Nation

Birsa Munda: The enduring flame of tribal resistance and indigenous pride

More than a symbol of resistance, Birsa Munda remains a lodestar for indigenous identity, ecological justice, and communal dignity

Born on November 15, 1875, in Ulihatu in present-day Jharkhand, Birsa Munda grew up within the cultural world of the Mundas, an Adivasi community whose social fabric revolved around communal landholding, sacred groves, and a deep spiritual bond with nature.

His brief encounter with missionary schooling and Christianity ended in rejection, as he gravitated instead toward Vaishnav influences and his community’s indigenous belief systems.

The young reformer soon founded the Birsait movement, preaching monotheism through the deity Singhbonga and urging social renewal.

His teachings challenged alcoholism, witch-hunting, and exploitation while emphasising unity, sanitation, self-respect, and the moral authority of the tribe. Adivasis revered him as Dharti Aaba — Father of the Earth — a title reflecting both his spiritual charisma and his defence of land as a collective inheritance.

Ulgulan: When a reformer became a rebel

By the late nineteenth century, colonial policies had upended the traditional khuntkatti system that recognised communal ownership of land.

The imposition of zamindars, moneylenders, and forced labour regimes — coupled with cultural intrusion by missionary establishments — pushed the community to the brink. Birsa’s spiritual movement soon evolved into an organised political challenge to these structures.

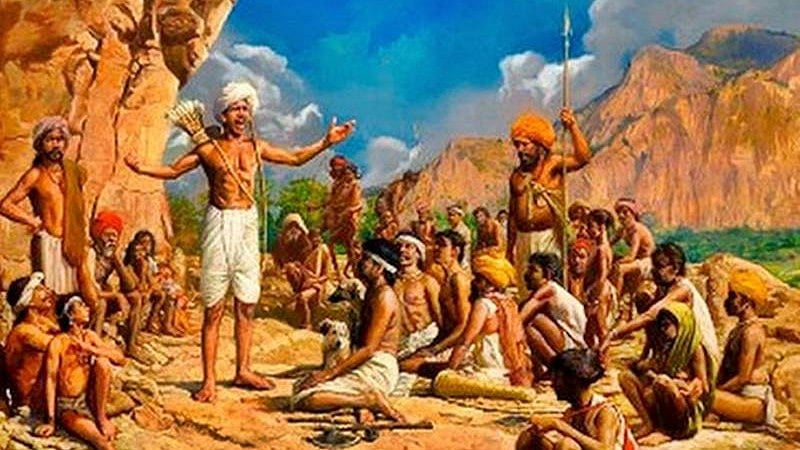

The Ulgulan, or Great Tumult, began as a cry for autonomy, encapsulated in his rallying call: “Abua raj setar jana, Maharani raj tundu jana” — let our self-rule return, let the Queen’s rule end. The movement blended cultural revival with political resistance, igniting hope across the Chotanagpur plateau. Though armed primarily with bows and arrows, his followers mounted bold attacks on police posts and symbols of colonial authority, utilising guerrilla tactics and the forested terrain to their advantage.

Birsa’s rising influence prompted swift repression. Arrested first in 1895 and jailed for two years, he resumed his mobilisation soon after release. His final arrest came during the crackdown that followed the uprising. On June 9, 1900, the 25-year-old leader died in Ranchi jail, officially of cholera. His passing ended the armed phase of the struggle but ignited a legacy that would outlast the Empire itself.

Published: undefined

Reform through sacrifice

The Ulgulan compelled the British to confront the scale of tribal dispossession. In 1908, the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act formalised protections for Adivasi land, prohibiting its transfer to outsiders and reaffirming khuntkatti rights.

Forced labour practices such as beth begari were curtailed. These reforms — though imperfect — acknowledged the injustices Birsa had raised and transformed the legal landscape for generations of Adivasis.

Independent India has increasingly embraced Birsa Munda as a national symbol of tribal valour and indigenous pride. Since 2021, November 15 has been observed as Janjatiya Gaurav Divas, marking his birth anniversary as a moment to celebrate Adivasi contributions to the nation.

The 150th year saw renewed attention to tribal histories through exhibitions, cultural programmes, and archival efforts reverberating across the country.His life has inspired a growing body of literature and popular works that bring tribal histories into the national imagination.

These narratives — whether scholarly biographies or children’s adaptations — have helped restore his place as a central figure in the story of India’s freedom and cultural diversity.

Legacy rooted in justice and ecological harmony

Birsa’s vision reaches far beyond the rebellion itself. His emphasis on collective welfare, ecological balance, and moral accountability carries deep relevance in an era marked by climate crises, resource conflicts, and displacement of indigenous communities.

Contemporary initiatives such as the Dharti Aaba Janjatiya Gram Utkarsh Abhiyan and the Pradhan Mantri Janjati Adivasi Nyaya Maha Abhiyan echo aspects of his philosophy by centring tribal development, empowerment, and dignity.

His life continues to resonate because it embodies a universal message: that justice cannot flourish where land and culture are stripped away; that communities thrive when rooted in identity, solidarity, and respect for nature; and that resistance powered by faith and collective purpose can shift the moral arc of history.

In remembering Birsa Munda, the country honours not only a revolutionary who confronted an empire but a visionary who offered an alternative imagination of dignity and development.

His flame endures — in forest movements, in struggles for land rights, in classrooms reclaiming forgotten pasts, and in every community that draws strength from its own cultural soil.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined