Jail makes you a different person: Kashmiri journalist Fahad Shah

Imprisoned for 21 months on terror charges, Shah finally walked free in November. On World Human Rights Day, here are the traumatic details of his incarceration

Fahad Shah, arrested on 4 February 2022 and subsequently booked in four cases, three under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), had received bail in three. On 17 November 2023, bail was granted in the fourth case, where he was charged with conspiracy to commit a terrorist act in April 2022 for an article published more than 10 years earlier in the digital magazine he had launched as a 21-year-old.

Justice Mohan Lal and Justice Atul Sreedharan found no laws were broken by the allegedly “highly provocative” and “seditious” article titled ‘The Shackles of Slavery Will Break’, written by research scholar Abdul Ala Fazili, who remains incarcerated. Nor was there evidence it had caused young men to join the Pakistan-backed insurgency raging in Kashmir since the early nineties.

The Indian government’s scrutiny of the media in Kashmir intensified after Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won a second term in May 2019 by a huge majority in Parliament and, three months later, rammed through the rescinding of Jammu & Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status, demoting the country’s only Muslim-majority state to a Union Territory under the control of the Centre.

What followed was a seven-month internet shutdown and a concerted effort to rein in reporters in a region which, even as it suffered a long-running conflict and became one of the world’s most heavily militarised zones, had a fairly robust media reporting on its embattled people and the issues of human rights, governance and livelihood.

Post 2019, journalists were summoned and interrogated more frequently. Homes were raided. Reporters were accused of grave crimes against the State and arrested, or stopped from flying out of the country. Long-running dailies dependent on government advertisements were forced into submission. Since the BJP came to power in 2014, India’s ranking on the world Press Freedom Index has steadily declined — it currently ranks 161 out of 180 countries. Journalists were targeted for ‘anti-national’ reporting across India, but nowhere more than in Kashmir.

Shah was freelancing while trying to run The Kashmir Walla on an international grant, with appeals for subscription. As the intimidation of journalists in Kashmir intensified, Shah grew more vocal on social media and continued publishing despite police interrogations. He was nominated for the RSF (Reporters Without Borders) Prize for Courage in 2020 and awarded the 25th Human Rights Press Awards 2021 for reporting on the Delhi riots.

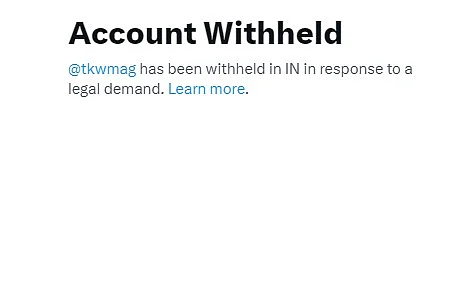

His arrest in 2022 precipitated the death of critical coverage in Kashmir. In August 2023, the skeletal staff remaining at The Kashmir Walla said the government had blocked their website, and they could no longer access their social media accounts. While granting bail to Shah, the high court judges said they did not find anything illegal about the compilation of articles submitted to them by the prosecution.

The judges removed the charges of conspiracy to commit a terrorist act (section 18 of the UAPA), the offence of waging war against the Government of India (section 121 of the IPC), and assertions prejudicial to national integration (153-B IPC) but retained section 13 of the UAPA (unlawful activities) without giving any reason.

They also charged him under the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, taking a prima facie view that the appellant had received remittances from overseas without intimating the authorities about it.

The fear of retribution, even after being granted bail by the high court and the case largely demolished, is echoed in the silence of other Kashmiri journalists in the wake of a significant victory for Shah and another Kashmiri journalist, Sajad Gul, whose preventive detention was also quashed by the high court in December.

Have you read the order?

There were some pretty heavy sections. It is a relief that the judgement has come, and the court has given me bail, which I had been waiting for, for a very long time. I haven’t read the whole thing yet.

How are you feeling?

That is a big question. I’m trying my best to get back to where I was mentally and physically. It’s is very hard. Things have changed. People are loving and caring. That has been helpful. But once you are away for a long time, there is detachment. One moment you are here, and the next, you are there.

Suddenly you wonder, ‘why am I at home?’ I picked up habits like taking a restless walk in the middle of the night and sitting in very odd positions. My stomach can’t take normal food. Mentally, you are torn apart. You have to stitch yourself together. You are in tears. I felt okay, but now something is strange. I never felt so exhausted. I forget things.

Are you saying you are more uncomfortable out than in?

It’s not uncomfortable; there are just too many things that you are trying to focus on.

Did you anticipate being jailed? You were very vocal. Were you mentally prepared for it?

I was getting summons for two years. There was a lot of pressure. Mentally, you may be prepared, but when it happens to you, you realise, oh my God. Somebody asked me if I knew what it would be like. What I know is from books and movies.

Anybody who has not gone to prison doesn’t know what it does to you. Every hour was a struggle. Every breath was a battle. Every day was like a mighty hilltop. It is like being chained to a stone that has been thrown into the sea. You try to swim but you can’t.

It must have been terrifying.

There were too many things. One case after another. I was being picked up from one place and taken to another, and another. It was a continuous trauma. You broke again and again. You would get up, something would happen, and you would fall down again.

How did you begin to cope?

It was very painful to deal with at the start. When you are in custody, you are alone. But when you go to prison, there are a lot of people—a community forms. You hear them. They hear you. Many legal discussions happen: ‘My lawyer is saying this. Should I write another application?’ You start doing all the jail stuff. Priorities change. Things change. You get busy studying, reading and praying. You feel better.

You have to make peace with your life there, but you are always on your toes. I remember a few days after I got bail, people said, “Now you have to leave. Have you packed?” I didn’t have anything to pack. I would take the clothes out of my bag, wash them and put them back into the bag. Just my books, my pen and diary. There was such a ‘thing’ about the packing. It wasn’t like I had rented a room there! I kept thinking, I will get out today, I will get out tomorrow.

Everyone has this hope. When you see people leave, you get happy. You think if he has got out, so will I. If he has got bail, so will I. When I got out, everyone came and hugged me. It was really nice. Those bonds you make inside help you survive and get through the struggle.

Were there other journalists?

I was the only journalist there. Because this was covered in the news, people knew when I was expected. I went to Kupwara jail, and people called my name and said, “We thought you were coming yesterday.” The same thing happened in Jammu. People knew everything.

Who were the other inmates?

They were from all walks of life: shopkeepers, labourers, students, teachers, people from the private sector.

What were they accused of?

Every kind of crime: murder, drug cases, militancy-related issues, the Public Safety Act, UAPA cases. Many different cases from many different places.

Did you know there was a conversation about you outside?

Not really. When you are in jail, even if there is a story on the front page about you, you feel nothing is happening until a judge says you are free to go. You don’t really know what is going on outside. The Express, The Hindu and the Frontline carried the news, but I didn’t really know if that would help or make things more difficult. In the end, what matters is what happens inside the court.

Are you happy to be out?

I’m happy. I want to read. I did read, a lot. I would say The Hindu is one newspaper that should be sent to every jail in the country. It played a huge role in my prison life. I read it religiously. The 8-page literary magazine on Sunday was my thing. They had big features, profiles, book reviews. I thought, once I get out, I will read these books. I did the Sudoku every day. I became a Sudoku master in prison.

Did you have visitors?

I had told my parents not to come. It was very far, with bad roads. Besides, there is a glass (pane), then a mesh. You have to pick up a receiver like in the movie Shawshank Redemption: ‘Hello, yes, how are you?’ It is very tragic. You can’t even touch them. You can’t hug them. So, I told my parents not to come. My brother came twice. Someone else came once. That’s it.

You feel terrible when you see someone leave and you have to go back inside. I found the whole experience very traumatic. I didn’t want to go through that.

Did you have moments when you thought you may never come out?

There were many dark moments. You know, I had this condition where I couldn’t cry, and my doctor gave me eyedrops. I used to joke with my friends that I had to cry. When I went inside, I cried, often.

When you have no connection with the world outside, you imagine very dark things, especially when your parents are old, and you are very close to them. I broke down many times. Once, I collapsed because I heard my mother was not well. I had palpitations. They had to medicate me. Suddenly, I was crying in front of 17 people in the barracks. Others had moments of weakness too. Someone goes to the washroom to cry. Someone harms himself. There are so many things that happen in prison that you can’t explain, even to your own family.

Your own family can’t understand what you are going through. In prison, you and the other inmates are fighting the same battle. They are your family. They help you cope.

What did you think of most of the time?

About my case — bail, hearings. You also think about what to do with your time, you can’t just sleep for 24 hours. You put your energy into something. As a Muslim, you pray five times a day, you learn more about your faith, you recite the Quran. It helps you feel better. I was writing and reading. I thought about things I had studied in university. I was trying to make sense of what prison does to you and others.

Did you regret doing the work you did? There must have been conversations where your parents told you to stop, and you didn’t.

I don’t want to say anything about work, but I felt really bad about what my parents had to go through. They did not deserve this. I always wanted to be the reason for their happiness. When I became the reason for their pain, that really affected me very badly.

Are you a different person from the person who went in?

Completely. There are some things that I don’t want to talk about. Maybe someday, maybe never. Albert Camus wrote: struggle humanises you. I think that happens, to some extent. When you go through a recurring struggle and you battle every day, it changes you. You lose your ego, your desires become minimal. You see people differently.

You treat people differently. Jail is where you have so much time to reflect on your whole life. Many things vanish inside the person you were, and many new things emerge. That struggle makes you a better person. You become kinder.

Arrogance goes away completely because you are nobody in this huge world. Just be kind to people because, at the end of the day, you are going to die, and that’s it. That’s the end of the story. People inside would say, think about why God has sent you here. You pause and see things you didn’t see before.

Do you have trauma? Will you seek help for it?

I was already seeing a psychologist. Yes, there is trauma. Many things don’t make sense. In 21 months, you see a lot. You see violence, you see people breaking, you see people losing hope. This one inmate found out his mother had passed away, he kept screaming and crying and falling unconscious. All of us were crying. Everyone was reminded that it could happen to us.

Those moments are very dangerous. They break you. It is not a trauma that hits you once. It hits you slowly. It decays you slowly. That is why it takes time to get out of it. It’s not so simple that you come home and it’s great. The things that I may never say will stay with me forever.

Tell us about the moment you got bail and left prison.

I heard on the 17th (of November) that they had given me bail and dropped the charges. I didn’t know any details. I told everyone. They were all very happy. When the order came, I thought, this time I might actually be walking out. But there was no surety. It was my fourth bail. There was a big weight on my shoulders because my bail was reserved for 2.5 months. Those were really long months. I felt they may have rejected it.

When I was called and told my pass had come and I had to leave, I packed my bags and bid farewell to everyone. I had to wait for about an hour for some formalities. When the prison guard signed that diary, the last words he said to me were, “Now, don’t come back again”. I said, “Never again.”

What was it like meeting your parents?

It was amazing. My father cried. My mother cried. They were affected by how I looked. It started sinking in slowly that I could sit down and talk to them. It was the first time I had tea at home, with everyone looking at me. That is when it hit me. I was finally free and with my family.

Betwa Sharma is the managing editor of Article 14. Courtesy: Article 14

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines