26 lakh Bengal voter names don’t match 2002 rolls: Election Commission

For unmatched names, document-based verification will confirm identity and eligibility, an official says

The Election Commission has drawn back the curtain on a striking revelation in West Bengal’s electoral landscape: nearly 26 lakh names in the state’s current voter rolls do not align with entries recorded in the voter lists of 2002. The finding, an official disclosed on Wednesday, emerged from a sweeping and painstaking comparison between the latest rolls and those compiled across multiple states during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) exercise conducted between 2002 and 2006.

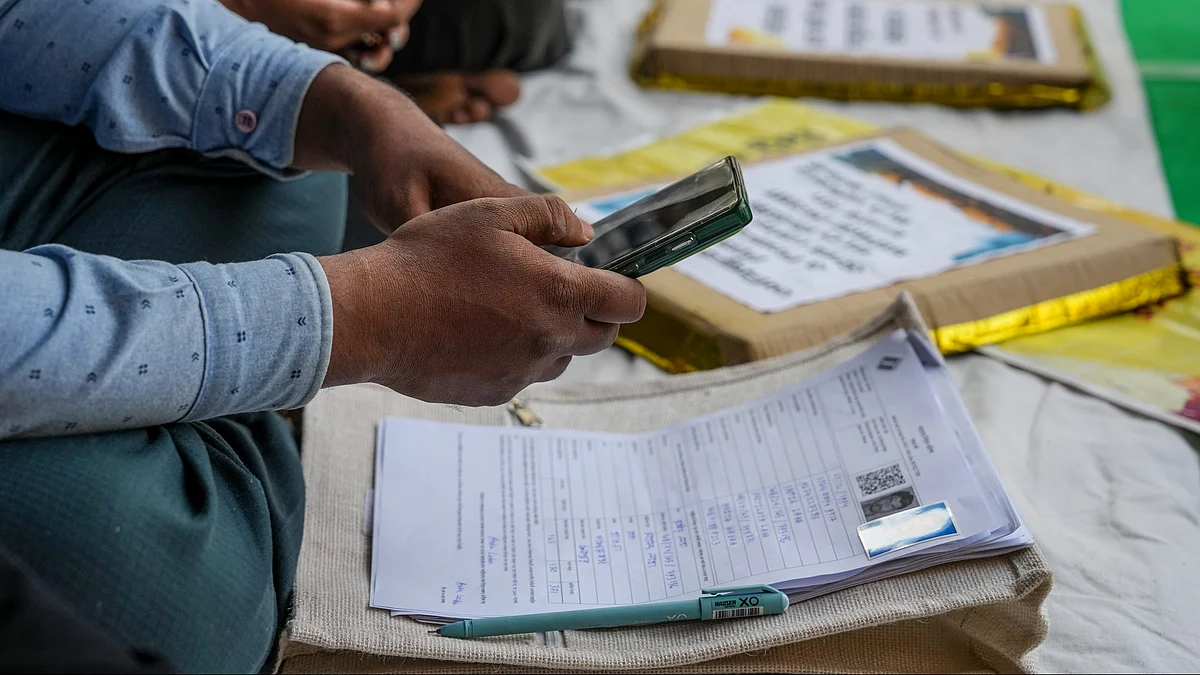

This revelation comes as the state races through an enormous digitisation effort. By Wednesday afternoon, more than six crore enumeration forms — each one a small but vital fragment of the democratic mosaic — had been converted into digital records under the ongoing SIR process.

“Once digitised, these forms undergo an elaborate mapping procedure,” the official explained to PTI. “They are matched against the SIR archives, and our initial analysis shows that around 26 lakh names could not yet be reconciled with earlier records.”

Behind this large number lies a story of mobility and demographic transformation. Many of the individuals whose names appeared in the earlier voter rolls of other states may have relocated to West Bengal over the past two decades. Such voters, the official emphasised, remain full citizens entitled to the franchise — regardless of which state once recorded their names. It was by cross-matching Bengal’s rolls with those of other states that the commission identified the large pool of currently unmatched names. And as digitisation continues at pace, the figure may grow.

Central to this massive verification undertaking is the concept of “mapping” — an exercise that resembles both forensic reconstruction and genealogical tracing. The process does not merely search for identical names; it identifies overlaps, detects familial linkages, and checks whether the parents of current voters were present in the 2002 SIR rolls. Whenever such patterns align, a voter is automatically authenticated without the need for separate documentation, making the system both rigorous and efficient.

This year’s mapping exercise is more ambitious than any before it. For the first time, voter lists from other states have been woven into the verification net, a move the chief electoral officer’s office believes will yield a truer, more comprehensive reflection of the state’s electorate — especially in an age of increasing migration.

Yet, officials were keen to dispel anxieties that such mismatches might translate into summary exclusions. “A name not matching the earlier records is not a verdict,” the official stressed. “It does not mean automatic deletion from the electoral rolls.”

Voters whose details match older listings will not need to furnish additional documents; they only need to fill the standard enumeration form. For those whose names cannot yet be traced across the archival data, a careful, document-based verification will follow to establish their identity and eligibility.

In its formal stance, the Election Commission has underscored that this vast, data-driven exercise seeks to strengthen the integrity of the democratic process. Ensuring accuracy and transparency, the commission reiterated, is paramount — and no eligible voter will be left behind without thorough, compassionate, and meticulous scrutiny.

With PTI inputs

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines