Operation Polo and the integration of Hyderabad: a slice of history

On the 78th anniversary of 17 September 1948, when India’s Deccan heartland was forged in the shadow of the sword

In the sweltering September of 1948, as monsoon rains lashed the Deccan Plateau, a swift and decisive military manoeuvre reshaped the map of a newborn nation. Operation Polo, euphemistically dubbed a “police action”, lasted a mere five days — but etched itself into the annals of Indian history as the catalyst for unifying one of the Subcontinent’s most enigmatic enclaves.

On 17 September 1948, the princely state of Hyderabad — a glittering jewel in the crown of Mughal legacy — formally surrendered its sovereignty, signing the Instrument of Accession. This pivotal moment not only quelled a brewing secessionist storm but also underscored the fragile alchemy of diplomacy, force and national resolve in the chaotic aftermath of Partition.

Now, 77 years later, the echoes of Operation Polo resonate amid raging debates on federalism and identity. In an era of border skirmishes and regional assertions, the Operation serves as a stark reminder of the costs of disunity — and the enduring imperative of cohesion. For today, commemorations planned across Telangana and beyond will blend solemn tributes with critical reflections, urging a reckoning with the violence that accompanied victory and the secular ethos it ultimately enshrined.

* * *

Hyderabad’s story begins not with rifles, but with riches.

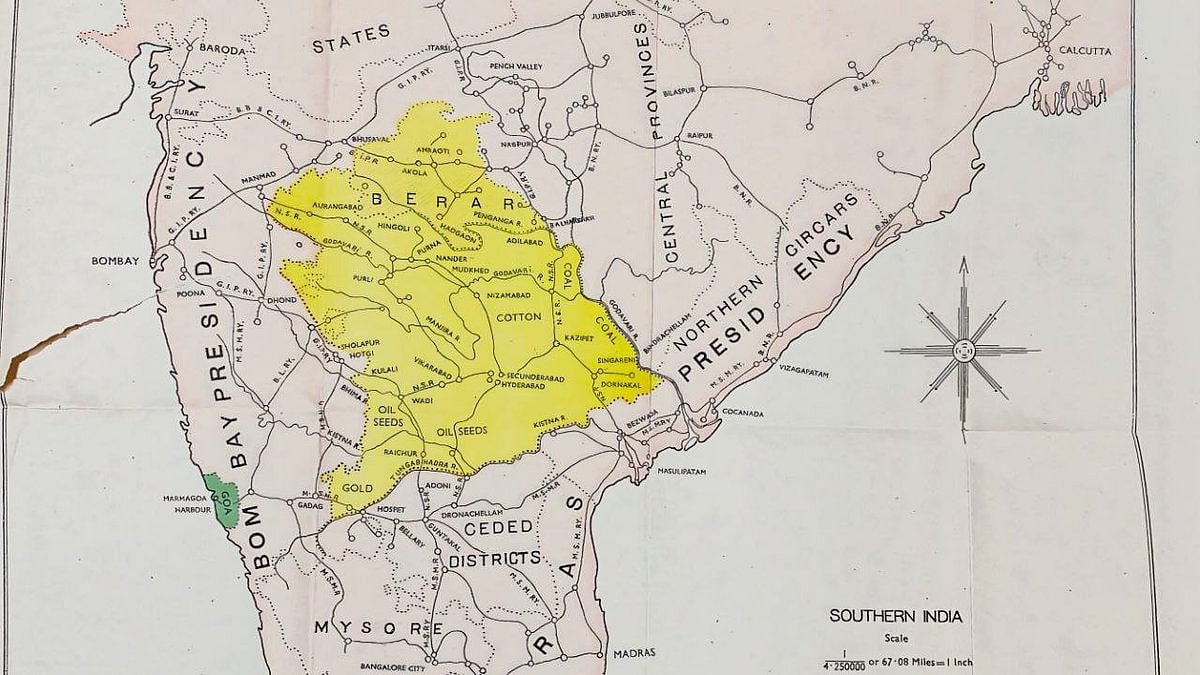

Spanning nearly 83,000 square miles, the state was a polyglot realm where Telugu rhythms mingled with Marathi cadences, Kannada whispers and Urdu poetry. Its ruler, Mir Osman Ali Khan, the seventh Nizam, commanded a fortune that once made him the world’s wealthiest man, his vaults brimming with jewels that could eclipse the sun.

Yet beneath the opulence lurked asymmetries: a Muslim nobility lording over an 85 per cent Hindu populace, with administrative sinecures skewed toward a tiny elite. Hindus, despite their numerical dominance, held scant sway in the bureaucracy or barracks, fostering a simmering discontent that predated Independence.

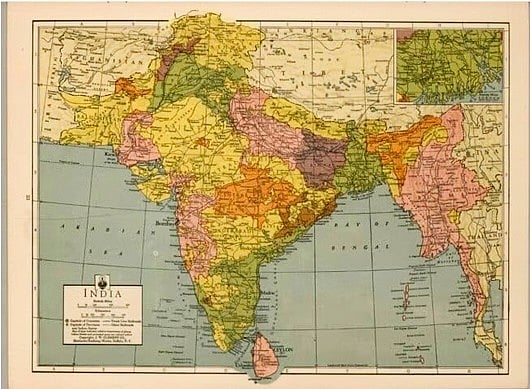

When the British Raj dissolved in 1947, the princely states — over 500 in number — faced a trilemma: join India, align with Pakistan or declare autonomy.

Most rulers, swayed by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s iron-fisted persuasion, opted for accession. Hyderabad, however, stood apart.

Geographically landlocked yet strategically vital, it bisected the Indian heartland like a dagger poised at the nation’s core. The nizam, envisioning a sovereign buffer under a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth, rebuffed overtures from Delhi. His overtures to Lisbon for a Goan corridor to the sea only heightened suspicions of external meddling.

Internal fissures exacerbated the standoff. The Telangana countryside, a tinderbox of agrarian grievances, erupted in peasant revolts backed by communist insurgents. These uprisings, blending class warfare with anti-feudal fervour, challenged the nizam’s grip.

Enter the Razakars: a paramilitary cadre spawned by the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, a communal outfit founded in the 1920s to bolster Muslim solidarity.

Led by the fiery orator Qasim Razvi, these irregulars morphed from volunteers into vigilantes, enforcing a vision of Islamic primacy through terror. Hindu villages bore the brunt — looting, abductions and massacres that displaced thousands and ignited retaliatory flames across borders.

Delhi watched with mounting alarm.

Prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, ever the idealist, championed negotiation, viewing Hyderabad as a “dangerous possibility” that could splinter the republic. Patel, the steely architect of integration, saw it as an “ulcer in the heart” demanding excision.

A standstill agreement in November 1947 promised stasis, but violations piled up: Razakar raids on Indian soil, economic chokepoints throttling trade and whispers of Pakistani arms flowing southward. By mid-1948, skirmishes at border outposts like Kodad had drawn first blood, tipping the scales toward confrontation.

The Five-Day Storm

The morning of 13 September 1948 broke with the rumble of Indian armour. Operation Polo, orchestrated by Major-General J.N. Chaudhuri, mobilised 35,000 troops across three fronts: from Solapur in the west, Bhopal in the north and Cuttack in the east. The codename evoked equestrian flair, but the execution was brutally efficient — a blitzkrieg tailored to a foe outmatched in materiel and morale.

Hyderabad’s defences crumbled like dry earth under monsoon fury. The Nizam’s 22,000-strong army, supplemented by 20,000 Razakars, couldn’t withstand the onslaught with their outdated rifles and fervent zeal.

At Naldurg Fort, the opening clash saw Gurkha rifles silence Hyderabad’s infantry in hours. Aerial Tempests from the Indian Air Force strafed ambush points near Rajeshwar, clearing paths for mechanised columns. By 14 September, Latur and Mominabad had fallen, their garrisons yielding after token resistance from the Golconda Lancers.

Razakar guerrillas ran hit-and-run forays, their fanatic zeal causing momentary havoc. Yet Indian artillery — 75mm guns thundering from hillocks — shattered their lines.

In the east, Bidar capitulated quietly; in the west, Hingoli’s fall isolated Secunderabad. The nizam, ensconced in his King Kothi Palace, dispatched envoys pleading for UN mediation — a gambit that had earlier stalled in New York but now rang hollow amid the advancing tide.

By 16 September, the noose tightened around the capital. Razvi’s rhetoric of hoisting the Asaf Jahi flag over Delhi dissolved into desperate ambushes.

At 5 p.m. on 17 September, with Indian tanks idling on Hyderabad’s outskirts, the nizam broadcast a ceasefire. General Syed Ahmed El Edroos, his commander, tendered an unconditional surrender, averting a bloodbath in the city. Chaudhuri’s armoured spearhead rolled in the next day, greeted not with fanfare but the weary relief of many residents long terrorised by Razakar depredations.

The toll was grim. Official tallies pegged Hyderabad’s losses at over 2,000 combatants, with thousands more detained in sweeps that blurred justice and vendetta. Civilian carnage, shrouded in secrecy until the 2013 declassification of the Sunderlal Report, claimed 30,000–40,000 lives — predominantly Muslim villagers caught in reprisal crossfires.

These “hidden massacres”, as chroniclers later termed them, scarred the Deccan, fuelling narratives of ethnic cleansing that linger in oral histories and partisan polemics.

* * *

The Instrument of Accession, inked on 17 September, dissolved Hyderabad’s autonomy overnight. The nizam, stripped of real power yet retained as a titular rajpramukh, became a ceremonial relic in the new order. Chaudhuri assumed military governorship, imposing martial law to dismantle Razakar networks and quash communist holdouts.

By January 1950, civilian administrator M.K. Vellodi orchestrated elections, weaving Hyderabad into the democratic fabric.

The state’s multilingual mosaic fed into the 1956 linguistic reorganisation, birthing Andhra Pradesh and seeding Telangana down the line.

* * *

The import of Operation Polo transcended cartography. It fortified India’s territorial sinews, preempting a balkanised Deccan that could invite foreign proxies. As the last major holdout after Junagadh and Kashmir, it burnished Patel’s legacy as unifier, proving that velvet gloves concealed iron fists when sovereignty hung in balance.

Secularism, too, emerged fortified: a Muslim potentate yielding to a Hindu-majority republic without doctrinal rupture, affirming the Constitution’s pluralist vow even as communal embers smouldered.

Yet the Operation’s shadow endures.

At the time, detentions swelled to 18,000, jails bursting with Razakars, Hindu chauvinists and leftists — many ensnared by local grudges. The Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, Razvi’s ideological cradle, was proscribed before it was resurrected as the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, its modern avatar navigating Hyderabad’s politics with echoes of that turbulent ethos. Razvi himself languished for a decade in Vellore Fort before his exile to Pakistan, his venom unquenched.

Echoes on the 78th dawn

Today, on 17 September 2025 — the 78th anniversary of this seismic merger — India confronts Polo through a prism of maturity and myopia.

In Telangana, where Hyderabad’s ghost lingers in gleaming minarets and resilient bazaars, events will honour the ‘liberation’ while interrogating its brutal underbelly. Seminars at Osmania University, folk recitals evoking peasant ballads and the laying of wreaths at sites of surrender will juxtapose triumph with trauma, drawing parallels to today’s federal frictions — from farm laws to frontier disputes.

This milestone arrives amid performative nationalist rhetoric that invokes Patel’s resolve yet risks glossing over minority anxieties.

Operation Polo teaches us that unity, when forged in haste, demands vigilant nurture: addressing agrarian echoes in Telangana’s cooperatives, bridging linguistic legacies in bilingual policies and healing communal wounds through inclusive governance.

In a world of fracturing alliances, the Deccan’s defiant integration whispers a timeless truth — nations are not merely maps, but mosaics mended by memory and magnanimity.

The scars of 1948 remind us that true sovereignty blooms not from conquest alone, but from the courage to confront its costs.

Hasnain Naqvi is a former member of the history faculty at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. More of his writing may be read here

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines