The Bengal Files: Banned by no one, watched by even fewer

A grandson of Gopal Pantha, a pivotal figure in the film, moved Calcutta HC seeking to stay the release and have scenes removed

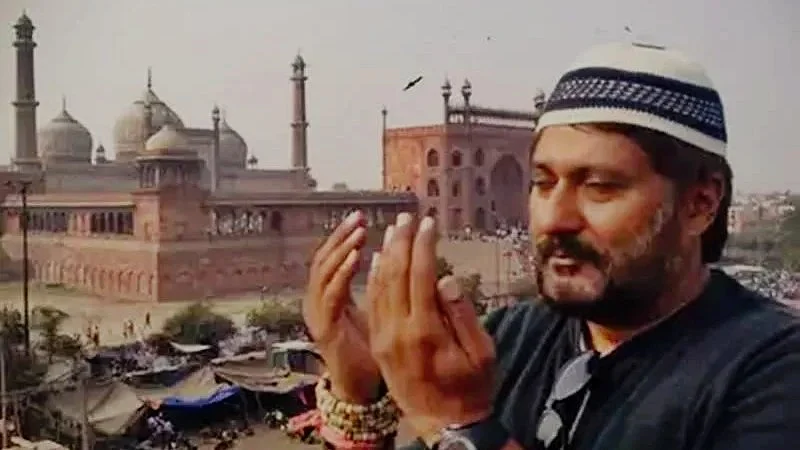

Despite weeks of high-decibel marketing, impassioned video pleas, and the familiar rallying cries of victimhood, filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri’s The Bengal Files has delivered a performance at the box office as flat as its character arcs.

Touted as the third and 'most explosive' instalment of Agnihotri’s Files trilogy — after The Tashkent Files (2019) and The Kashmir Files (2022) — the film ostensibly set out to narrate the saga of the horrifying communal riots triggered by Direct Action Day in 1946 Bengal. What it did not anticipate was an unplanned twist: audiences simply didn’t show up.

According to data from industry tracker Sacnilk, the film earned a modest Rs 0.3 crore on day 11, taking its total earnings to Rs 14.4 crore. This pales in comparison to the filmmaker’s earlier outings, especially The Kashmir Files, which was a surprise commercial juggernaut in 2022.

A muted occupancy rate of 16.65 per cent on 15 September, a Monday, signals what many industry analysts delicately call 'a significant decline' — or, in less diplomatic terms, a box-office collapse.

Banned or just ignored?

While The Bengal Files is technically not banned anywhere, Agnihotri has taken to social media and press interviews claiming an “unofficial ban” in West Bengal, accusing the ruling Trinamool Congress of intimidating theatre owners. A closed-door screening had to be arranged on 13 September at the National Library in Kolkata, under tight CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force) security.

“This government has proved there are two Constitutions in Bengal,” Agnihotri declared at the screening, as if unveiling a geopolitical thriller rather than a lukewarm period drama. “I appeal to all Bengalis to resist this censorship.”

In a video posted days earlier, he had begged West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee 'with folded hands' to allow the film to screen. “It’s disheartening that a film about Bengal is not being shown in Bengal,” he said, omitting to state that no such ban had been officially declared — and that similar disinterest was evident in the rest of the country too.

Kolkata Police responded with administrative brevity: no permission had been sought for any public event related to the film.

Not that Agnihotri has given up trying. On Tuesday, a smattering of people representing an obscure Hindutva organisation gathered in front of a couple of Kolkata theatres to raise half-hearted slogans in favour of the film. But nobody, not even the police, paid any attention. Much like the film, this particular protest sank without a trace.

Politics, pathos and poor reviews

Agnihotri’s core supporters and promotional machinery insist the film is a bold and much-needed retelling of Bengal’s communal past. But many critics — and a vocal segment of social media — see it as another attempt to peddle toxic communal narratives under the banner of historical correction.

The grandson of Gopal Pantha alias Gopal Chandra Mukherjee, the pivotal historical figure in the film, even filed a case in Calcutta High Court seeking to stay the release and have scenes removed. The court dismissed the petition, but the controversy added to the film’s pre-release noise.

Unfortunately for Agnihotri, the cinematic product failed to match the controversy it courted. Viewers on social media called it “too boring”, “clunky”, and “flat-out propaganda”. One reviewer asked: “Why does every male Bengali character look like a villain from a 90s Doordarshan soap?”

Even YouTuber and political commentator Dhruv Rathee weighed in, calling it “a crime” to allow children to watch what he described as manipulative content.

The usual suspects and the unusual silence

The cast, which includes veterans Anupam Kher, Mithun Chakraborty, Pallavi Joshi (also Agnihotri's wife and one of the film's producers), and Darshan Kumar, delivered emotive performances, though many critics felt they were weighed down by the script’s single-minded moral positioning. That the film’s dialogue read like it was written in all caps hasn’t helped its cause.

Notably, the otherwise vocal pro-establishment influencers who had amplified The Kashmir Files have been unusually restrained this time around. Some offered obligatory tweets of support, but none of the viral momentum that propelled Agnihotri’s previous outing was visible this time.

Perhaps it’s fatigue. Perhaps it’s the competition (Baaghi 4 and The Conjuring: Possession) offering viewers more traditional thrills. Or perhaps — and here’s the big one — audiences are starting to distinguish between political drama and cinematic drama.

A movement or a misfire?

In his own words, Agnihotri declared the 13 September screening a 'historic moment.' He described the venue — fortified by armed security — as resembling a “war zone,” which might’ve been true, though in this case the enemy seemed to be public apathy.

Swapan Dasgupta, BJP national executive member and president of the cultural group Khola Hawa, which organised the screening, said: “People in Bengal have the right to see the movie, and that curbs on its screening are undemocratic.” He did not address why people in other states weren’t turning up either.

Agnihotri has since urged Bengalis to launch a “movement” against the West Bengal government’s “atrocities” of not showing the film. With dwindling ticket sales, that movement may need more than moral outrage — it may need marketing, momentum, and above all, a movie worth watching.

So far, The Bengal Files appears to be a case study in the limits of grievance as a promotional strategy. While the director continues to position himself as a fearless truth-teller standing up to state censorship, the market seems to be offering a different kind of verdict — one that plays out silently at the ticket counter.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines