Ravana's different faces in MP — from son-in-law to protector, Brahmin king

As Dussehra nears and the rest of India readies to burn Ravana's effigy, some folks in Madhya Pradesh are telling a different tale

For centuries, across most of India, Ravana was portrayed as the ultimate villain — a 10-headed demon king whose defeat at the hands of Lord Rama symbolised the triumph of good over evil. Yet, in Madhya Pradesh, the story of Ravana was being told differently.

For some, he is a a revered son-in-law. For Brahmins of Ujjain, he is the devotee of Lord Shiva, who should be worshipped instead of his effigy being burned in public. And for the Gond tribespeople of Mahakaushal region, he is a protector.

In the village of Khanpura, around 350 km from state capital Bhopal, Ravana is not a villain to be burned, but a son-in-law to be revered, his 51-foot statue at the centre of the village a testament to the village’s devotion. Over decades, the statue has been weathered by time, yet stands tall and proud, say locals.

For the village's Namdev Vaishnav community, Ravana is family — husband of their daughter Mandodari, and a man of profound wisdom. On Dussehra, instead of being reduced to ashes, Ravana is celebrated. Women cover their heads as they pass by the statue paying their respects, while children tie red threads around its legs to ward off illness.

“We worship him for his wisdom and his devotion to Lord Shiva,” explains Ashok Bagherwal, president of the Namdev Vaishnav community. “For us, Ravana is not a demon but a revered scholar and protector of the family.”

Amid echoes of 'Ravan amar rahe (long live Ravana)', the village dances to dhols and traditional band performances, and the community offers him laddu and dal bafla — a traditional dish of the region.

But in Khanpura, the rituals surrounding Ravana’s worship are also about preserving an ancient cultural heritage. Elders in the village pass down stories of Ravana’s connection to Mandodari, weaving a fabric of pride and respect around him.

Almost 200 km from Mandsaur, in Ujjain, the Brahmin community has been campaigning to prohibit the public burning of Ravana's idol as he was a Brahmin and a great devotee of Shiva.

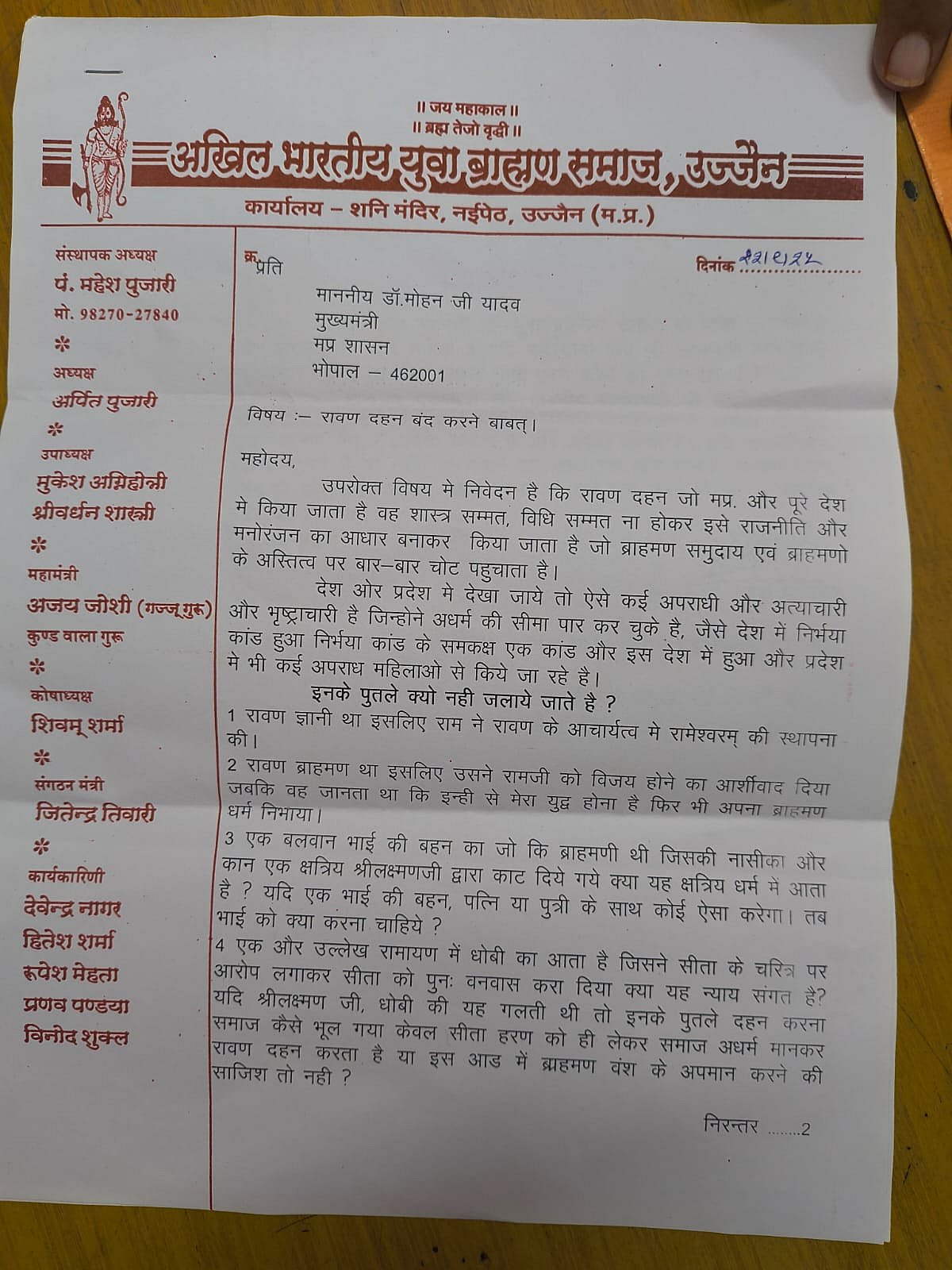

In a letter to the chief minister and prime minister on 22 September, the Akhil Bharatiya Yuva Brahman Samaj, Ujjain, argued, "Ravana’s penance was Brahminical. His family was revered. When Laxman attacked his sister Surpnakaha and humiliated her, as a brother, what should one do?"

The letter also asks, “There are many criminals and oppressors who have committed more crimes than Ravana. But we don’t burn their effigies. Then why should we, as a society, continue to dramatise the public murder of a Brahmin year after year?"

It also argues, “Sita was sent to vanvas (forest exile) after a launderer (dhobi) questioned her character, but she came out clean. Why weren't that washerman and Laxman’s effigy burned? Just because Ravana kidnapped Sita, he was termed a demon king?”

The Brahmin outfit pointed to Ravana’s ancestry: grandson of the great sage Pulastya, son of Vishwasrava, both towering figures in Vedic tradition. “Ravana was a scholar, a devoted follower of Lord Shiva, and a king who ruled with wisdom, not tyranny," says Mahesh Pujari, president of the outfit.

“There are many gruesome kidnappings that have happened in the country, but why is only Ravana a demon king?" he asks, adding that his story was not one of mere villainy but a complex narrative that deserved respect.

As the petition gathers momentum, younger scholars raise another question: "Why should we tear apart a Brahmin’s effigy in public every year? If we honour Krishna's dhoti in Mathura, Hanuman’s loincloth, and Sita’s purity, why not show the same reverence for Ravana's character?"

The heart of India is a land rich in diverse traditions, and one such tradition unfolds in the tribal hamlet of Jamuniya, 470-km from Mandsaur, deep in the heart of Chhindwara district, where the story of Ravana takes on an entirely new form — Raven Pen.

The Gond tribals of Jamuniya have their own version of Ravana, one that differs significantly from the mainstream narrative. For them, Ravana was not the tyrant of Lanka, but a figure of protection and spiritual significance. The villagers called him Raven Pen, and for over a decade, families have been installing idols of Raven during the nine-day festival of Navratri.

The idol of Raven Pen is placed in pandals, where the community prays and performs sumarni, a form of remembrance to their deities. The rituals are steeped in the Gond traditions of Khandrai Pen, Khairo Dai, and Meghnad Pen, deities of protection and good health.

Villagers like Virendra Sallam explain, “For us, Raven Pen is a protector, not a villain. We’ve been installing this idol for over a decade, and some families have been doing so for much longer. It’s a tradition we’ve preserved.”

The Gond community’s respect for Raven Pen is in direct contrast to the larger Hindu narrative of Ravana as a demon. Yet, for the people of Jamuniya, Ravana’s legacy has been absorbed into their beliefs, creating a space where the demon king is both honoured and celebrated.

When the effigies of Ravana will go up in flames across the country a day from today, in Khanpura, Jamuniya, and Ujjain, Ravana will stand tall — his story one of reverence, respect, and the reclamation of cultural identity.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines