikes into a politically fragmented landscape where temples—like forts and treasuries—offered accessible resources.

Together, these scholarly interventions expose the dangers of NCERT’s selective reliance on Al-Utbi and Al-Biruni. Utbi exaggerated casualty figures to glorify his patron; Biruni, despite his admiration for Indian learning, wrote under Ghaznavid patronage. Missing from the textbook are countervailing voices such as the Ekalinga Mahatmya, also known as Ekalinga Purana, which laments Somnath’s fall in economic rather than metaphysical terms. By framing Mahmud primarily as a proselytising butcher, the NCERT echoes colonial tropes that Romila Thapar identifies as ‘communal dogma’.

Earlier NCERT textbooks explicitly noted that temples were targeted because rulers endowed them as markers of sovereignty. To deliberately distort this history in middle school textbooks is to plant a bigoted worldview in young minds. It obscures the reality that Indian polities—from the Cholas to the Rashtrakutas—had a shared political grammar, where wealth extraction—not religious conversion—was the primary motive driving warfare.

In this politically motivated reconstruction of history, students will learn to view the medieval past as a perpetual clash of faiths rather than a contest between political economies. Across centuries, rulers have couched resource extraction in the moralising idiom of divine sanction, civilisational duty, national security and suchlike. But that shouldn’t obscure our understanding of what really happened and why.

Teaching history is neither about sanitising violence nor about weaponising memory for political ends. It is about cultivating critical engagement with sources, context, complexity. A balanced pedagogy introduces multiplicity, encourages scepticism of triumphalist narratives, and situates events in broader political and economic frameworks. Such an approach equips students not with inherited resentments, but with historical literacy—the most enduring gift a history curriculum can offer.

HASNAIN NAQVI is a former member of the history faculty of St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai

Also Read: The Kafkaesque world of the NCERT

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines