Why India’s rejection of global AQ benchmarks may be dangerous

India’s rejection of global AQ benchmarks raises fears of weakened safeguards as pollution levels remain extreme

India’s rejection of international air-quality rankings and distancing from the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) guidelines has drawn fresh concern from environmental and public-health experts. Analysts warn that sidelining widely referenced benchmarks may weaken efforts to protect citizens from some of the worst pollution levels on the planet.

On Thursday in the Rajya Sabha, minister of state for environment Kirti Vardhan Singh told MPs that global air-quality rankings “are not conducted by any official authority” and that WHO’s air-quality guidelines serve only as “advisory values, not binding standards”.

He emphasised that countries are free to set their own standards based on “geography, environmental conditions, background levels and national circumstances”, and noted that India already has its own National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) covering 12 pollutants.

Singh also pointed to the government’s annual Swachh Vayu Survekshan, which evaluates air-quality improvement efforts in 130 Indian cities under the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) and rewards progress on National Swachh Vayu Diwas each year.

While technically correct that WHO guidelines are not legally binding and that no global authority issues an “official ranking”, experts say the ministry’s framing risks obscuring a larger public-health crisis.

Global air-quality reports — such as the World Air Quality Report published by IQAir and other PM2.5 datasets used by researchers and health agencies — consistently show that the majority of the world’s most polluted cities by annual fine particulate matter (PM2.5) are in India.

In recent rankings, independent data placed around two-thirds or more of the top 30 most polluted cities in India, particularly in the northern states, a trend that analysts project into 2024 based on ongoing measurements.

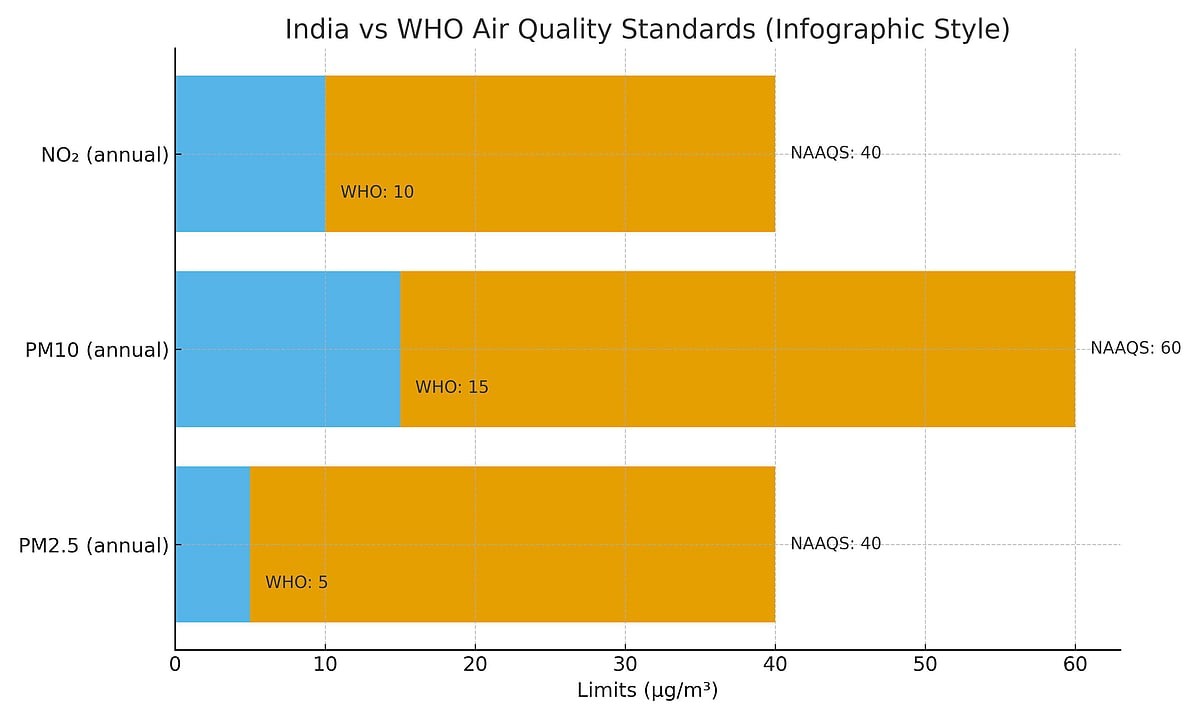

WHO air-quality guidelines are built on extensive epidemiological research linking PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide and ozone exposures with increased risks of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, stroke, low birth weight and premature death. By contrast, India’s NAAQS for several key pollutants — including an annual PM2.5 limit that is significantly higher than the WHO guideline — allow pollutant concentrations that scientists consider hazardous to health.

Public-health researchers argue that treating WHO values merely as advisory rather than as science-based thresholds to aspire to may underplay the severity of pollution exposure for millions of people. They also caution that dismissing well-used global indices as unofficial reduces transparency and undermines international comparability at a time when air pollution is one of India’s leading avoidable health risks.

Similarly, while the Survekshan rankings help track administrative improvements and policy implementation, they do not measure pollution in relation to health-protective exposure limits. A city can improve relative to its own past performance yet still remain far above levels shown by global science to be dangerous.

The broader hazard, experts say, lies in decoupling India’s air-quality planning from global scientific consensus at a moment when domestic measurements repeatedly place Indian cities at the top of annual PM2.5 charts. This not only affects how the crisis is communicated to the public but may influence how governments prioritise regulatory action.

For now, the government appears committed to its current framework. But health advocates warn that unless national standards draw closer to the strongest global evidence — rather than only asserting sovereign authority over benchmarks — millions of Indians will continue to breathe air that independent science describes as unsafe.

With PTI inputs

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines