Europe can’t do enough to appease Trump

Cut loose by the US President, Europe is scrambling to re-arm itself, but does it need a new paradigm?

For nearly a decade, Europe has done practically everything the United States under President Donald Trump has spent years demanding. It has increased defence spending year after year. It has hardened borders, both external and internal. It has tightened asylum rules and struck deals with authoritarian governments to prevent migrants from reaching European shores.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the continent has embarked on its most intensive rearmament effort in generations. Yet none of this has earned Europe praise in Washington. Instead, Trump’s new national security doctrine depicts Europe as weak and unreliable.

Why does compliance not have the effect European leaders expect? Even when demands for more tanks, missiles and border walls are met, why is it not good enough? The answer does not lie in budget allocations or policy tools but in worldviews.

Europe does not share Trump’s understanding of what prejudices (kinder people may say ‘values’) should underpin Western power — and by extension, what security means. So, for Trump, Europe will always fall short, no matter how big and strong its armies become or how firmly it closes its borders.

The European Union and its member states have increased military expenditure for ten straight years. The war in Ukraine accelerated the trend dramatically. In 2025, European defence spending is expected to reach more than two per cent of GDP on average, meeting NATO’s original benchmark. Investments in equipment, ammunition and drones are surging.

Poland has become one of the highest spenders. France and Germany are preparing multi-billion-euro procurement drives. The European Commission has launched programmes worth hundreds of billions to rebuild a defence industry downsized after the Cold War. Sweden, which has not fought a war for over 200 years, is planning to up defence spending to 2.8 per cent of GDP by 2026 and 3.5 per cent by 2030.

Also Read: America’s phony war on drug trafficking

For Trump, this is still not enough. He and his Pentagon officials now demand that Europe take over most of NATO’s conventional defence by 2027, a deadline most European experts consider impossible.

Even if the money were available, Europe cannot conjure overnight the soldiers, intelligence networks, command structures, or strategic nuclear systems that the United States has supplied since 1949. Europe is doing what it can, but Trump insists it should replace the United States as the primary defender of the continent within a two-year window or face a partial American withdrawal from NATO coordination.

That is not a negotiation based on strategic realities. It is a stance rooted in the ‘America First’ worldview that sees alliances as burdens. Trump does not see NATO as a community of democracies confronting shared threats but as a transactional service the United States provides, one for which Europeans should pay up quickly and unquestioningly.

As long as Europe insists that transatlantic defence is a mutual project, Trump will accuse Europeans of taking advantage of America even as they pour more and more resources into their militaries.

The immigration story is similar. Since the 2015 refugee crisis, the EU has done nearly everything its far right demanded: it has limited irregular migration, built new surveillance systems, outsourced border policing to states like Turkey and Libya, and imposed tight screening at its frontiers. Even within the Schengen area, where free movement is enshrined in law, more and more states have reimposed border controls.

Many governments have toughened asylum rules to deter new arrivals and speed up deportations. The new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum promises tougher entry procedures and faster removals. In recent years, the EU has increasingly securitised immigration, prioritising border control and deterrence in ways that often sideline basic human rights obligations and international law.

Yet Trump still portrays Europe as a civilisation in decline. His security strategy claims Europe is at risk of becoming unrecognisable within two decades because of immigration and declining birthrates. It echoes far-right conspiracy narratives that claim Europeans are being replaced by non-Europeans.

In this worldview, Europe’s problem is not a lack of border enforcement but a lack of ethno-cultural purity. It is an argument not about numbers but about identity. If European mainstream leaders accept immigration as an economic necessity or view diversity as compatible with the values of a liberal democracy, they are already in violation of Trump’s ideological demands.

European politics and society are built on the principles of non-discrimination. These principles have been under severe strain in recent years, but they are foundational. Trump’s rhetoric casts these principles as weaknesses. He praises Europe’s far right not because they propose workable migration strategies but because they champion cultural homogeneity and ethno-nationalism.

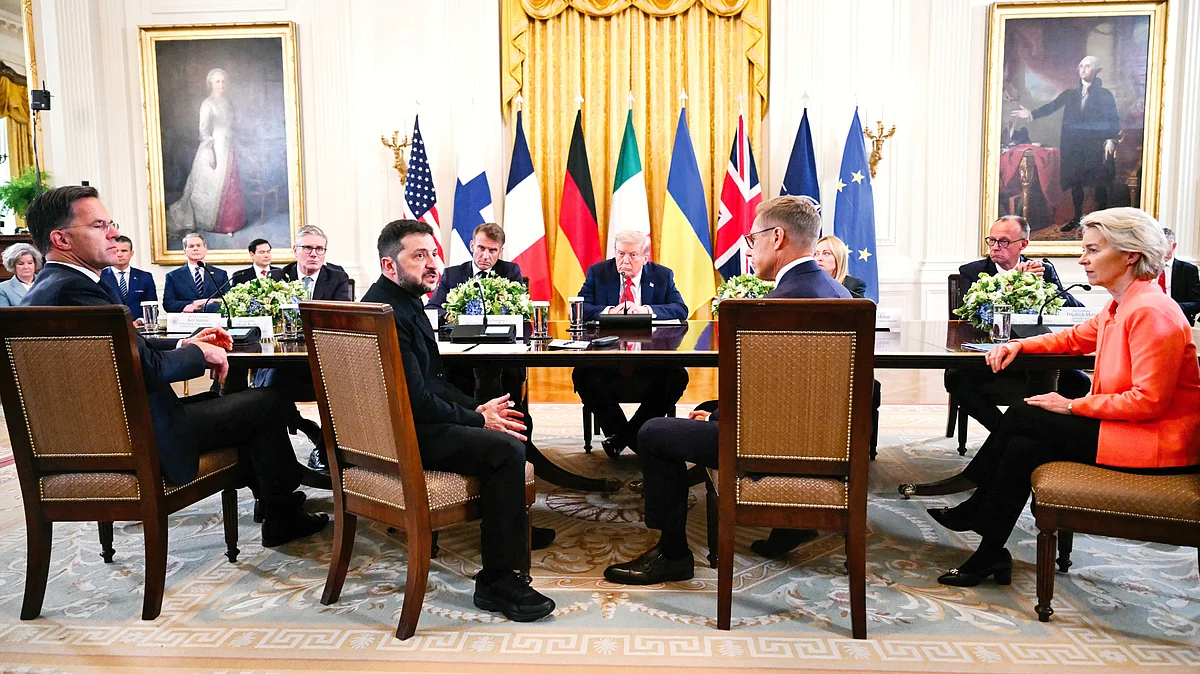

Ukraine reveals the same fault line. Europe sees Russia as a threat to its territorial integrity and frames it as a test of international law. Another matter that it has not shown the same fervour in defending international law in Gaza.

Trump, by contrast, sees European support for Ukraine as another example of European weakness and dependency. His strategy aims at re-establishing stability with Moscow, even if that requires pressuring Kyiv into concessions.

EU’s security model is built on cooperation, shared sovereignty and legal norms. Trump’s security ideals are shaped by zero-sum competition and national identity politics. These models are not easy companions. When European leaders say they want strategic autonomy, they mean a stronger Europe inside the transatlantic alliance. When Trump demands autonomy for Europe, he means defence without the United States and under political conditions aligned with American nationalist priorities.

The United States and Europe were once bound by not just a security alliance but also a shared belief in open societies and democratic resilience. Trump has replaced this with a politics that is inimical to diversity, sees partnerships as extra baggage and multilateralism as disloyalty. Europe can’t win this argument. Instead, it’ll be better served defending its own vision of security rooted in cooperation and legality.

Ashok Swain is a professor of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University, Sweden. More of his writing may be read here

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines