Use computerised lottery to allocate cases in HCs and SC, appoint judges, urges law expert

Author and legal scholar Gautam Bhatia also suggests separate Supreme Courts for criminal, service, labour or taxation matters

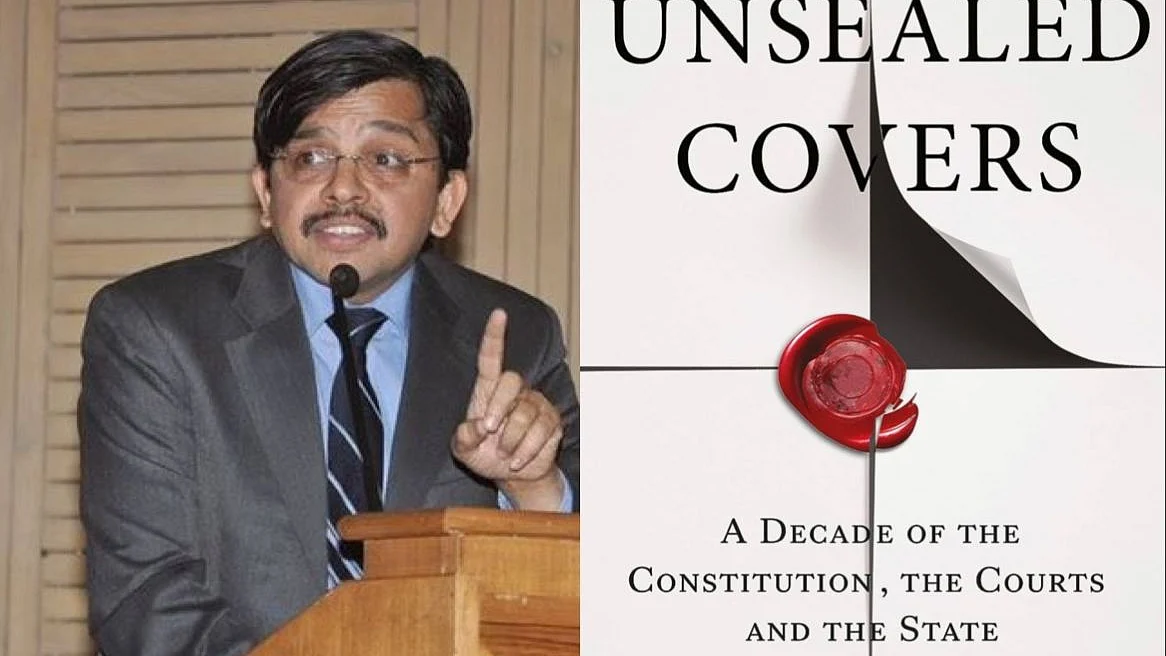

‘What we wear, what we eat, what we speak, where we worship’ are all becoming constitutional issues and judges are being forced to make a choice and pronounce judgment, agreed speakers at a panel discussion in New Delhi on Thursday to mark the launch of legal scholar, writer and advocate Gautam Bhatia’s new book, Unsealed Covers: A Decade of the Constitution, the Courts, and the State.

The discussion at New Delhi's India International Centre was moderated by senior editor Seema Chisti and included Justice S Muralidhar, former chief justice of Orissa High Court, whose elevation to the Supreme Court was stalled by the Modi government, and renowned criminal lawyer Rebecca John.

Personal and political prejudices of judges, the speakers agreed, are clouding judgments and judicial processes. While both Bhatia and John spoke of the compulsion among lawyers to look up the background of judges before formulating their arguments, John recalled in lighter vein that on a visit to a high court, she was advised to argue in Hindi because the judge was known to have denied relief to women lawyers, especially those who argued in English.

With 34 Supreme Court justices sitting in batches of two to hear cases, Bhatia argued, it was unfair to make the Chief Justice of India allocate cases to different benches. Moreover, the arbitrary power vested in the CJI to allocate cases to different benches as ‘master of the roster’ is what makes political parties and governments strive to place their own nominees as CJI.

A far better system of allocating cases, he suggested, could be by computerised and randomised lottery. Another solution could be to have separate Supreme Courts for criminal, service, labour or taxation matters, he suggested.

The way judges are appointed in India is also problematic, Bhatia felt. The resolutions of the collegium recommending appointment of judges to the high courts and the Supreme Court rarely provide any ideas about a nominee’s beliefs, biases and background, he pointed out. In practice, all judges do come with personal and political biases, but are forced to pretend that they are neutral and above all bias.

A far better system of appointing judges, Bhatia said, is what the Judicial Appointments Commission does in South Africa. The commission holds public hearings and conducts interviews in public before making its recommendations. Both press and public get access to them and get to know the judges and their biases if any.

During the interviews, the South African commission often asks shortlisted nominees to identify a constitutional court judgment that they disagree with; and then proceed to advance arguments they would make to overturn those judgments.

The US system of appointing judges is at least ‘honest’, Bhatia said, in the sense that the incumbent President and the party he or she represents fills vacancies in the Supreme Court with their own preferred judges. They are political appointees but people know what they stand for. In India, however, the system merely "pretends the judiciary and judicial processes are depoliticised", Bhatia quipped, "which is dishonest".

Justice Muralidhar agreed that at a time when “many issues coming to court are political issues dressed as legal issues”, judges are forced to make a choice in public. “They may think they are being neutral… (but) politics and judicial functioning are not as separate as we want them to be. They are getting increasingly mixed up,” he pointed out.

Bhatia cited the cases of demolition of houses following violence in different parts of the country. In almost all such cases, the ruling parties claim the demolitions as proof of ‘revenge’ or ‘good governance’ and municipalities produce notices to prove that it was all ‘encroachment’. With virtually 80 per cent of buildings in urban areas guilty of regulatory violations, courts have few options but to accept such submissions at face value.

It is not easy to be a judge, quipped Bhatia, but only systemic changes and reforms can make the judiciary more sensitive to the calls of justice and needs of citizens.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines