Opinion

The rise of Zohran Mamdani and what it means for the Hindutva project

Mamdani’s open and eloquent rejection of Modi’s divisive politics can easily become a template for Indian-origin leaders abroad

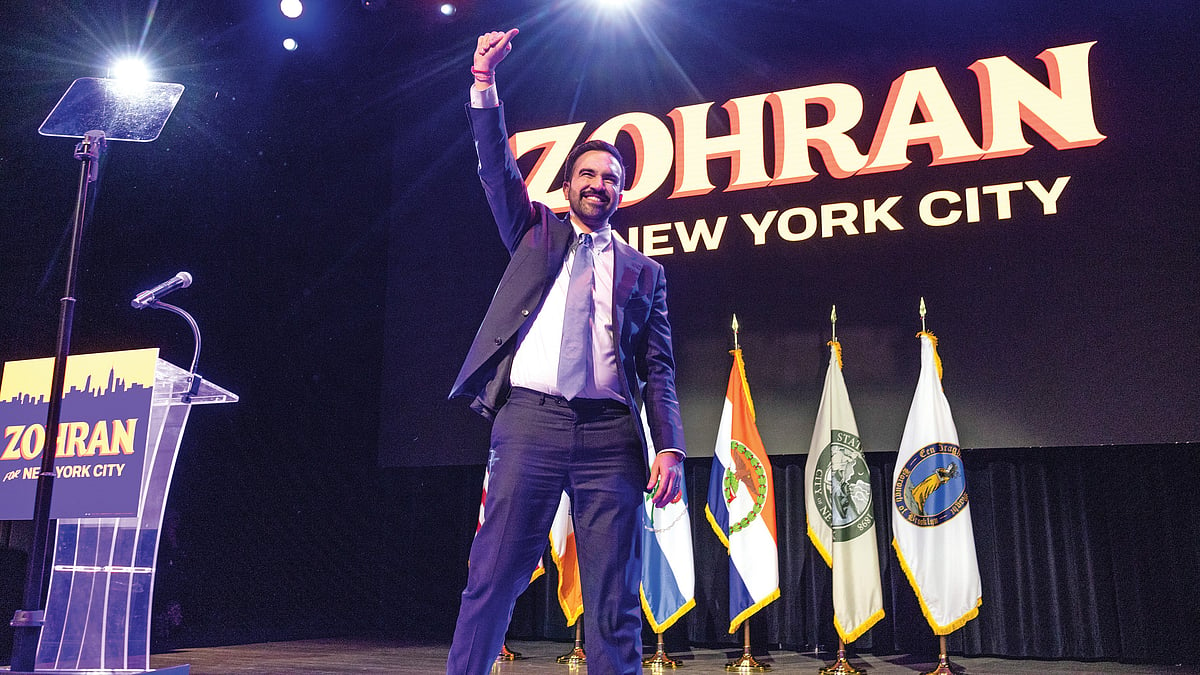

The election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York City is undeniably historic. His ascent signals big shifts in identity politics, diaspora mobilisation and progressive global linkages. His success has ripple effects, and Indians, whether they are aligned with his vision or opposed to it, know this. For the Modi regime, Mamdani’s rise is a strategic headache.

That a high-visibility American leader of Indian descent, with global reach, openly criticises Modi, invokes India’s pluralist past and identifies with an inclusive vision of citizenship means the Hindutva project is now facing a new kind of adversary: one whose notes of dissent will echo not just in New York but among diaspora communities, global progressive networks and India-outward foreign policy discourses.

Mamdani’s platform blends socialist economic ideals — rent freezes, expanded public housing and an aggressive affordability agenda — with a proud and visible embrace of his Indian heritage. In his victory speech, he invoked Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of an inclusive India and closed with the Bollywood song Dhoom Machale, symbolically merging his political idealism with cultural pride.

Throughout his campaign, Mamdani frequently spoke about his Indian roots and drew a contrast between the pluralist India he grew up hearing about and the exclusionary one represented by Modi’s BJP, “an India that only has room for certain kinds of Indians”, as he put it. He has publicly described Modi as a “war criminal”, linking his condemnation to the 2002 Gujarat riots and what he calls a broader pattern of political mobilisation through communal division.

From the perspective of the Hindutva camp, this matters at three levels.

Published: undefined

First, Mamdani offers a counter-narrative to the aggressively advertised image of Modi in India as the globally celebrated ‘strong leader’ with broad diaspora appeal. For years, the BJP government has sought to project India as a globally resurgent nation under Modi, a confident India that Indian-origin leaders abroad can embrace. But Mamdani challenges that script. His open and eloquent rejection of Modi’s divisive politics can easily become another template for Indian-origin leaders abroad, and Indian diplomats will likely have to grapple with this in days to come.

Second, Mamdani’s brand of politics reinforces the notion that Hindutva’s reach is not confined to India’s borders. The Hindu-nationalist project has increasingly been embedded in global networks of political mobilisation, diaspora advocacy, transnational organisations and international media. Mamdani’s election creates a mirror image: a Western politician of Indian origin who challenges the Hindutva narrative from outside, lending a fillip to opposition at home.

This is hardly a benign phenomenon for the BJP or its affiliated groups: as the diaspora becomes more assertive, the potential for external pressure and transnational activist linkages against Hindutva will rise. Since Mamdani brings global visibility, a progressive profile and access to American political infrastructure, he becomes a symbol of global support for those who oppose Hindutva inside India. That makes his ascent more than symbolic — it converts diaspora dissent into a credible international voice.

Third, the optics and practical implications matter for India–US relations and for bilateral diplomacy. The Modi government has long positioned itself as a reliable partner to the US, emphasising strategic alignment, economic partnership and a ‘diaspora bridge’ that cements India’s status as a global stakeholder.

Meanwhile, the US has refrained from strong public criticism of India’s internal politics in pursuit of strategic goals. But a figure like Mamdani complicates that calculus: his prominence means India cannot assume that Indian American voices will uniformly endorse its policies or that the diaspora will by default tilt in favour of New Delhi’s narratives.

Published: undefined

In other words, the Modi regime’s diaspora strategy now faces a counter-current in which an Indian-origin leader in the US might engage with India not just in terms of strategic convenience or economic partnership but also India’s outlook on pluralist values and human rights.

It is, therefore, misguided to think of Mamdani’s rise as an isolated event, for his success will empower diaspora communities critical of Modi, giving them a champion in high office and feeding their sense that criticism of India is not disloyalty. It will also signal to Western elites and media that the Indian government’s narrative will now face challenge even from its global diaspora.

Hindutva groups assessing the fallout have an awkward choice: to engage or to ignore. They could try to ignore Mamdani, but the more he uses his platform to speak about India, the more Indian politics will become embedded in diaspora debates. They could attack, but doing so risks producing a backlash that Modi would prefer to avoid. They could try to engage, which would force the regime to open up spaces for critique and opposition at home and abroad.

All this is not to suggest that Mamdani is about to trigger the collapse of the Hindutva project or that his new stature will immediately produce a big shift in Indian politics. But Mamdani’s rise certainly changes the battlefield. India’s political trajectory will now feature more prominently in global diaspora discussions, in Western city halls and progressive networks.

Mamdani’s ascent is bad news for Modi and the Hindutva crowd because it erodes their ability to monopolise the narrative of Indian-origin success in the West; it undercuts the assumption that diaspora leaders will align with their project, and it produces new vectors of critique that can connect the Opposition in India with pressure and support abroad.

Ashok Swain is a professor of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University, Sweden. More of his writing may be read here

Published: undefined

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: undefined