Fortified rice: Public policy served raw

What explains the Modi government's cavalier decision to universalise fortified rice? An investigation

On 15 August 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi mounted the ramparts of Delhi’s Red Fort, a place that tempts leaders to make grand speeches to the crowd below. He announced that more than half of India would be fed rice fortified with micronutrients by 2024 to eradicate anaemia. But in his haste, he served a public health policy that was raw and potentially dangerous to health.

Documents accessed by The Reporters’ Collective reveal that while going ahead with the decision, Modi ignored the fact that the majority of pilot projects launched by his government to test the rice’s nutritional impact had not taken off at all.

The government overruled the finance ministry’s red flag calling the move ‘premature’ before understanding its impact on human health. Sacks of fortified rice were trucked out despite the head of the country’s leading medical research body calling for wider consultations, following ‘serious concerns’ on the ‘adverse effects’ of fortified rice on children.

But Modi, unhindered by internal and external warnings, announced the government’s plan to mandatorily supply fortified rice to over 80 crore Indians, most of them poor, under all food security schemes. So far, in order to mitigate rising incidence of anaemia and micronutrient deficiency, the central government has allocated over 137.74 lakh tonnes of fortified rice to the states for beneficiaries of different welfare schemes.

Official data shows that over 1.7 million children in India are classified as ‘severely acute malnourished’. Of particular concern to public health activists is the rise in anaemia—caused by deficiency in dietary iron.

Overall, it’s estimated that 67.1 per cent of children under 5 years of age and 57 per cent women between 15 and 49 years of age in India are anaemic. In 2019–21, anaemia cases among children rose 9 per cent compared to 2015–16. The government claims rice fortified with iron, folic acid and vitamin B-12 will mitigate India’s problem of rising micronutrient deficiency, also called hidden hunger.

Globally, food fortification has been one of the weapons in the war against micronutrient deficiency. In India, the most famous was the campaign to fortify salt with iodine to eliminate goitre. Even as the government powers on with its plans to supply fortified rice under all welfare schemes by 2024, it has simultaneously begun supplying fortified wheat, oil and milk under select welfare schemes in some states.

Experts say the artificial injection of micronutrients by fortification is not a

long-term solution. They say a diversified diet and adequate food delivered at affordable prices are the solutions. But in the past, to cut costs, the Union government has actively worked to either diminish or restrict access to fresh, nutritious food under its various food security schemes. And now it has fallen back on supplying artificially fortified food to improve the population’s health.

But science hasn’t yet given a thumbs-up to fortified rice.

Fortified rice is made by beating rice grains into a dough, adding micronutrients to it and then machine-carving the dough back into grains that resemble rice. One such artificial kernel is mixed with 100 normal rice grains.

To test if such fortified rice really cures anaemia and other micronutrient deficiencies like stunting and wasting, the government launched test projects under a pilot scheme in February 2019. The testing was to continue until March 2022. But instead of waiting for the results of all the pilot projects, Prime Minister Modi announced a full-blown scheme in 2021, affecting over half of the country’s population.

At the point of this announcement, 9 of the 15 pilot projects planned across 15 states that consented had not even taken off. But government officials took Modi’s Independence Day announcement as a call to action and even cited the Prime Minister’s speech when seeking administrative approvals for the scheme.

The states didn’t show much appetite for the pilot scheme, and rice was supplied in just six districts—one district per state—at project half-time. And four states started distributing rice just after Modi’s Independence Day speech. Result: The pilot scheme flopped.

“So many people questioned us about why our pilots were not successful,” said Sudhanshu Panday, then secretary at the food and public distribution department, at a seminar held in Delhi on 25 October 2021. “We had started pilots in 15 states—one district in each of [the 15] states. But there were fundamental problems in the pilot,” he said, adding that “the problems were purely logistics and supply-side related”. He did not comment on how these pilots with their fundamental flaws could have been expected to generate valid scientific results.

India’s State-run think tank NITI Aayog’s senior adviser Anurag Goyal too, in an internal meeting with the government on universalising the scheme, admitted that the pilots were “not very successful”.

But when asked about the success of the pilot projects in Parliament on 5 August 2022, the women and child development ministry lied: “The pilot was successful in ensuring the ecosystem for fortified rice throughout the country.” It said that the pilots allowed key players in the scheme to prepare for a universal scale-up. However, it remained mum on the impact of fortified rice on nutrient deficiency, despite it being one of the key objectives of the pilot.

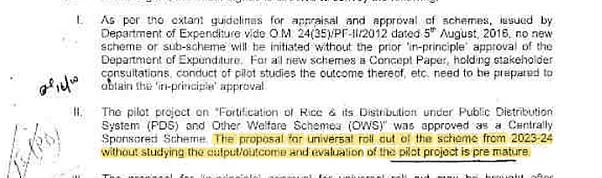

The department of expenditure, in an office memorandum, warned in 2019 that universalising fortified rice supply without first studying the outcomes of the pilot project is premature.

The Collective sent detailed queries to the NITI Aayog, the food and public distribution department and the women and child development ministry. None of them responded despite reminders.

One questionable pilot

The only research the government had to bank on before it moved to universalise fortified rice was a Tata Trusts study from a pilot project in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district.

The pilot project, which began in November 2018, focused on Bhamragad and Khurkheda villages, with a total population of 1,22,398.

In reply to another question, the government told Parliament that the study had shown fortified rice was ‘useful’. It did not mention the actual results of the study.

“The Maharashtra government had conducted an evaluation study regarding the effectiveness of rice fortification and found it useful,” Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti, MoS, ministry of consumer affairs, told Parliament on 27 July 2021.

The Reporters’ Collective accessed the study. It also asked Tata Trusts to respond to queries on it. ‘The pilot found a positive change in the target categories of the two programme blocks in Ghadchiroli, and that such a programme was feasible,’ a Tata Trusts spokesperson informed The Collective over mail.

The study shows improvement in the haemoglobin levels of those served fortified rice for 11 months. But the study also shows that mothers in the age group of 19–49 years who were served fortified rice had shown reduced smoking habits by 30 per cent, while those who were not had cut down smoking by only 8 per cent.

The study results also show that consumption of alcohol increased among mothers in the age group of 19–49 by 350 per cent when they were not served fortified rice and by only 21 per cent when they were served the fortified staple. The scientists behind the study and Tata Trusts itself did not explain in the study how or why they correlated fortified rice consumption to the smoking and drinking habits of these mothers.

In their response, quite incredibly, Tata Trusts also stated, ‘The full immunisation status was also found to have improved in both intervention blocks. The treatment/care at the health centre for medical problems of children had also improved.’ Again, it did not elaborate on how this could be linked to the consumption of fortified rice.

Experts that The Collective spoke to say the study is “very poorly designed” and pointed out that neither have the results of the pilot project been published in any journal nor are they peer-reviewed. The focus of the pilots, public health researchers have previously pointed out, seems to be more on logistical feasibility rather than impact on nutrition.

So 18 days after the government’s reply to Parliament claiming the Tata Trusts study had been useful, Prime Minister Modi announced the plan to supply fortified rice across the country even as the government’s pilot scheme had collapsed.

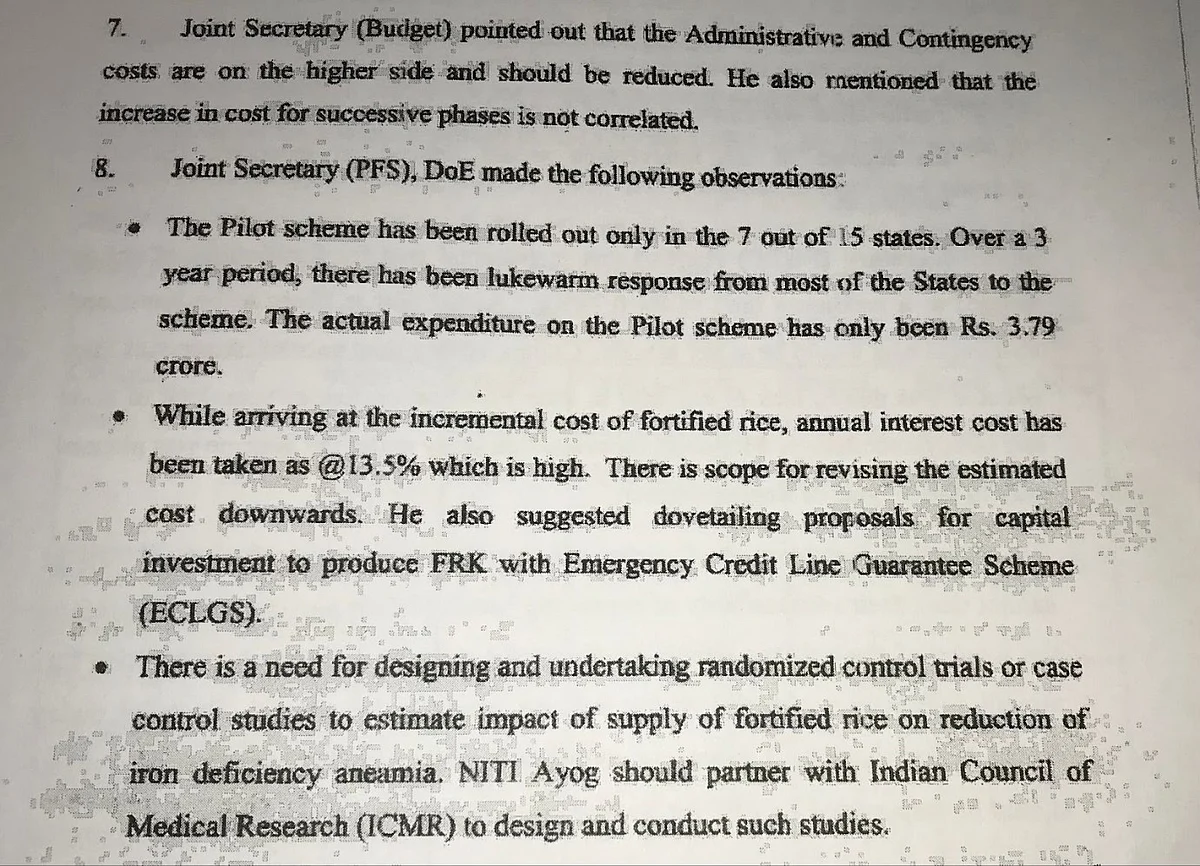

While government officials insisted in Parliament that pilots had been successful, bureaucrats internally admitted to the lacklustre response and need for more evidence to study the efficacy of fortified rice.

Served in haste

With their pilot projects failing, the government instead relied on cherry-picked studies to justify supplying fortified rice to over 80 crore citizens.

In June 2021, the department of food and public distribution compiled a list of 13 research papers for an internal presentation to consumer affairs minister Piyush Goyal, whose ministry is responsible for the procurement and distribution of fortified rice.

A closer look at this evidence the department compiled raises more questions about the decision to supply fortified rice.

While 11 of the 13 studies on the list showed the efficacy of fortified rice, two explicitly said that fortified rice has little effect on iron, vitamin A and haemoglobin levels.

Another paper on the list used to justify the use of fortified rice is co-authored by a researcher who has been publicly warning of the risks of fortified rice!

Curiously, the food department omitted a review by Cochrane, a UK-based scientific non-profit whose evaluations, experts The Collective spoke to say, are considered a gold standard on the efficacy of fortified rice in scientific literature.

The Cochrane review aggregates evidence from many studies on the efficacy of fortified rice and analyses their results. In the case of fortified rice, its analysis of 17 research papers found no mention in the presentation. Out of the 13 papers in the food department’s list, six were reviewed by Cochrane. This review showed that ‘fortification of rice with iron alone or in combination with other micronutrients may make little or no difference in the risk of having anaemia or presenting iron deficiency’.

The researchers further noted, ‘We are uncertain about an increase in mean haemoglobin concentrations in the general population older than 2 years of age.’

“One thing is very clear, the Cochrane Review is the most respected source of evidence globally,” said Dr H.P.S. Sachdev, who serves as senior consultant for the Union government’s Food Safety and Standards Authority of India’s (FSSAI) panel on nutrition and fortification. The FSSAI would later go on to classify the fortified rice kernel under the “high-risk category”, which means that if it is not manufactured properly, it can lead to devastating health effects.

“I would go by that [Cochrane review]. I have gone through the review. Excellent review with standard methodology. Even if there is evidence that has come [after the review was published] which shows positive results, it must be [taken together with] that. We need to look at overall conclusions,” he added.

The food department’s list of evidence also includes a 2004–05 study in Bengaluru schoolchildren that found a decline in iron deficiency among those who were fed fortified rice. But it also noted an increase in levels of a protein called serum ferritin—linked to a rise in the risk of diabetes.

One of the seven authors of this study was Dr Anura Kurpad, who is a member of NITI Aayog’s national technical board on nutrition. He has been publicly warning of the risks associated with high ferritin levels.

Dr Kurpad’s trial that showed a potentially dangerous increase in ferritin now finds itself on a list that, ironically, the government presents as evidence of rice fortification’s efficacy because it showed a dip in iron deficiency in school children.

But why should people worry about fortified rice when salt, similarly fortified with iodine, has been consumed by millions across the country for more than half a century?

“One of the reasons salt fortification is probably successful is because it’s very hard to overeat salt,” Dr Kurpad explained to The Collective.

“At some point you’re going to say that the food is too salty and don’t eat it. Rice, on the other hand, is very easy to overeat.”

Experts also pointed out that unlike iron, excess amounts of iodine leave the body through urine. There is no natural way for the body to rid itself of excess iron.

“Our study was focused on very poor people,” Dr Kurpad told The Collective over phone. “Secondly, we were also focussing on iron-deficient people. These studies were not a general, universal thing.”

“If you look at studies around the world that focussed on the general population, they were all put together in the Cochrane review. It showed there’s no benefit of rice fortification [for] anaemia,” he added.

When The Collective asked Dr Kurpad if there had been any discussion on rice fortification’s efficacy at NITI’s national technical board on nutrition, he replied, “No. Not as far as I know.”

The government’s own top medical research body, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), has previously shown that fortified rice had no substantive effect on mitigating anaemia levels among school-going children.

Public health experts have been warning of the risks of mandatory rice fortification.

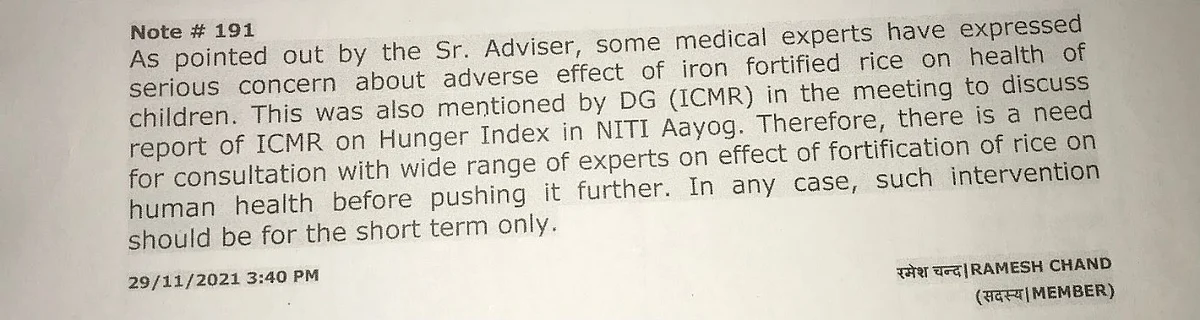

This also made its way to NITI Aayog’s files. Professor Ramesh Chand, NITI Aayog’s member on agriculture, said in November 2021, “Some medical experts have expressed serious concern about the adverse effect of iron-fortified rice on the health of children. This was also mentioned by DG (Indian Council for Medical Research)...”

“Therefore, there is a need for consultation with a wide range of experts on the effect of fortification of rice on human health before pushing it further,” he added. Multiple RTI (Right to Information) requests to the ICMR reveal there have been no consultations on the issue.

Professor Chand in his note added, “In any case, such intervention should be for the short term only.” The government has overruled this suggestion too.

Ramesh Chand, NITI Aayog member, points out in a note on file that experts have ‘serious concern’ over supplying fortified rice to children.

Most experts are wary of adding what are, in essence, medical drugs to food. The medical experts Professor Chand referred to in his file note have been vocal in their criticism. One of them is Dr Kurpad. “They’re already running an iron supplementation programme under Anaemia Mukt Bharat. That’s more than enough because it gives a lot of iron. Why on earth would we then want to go for fortification, which is a much weaker method than supplementation?,” Kurpad asked.

Dangerous for people with certain ailments

Fortified rice is also harmful to people suffering from diseases that worsen with iron intake.

“So, we do know that for example, you don’t want to give iron to people with thalassaemia and sickle cell anaemia. We also don’t want to give it to those in the acute phase of tuberculosis,” Dr Vandana Prasad, the founding secretary of Public Health Resource Society, told The Collective.

The food department’s operational guidelines on fortification try to address this concern with a ‘Not recommended for people with thalassaemia and people on low iron diet’ label on bags carrying food items fortified with iron.

The Collective travelled to Jharkhand to review how the fortified rice distribution was working in villages with predominantly tribal communities, which have a higher incidence of sickle cell anaemia.

Jharkhand has the highest number of thalassaemia and sickle cell anaemia patients in the country. The number of people suffering from sickle cell anaemia in Jharkhand is estimated to be twice the national average.

In multiple instances in Kuchiyasholi, a village in Jharkhand’s Purbi Singhbhum district, for several months the gunny bags with fortified rice did not carry the labels that warned of the harmful effects of fortified rice on people suffering from thalassaemia.

Responses to the recent RTI queries by activist Kavitha Kuruganti, which have been reviewed by The Collective, showed that the Centre does not have any means to segregate those suffering from thalassaemia or sickle cell anaemia from among the beneficiaries of fortified rice. Yet the government steamrolled this rice into millions of homes across the country.

PS: After Prime Minister Modi had launched the countrywide scheme, a top government body carried out a review of fortified rice pilot studies. The report was never made public.

This is the first instalment in the series. Read instalments 2 and 3 here.

This investigation was originally published here by The Reporters' Collective (www.reporters-collective.in).

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines