Nation

Natural disaster, manmade apathy: The unfair burden on non-BJP states

How Himachal Pradesh exemplifies the politicisation of aid and disaster relief

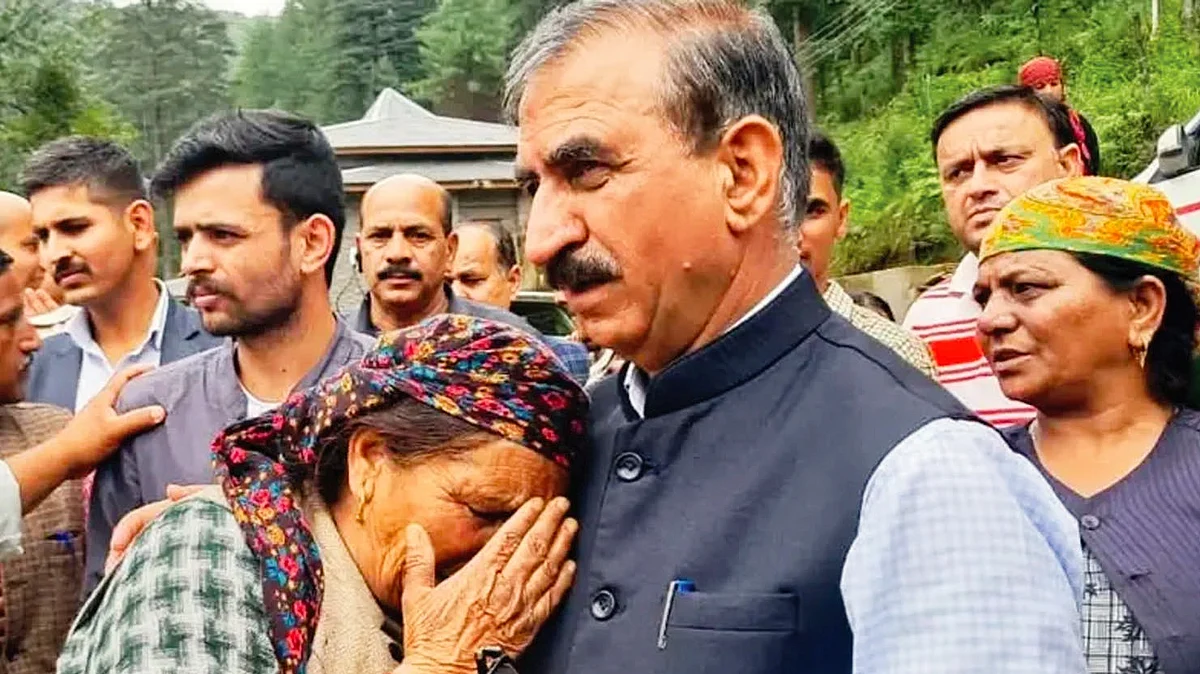

Himachal Pradesh chief minister Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu has witnessed one natural disaster after another, devastating parts of the hill state. Disappointed with the cold shoulder by New Delhi, he has gone about organising relief and rehabilitation with quiet self-assurance and stoicism. Over the years, he has learnt to make do with the state’s own scarce resources to rebuild lives and wrecked infrastructure. But the toll is mounting.

He was back in Delhi this week though, seeking emergency assistance from the Centre following flash floods and large-scale destruction after a series of cloudbursts in the Seraj Valley of Mandi district on 30 June. He called on finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, urging her to raise the state’s borrowing limit.

He also met Union home minister Amit Shah and apprised him of the extensive damage: destroyed roads, bridges and homes besides electrical transmission lines and other infrastructure. He even met Arvind Panagariya, chairman of the 16th Finance Commission, and proposed the creation of a dedicated ‘green fund’ to ensure timely aid for hill states during natural calamities.

Like chief ministers of other non-BJP-ruled states, Sukhu is by now used to receiving cordial, sometimes even warm, hospitality but little else. Demands for special assistance are invariably dragged for much longer compared to BJP-ruled states. When the purse strings are eventually loosened by New Delhi, the grants and aid are just that wee bit more generous. Disaster relief assistance from the Central government is not always driven purely by humanitarian concerns; political considerations too are never too far away and often play a significant role.

Published: undefined

In 2023, Joshimath in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district faced a severe crisis. Cracks began appearing on the land and residential buildings, followed by extensive damage to roads and streets. In some areas, the situation became so critical that residents had to be evacuated from their homes. Relocating such a large population was a daunting challenge, and alongside rehabilitation, the state planned structural repairs to damaged houses.

To manage the crisis, Uttarakhand initially sought Rs 2,943 crore as assistance from the Centre. Later, chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami personally appealed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, raising the request to Rs 3,500 crore.

Just as Himachal Pradesh’s demand for relief was kept under consideration for long, so was Uttarakhand’s. When the Centre finally announced its relief packages, it sanctioned Rs 1,658 crore for the Joshimath crisis — about 56 per cent of the requested amount. In contrast, Himachal Pradesh, which had sought Rs 9,042 crore for its far more widespread and deadly disaster, received only Rs 2,006 crore — just 22 per cent of what it had asked for.

This disparity raises an uncomfortable question: does the Central government respond differently based on which party is in power in a state? The numbers seem to suggest so.

It is true that no two natural disasters are the same. The scale of destruction, geographical conditions, population affected and long-term impact vary widely. Yet, what remains consistent — and troubling — is how politics seems to influence the nature and extent of the Central government’s response.

Published: undefined

When a disaster strikes a BJP-ruled state, the wheels of Central support appear to move faster, and the relief packages seem more generous. In contrast, when a non-BJP-ruled state like Himachal Pradesh is hit, the response often feels delayed, diluted or inadequate. This pattern raises serious questions about the impartiality of the Centre’s approach to disaster relief — an area that should be governed by urgency, empathy and equity, not political allegiance.

Today, as it grapples with yet another devastating natural calamity, Himachal Pradesh finds itself in a familiar position — seeking urgent aid, but bracing for minimal support. Based on past experience, it would be unrealistic for the state to expect full and timely assistance from the Centre. Despite the appeals, the figures and the humanitarian crisis on the ground, the Central treasury does not view every state through the same lens.

Disasters may be natural, but the relief that follows is often anything but. In India, the tragedy of the terrain is too often compounded by the tragedy of political bias.

Himachal Pradesh has incurred losses of Rs 21,000 crore in the last three years due to natural disasters. To put this in perspective, the state’s total annual budget is below Rs 58,500 crore, highlighting the urgent need for external support. With several Central schemes including highways cutting through the hills blamed for landslides and Union government’s policies to expand hydroelectric projects and ‘development’ at least partly responsible for the disasters, New Delhi can hardly shrug away its responsibility.

Published: undefined

The most recent blow came from a series of cloudbursts in Mandi district in late June, triggering flash floods and widespread devastation in Seraj Valley and nearby areas. Around 100 people lost their lives and many are still missing. The floods damaged or blocked 248 roads in Mandi district alone, brought down several bridges and destroyed 994 power transformers. Drinking water supply was completely disrupted.

Immediate cash relief of a paltry Rs 5,000 each and the state government pledging Rs 7 lakh to rebuild each home is deemed to be inadequate, fuelling discontent. Any delay in the sanction of Central assistance, and the longer it takes to reconstruct the damaged infrastructure, add to the discontent, indirectly serving a political interest. It also strains the state’s already stretched financial resources.

Past experience with New Delhi, however, is far from reassuring. In 2023, Himachal Pradesh was struck by the worst natural calamity in the region in 75 years. Cloudbursts, floods, and landslides during the monsoon caused widespread destruction. Over 550 people lost their lives, and more than 12,000 homes were either destroyed or severely damaged. Even national highways suffered extensive damage.

At the time, experts estimated the total loss at over Rs 12,000 crore. The state government formally requested for Rs 9,042 crore from the Centre to rebuild the affected areas and revive the local economy. Detailed proposals were submitted, outlining specific needs and funding requirements.

Published: undefined

Yet, months later, on 12 December 2023, the Centre approved Rs 633.73 crore as aid from the National Disaster Response Fund. By then, however, this amount had become largely symbolic — the state had already spent more than that on disaster relief.

The government was forced to divert Rs 4,493 crore from its own budget to manage relief and rehabilitation. For a hillstate with limited resources, this was an enormous burden and the impact on the state’s fragile finances was immediate and visible.

At the start of this year, the government struggled to pay salaries on time — monthly wages for state employees, typically disbursed on the 1st, were delayed till the 5th. Pension payments to retirees were pushed back even further.

Despite sustained efforts to stabilise the situation, financial pressure on the state continued to build. Chief minister Sukhu even met Prime Minister Narendra Modi to seek further assistance. Eventually, in mid-June, the Union home ministry announced an additional Rs 2,006 crore to aid Himachal’s recovery from the 2023 disaster.

In the end, after nearly two years of appeals and follow-ups, the state has received only 22 per cent of what it had requested from the Centre — a huge gap between need and support.

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined